Mother Mectilde and Adoration, Part VI: A Charism Exhaled in Love

On the Feast of the Transitus of our holy father Benedict, we present the final section of our series of articles about how Mother Mectilde began the life of the Benedictines of the Perpetual Adoration. Click here for part I , here for part II, here for part III, and here for part IV and here for part V.

On the Feast of the Transitus of our holy father Benedict, we present the final section of our series of articles about how Mother Mectilde began the life of the Benedictines of the Perpetual Adoration. Click here for part I , here for part II, here for part III, and here for part IV and here for part V.

12 March, 1654

We wrote in the last part about the events of 12 March, 1654, which can be considered the beginning of the Institute of the Benedictines of Perpetual Adoration.

Peace had returned to the kingdom of France after the end in the previous year of civil war, known as the Fronde, which was fought between 1648-1653. Anne of Austria, the regent, in order to keep the vow that had been made to establish an institute of perpetual adoration, presided personally on 12 March at the opening of the cloister of the first Benedictines of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. On that day a cross was placed on the principal door of the cloister indicating that the new monastery in Rue Férou was canonically erected and that enclosure was officially established.

Queen Anne of Austria was invited to come before the monstrance. There she read an amende honorable of a beautiful Trinitarian design. She followed the custom of the day wherein condemned criminals would make an act of reparation for capital crimes against God or the King, observing to the same customs as the criminal would in his amende honorable. In essence she was, in the name of all her subjects, pleading guilty for the Eucharistic profanations committed during the previous war, and, in pleading guilty, she was offering the Eucharist reparation for all the offenses that had occurred.

The Charism

After the momentous ceremony of 12 March 1654, Mother Mectilde’s concern became to guide the unfolding of the way of life of the newly established monastery.

Mother Mectilde insisted on what, today, we would call the specific charism of the foundation, that is, the graced identity by which a particular community fulfills its unique mission in the Church. For Mother Mectilde, this graced identity found expression in a continuous presence of adoration and reparation before the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. The foundress was well aware of the sacrileges and abominations perpetrated against Our Lord in the Sacrament of His Love. She knew of the diabolical machinations of people involved in superstition, witchcraft, and magic, and of Sacred Hosts stolen and exchanged among the perfidious adherents of secret societies and cults. She suffered whenever the Most Holy Sacrament was treated with irreverence, ingratitude, indifference, and scorn. She grieved when priests offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass hastily and unworthily, with scant fervour, attention, and devotion. She suffered the ignominy endured by Our Lord when He descended sacramentally into those whose souls were chilled and darkened by grave sin.

Self-Emptying

The new Institute was brought into existence to offer Our Lord, present in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, souls that would enter into His own state of profound self-emptying (kenosis), souls that would enter into the humility, silence, obedience, and hiddenness of His sacramental state. The new Benedictines would carry out this imitation of the Eucharistic Jesus, the Deus absconditus (hidden God), by persevering in an unbroken watch of adoration and reparation by abiding, by day and by night, before His Face, close to His Heart.

Christus Passus

The life of the Benedictines of Perpetual Adoration was to be a participation in — and even a sort of identification with — Christ in the Eucharist. To abide for any length of time in faith, in hope, and in love, before the Most Blessed Sacrament draws one into the mysterious action of Jesus Christ, Priest and Victim. In the stillness of the tabernacle, or from the centre of the monstrance, He offers Himself to the Father with same dispositions that rose once from the altar of the Cross on Calvary. The Eucharistic Christ is the Christus passus: Christ sacramentally offered to the Father; Christ, the pure victim, the holy victim, the spotless victim, as described in the Roman Canon. Mother Mectilde saw those who were able to abide before Him in the Eucharist as becoming through, with, in, and for Him Eucharistic victims.

Language of Symbols

Mectilde be Bar had an understanding of the language of symbols, not after the fashion of contemporary anthropologists, but rather as a daughter of Church immersed in sacred signs and rites of the liturgy. She made use of symbols — such as those she made use of the daily Act of Reparation, the Amende Honorable — to express outwardly the mystical realities that, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, she had apprehended inwardly. Even as symbols give outward expression to what is essentially hidden, they engrave upon the souls of those who make use of them a vivid impression of what they signify. Fluency in this language of symbols has always been, and continues to be, integral to the pedagogy of monastic life.

The Monastic Observance of the Benedictines of Perpetual Adoration

In addition to the daily repetition of the Amende Honorable, Mother Mectilde established various usages to forward the life of adoration. She prescribed the hourly ringing of the bell five times as a way of recalling the community to mindfulness of the abiding presence of Our Lord in the Sacrament of His Love. The peal from the belfry was, in effect, an appeal to souls. She writes in her Constitutions:

To keep alive the memory of the inestimable benefit contained in the divine Eucharist, and to renew thanksgiving for it, one shall ring, at all the hours of the day and of the night, five strokes of the largest bell, whilst the one ringing as well as all those who hear it say: Praised and adored forever be the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar!

Perpetual Adoration

Mother Mectilde established that, hour after hour, a rota of adorers would assure a living, loving presence before the tabernacle. On Thursdays, the community would sing the Office and Mass of the Most Blessed Sacrament, and the Blessed Sacrament would be exposed in the monstrance from the end of Holy Mass until Compline, concluding with Benediction. Exposition so frequent as to even be weekly was extraordinary in the 17th Century, and she considered it a great privilege of the Institute.

In addition to every Thursday, there was also exposition on the feasts of Christmas, the Circumcision, the Epiphany, Easter, Pentecost, the Annunciation, the Assumption, Saint Benedict (on 21 March and on 11 July), and Saint Scholastica. On all the other days the perpetual adoration was carried out before the closed tabernacle.

Special Feasts

Certain days were to be solemnized, particularly Holy Thursday, Corpus Domini, the Thursday of Sexagesima (which is the feast of the Great Reparation), and January 1st, the Circumcision, seen as the inauguration of the victimhood of Christ. A renewal of the vows of monastic profession was to mark the first day of the New Year.

Our Lady

On 22 August 1654, the Blessed Virgin Mary was “elected” Abbess in perpetuity of the Institute. She was to be present in every corporate action of the community’s life. In all the regular places of the monastery, the image of the Mother of God occupied the place of honour. The Most Holy Virgin, insisted Mother Mectilde, would keep the community faithful to its charism. The practice of perpetual adoration, being entrusted into Our Lady’s hands, would remain vigorous, stable, and permanent. After God, Mother Mectilde turned to the Blessed Virgin Mary to preserve the monastery from falling into laxity, and to the insidious compromises that would weaken or alter its mission.

Saint Benedict and the Holy Rule

Saint Benedict and the Holy Rule

As for the Benedictine identity of the new monastery, it rested upon the rigorous observance of the Holy Rule that Mother Mectilde had first learned at Rambervillers, a community marked by the reform of Dom Didier de la Cour (1550 – 1623), founder of the Congregation of Saint Vanne and Saint Hydulphe. In Paris, the proximity of the monks of the Congregation of Saint Maur at Saint-Germain-des-Prés assured the new monastery of adorers a stable point of reference within the Benedictine tradition.

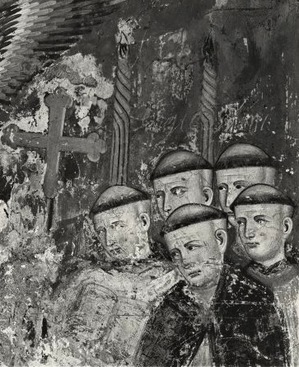

The Mystery of Saint Benedict’s Holy Death

The Benedictine identity of the Institute derived especially from Mother Mectilde’s mystical understanding of the death or transitus of the great Patriarch, as recounted by Pope Saint Gregory the Great in the Second Book of the Dialogues. Mother Mectilde writes:

Wanting to leave a testimony to the love that he nourished for the Most Holy Sacrament, [Saint Benedict] could not render It a greater honour, nor a more eloquent demonstration of his faith and of his charity, than by breathing his last in Its holy presence, and by entrusting the last beats of his heart to this adorable Host. . . so as to generate, in the time fixed by God, sons of his Order, who, until the end of the world, would render to [the Most Holy Sacrament] adoration, reverence, and the witness of uninterrupted love and reparation. Do you not see, my sisters, that Saint Benedict died standing up, so as to make us understand that, in a supreme act of love, he “exhaled” the sacred Institute to which we are professed? He conceived it in the Eucharist, so that, nearly twelve centuries later, it would come to birth.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)