Vir linguosus non dirigitur super terram (VII:9)

6 Feb. 7 June. 7 Oct.

The ninth degree of humility is, that a monk refrain his tongue from speaking, keeping silence until a question be asked him, as the Scripture sheweth: “In much talking thou shalt not avoid sin”: and, “The talkative man shall not be directed upon the earth.”

Silence, obedience, and humility go together. Where one finds one of these virtues, one will find the other two. The man who talks much is rarely a good listener. The man who will not listen to God loses the ability to listen to others, and the man who will not listen to others loses the ability to listen to God.

Saint Benedict enjoins the practice of silence because he knows that in much speaking there will inevitably occur sins against charity, justice, purity, truth, and many other virtues. Saint Ambrose says:

Now what ought we to learn before everything else, but to be silent, that we may be able to speak? Lest my voice should condemn me, before that of another acquit me; for it is written:

By your words you shall be condemned.What need is there, then, that you should hasten to undergo the danger of condemnation by speaking, when you can be more safe by keeping silent? How many have I seen to fall into sin by speaking, but scarcely one by keeping silent; and so it is more difficult to know how to keep silent than how to speak. I know that most persons speak because they do not know how to keep silent. It is seldom that any one is silent even when speaking profits him nothing. He is wise, then, who knows how to keep silent. Lastly, the Wisdom of God said:The Lord has given to me the tongue of learning, that I should know when it is good to speak.Justly, then, is he wise who has received of the Lord to know when he ought to speak. Wherefore the Scripture says well:A wise man will keep silence until there is opportunity.(On the Duties of the Clergy, Chapter II:5)

Silence begins within oneself. There are men who keep up a ceaseless conversation with themselves. Their souls are polluted by the noise of their own vain chatter. Outwardly these men may appear to be quiet but, inwardly, they never stop talking. Their secret conversations are made up of criticisms, complaints, and comparisons. They indulge in detailed judgments of their brethren and in reveries of self–pity. Even when they go to prayer, they cannot pray because their interior noise keeps them from adoring in the silence of a listening heart.

There are also men who cannot let go of the past. They keep an interior archive of old recordings: negative and hurtful things said by parents, or siblings, or teachers, or employers, or colleagues. At the slightest provocation they replay old recordings and respond to them inwardly with fear, resentment, anger, sadness, and discouragement. One who is resolved to practice a true Benedictine silence must have the courage to get rid of his interior archive of old recordings. Such voices from the past impinge on the present and pollute the heart with a toxic noise. Saint Isaac the Syrian is representative of the whole monastic tradition when he says:

Many are avidly seeking but they alone find who remain in continual silence. Every man who delights in a multitude of words, even though he says admirable things, is empty within.

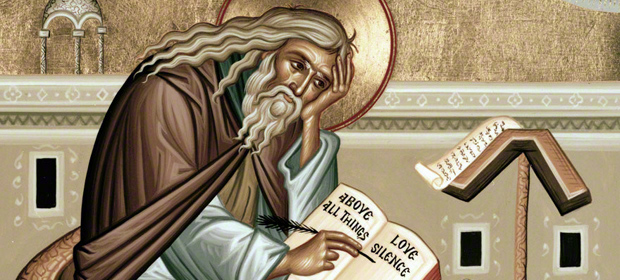

If you love truth be a lover of silence. Silence like the sunlight will illuminate you in God and deliver you from the phantoms of ignorance. Silence will unite you with God Himself. More than all things love silence, it brings you a fruit that tongue cannot describe.

In the beginning we have to force ourselves to be silent and then there is born something which draws us to silence. May God give you an experience of this something which is born of silence.

If only you will practice this, untold light will dawn upon you as a consequence. After a while a certain sweetness is born in the heart of this exercise and the body is drawn almost by force to remain in silence. (Ascetical Homily 64)

Benedictine silence, ultimately, is way of listening to God. It is a way of responding to the silence of the Host with the silence of adoration. Tacere et adorare: Be still and adore. Our Declarations are particularly compelling on the practice of a Eucharistic silence:

44. The silence of the Sacred Host must reign, not only over the hearts, minds,and lips of the monks, but over the entire monastery and its land, so as to foster an atmosphere of order and of peace conducive to ceaseless adoration.

45. By practicing silence at all times, the monks will avoid innumerable sins of the tongue and foster, both within themselves and within the monastery, an atmosphere that offers optimal resonance to the Word of God.

46. By assiduous contemplation and adoration of the Sacred Host, the monks will come to love the observance of silence by which it is given them to imitate the sacramental state of the Incarnate Word, Who, now in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, as once in His hidden life and bitter Passion, remains silent and still.