What Are the Instruments of Good Works (IV:I)

CHAPTER IV. What Are the Instruments of Good Works

18 Jan. 19 May. 18 Sept.In the first place, to love the Lord God with all one’s heart, all one’s soul, and all one’s strength.

2. Then one’s neighbour as oneself.

3. Then not to kill.

4. Not to commit adultery.

5. Not to steal.

6. Not to covet.

7. Not to bear false witness.

8. To honour all men.

9. Not to do to another what one would not have done to oneself.

10. To deny oneself, in order to follow Christ.

11. To chastise the body.

12. Not to seek after delicate living.

13. To love fasting.

14. To relieve the poor.

15. To clothe the naked.

16. To visit the sick.

17. To bury the dead.

18. To help in affliction.

19. To console the sorrowing.

20. To keep aloof from worldly actions.

21. To prefer nothing to the love of Christ.

The sweet name of Christ appears twice in these first twenty–one instruments of good works: “To deny oneself, in order to follow Christ” and “To prefer nothing to the love of Christ”. Saint Benedict uses the name Christ rather than the Holy Name of Jesus, favoured by later saints and mystics. All the same, Walter Daniel, the twelfth century biographer of Saint Aelred Rievaulx, recounts that Saint Aelred’s last words were, “Festinate, for Crist luve”. Walter Daniel explains: “He spoke the Lord’s name in English, since he found it easier to utter, and in some way sweeter to hear in the language of his birth”.

Saint Benedict’s use of the name Christ reveals two things: first, that the words of the returning Christ ever resound in the ear of Saint Benedict’s heart: “I am Alpha and Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end” (Apocalypse 22:13). For Saint Benedict, as for the Apostle before him, “to live is Christ”. Mihi enim vivere Christus est (Philippians 1:21).

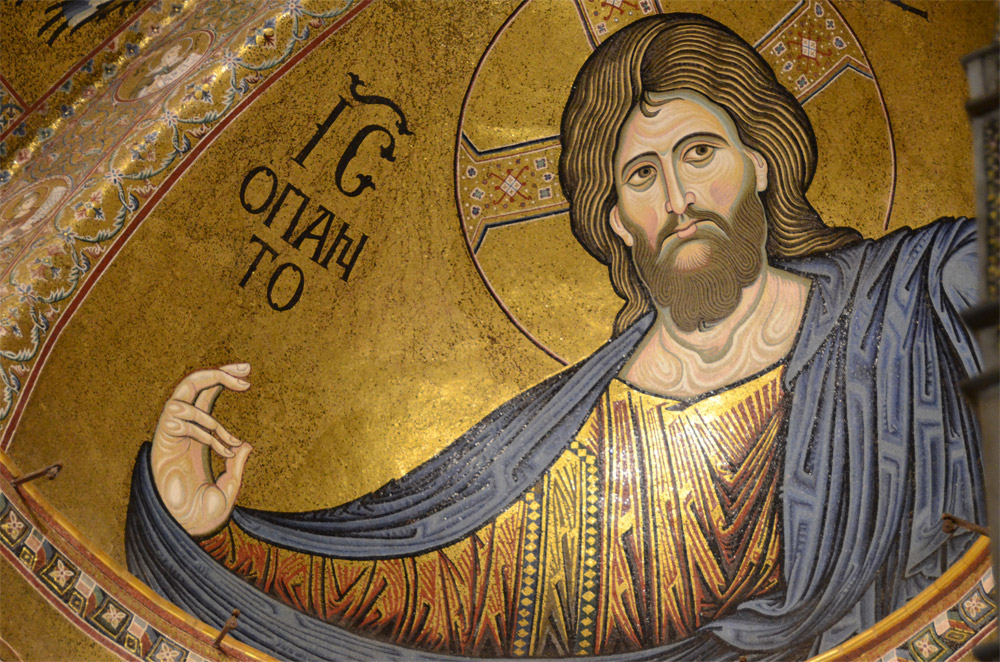

The second thing that Saint Benedict’s use of the name Christ reveals is that all his devotion derives from the immense, sober, breathtaking, glorious Christology of the great monuments of the liturgy: the Gloria in Excelsis Deo, the Te Deum Laudamus, the Te Decet Laus, and the Athanasian Creed, Quicumque Vult. Visually depicted, the Christology of Saint Benedict shines forth from the ancient iconography of the Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ, the All–Powerful Christ, or as Saint Benedict calls Him in the Prologue, “the Lord Christ, our true king”.

If you would grasp the Christology of Saint Benedict, and make it your own, meditate the Gloria in Excelsis Deo, the Te Deum Laudamus, the Te Decet Laus, and the Athanasian Creed, Quicumque Vult. Even more, open your eyes wide to contemplate the Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ depicted in the apses of so many ancient basilicas and cathedrals. I think always of Cefalù and Monreale in Sicily, but there are hundreds of other churches in which the glorious Face of Christ, full of majesty and mildness, shines from the sanctuary. This, of course, is intimately tied up with the inscription from the book of the prophet Daniel on our monastery’s coat of arms: Illumina faciem tuam super sanctuarium tuum, “Lift up the light of Thy countenance upon Thy sanctuary” (Daniel 9:17).

The vision of the Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ, full of majesty and dread, that fills the gaze of Saint Benedict does not, however, obscure, the vision of the humble Christ who, making Himself very close to men, says in the Prologue of the Holy Rule: “My eyes will be upon you, and My ears will be open to your prayers; and before you call upon Me, I will say unto you, Behold, I am here”. To these words of Christ, Saint Benedict adds, “What can be sweeter to us, dearest brethren, than this voice of the Lord inviting us? Behold in His loving-kindness the Lord sheweth unto us the way of life” (Prologue). Saint Benedict never loses sight of Him who says, “Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you. Take up my yoke upon you, and learn of me, because I am meek, and humble of heart: and you shall find rest to your souls. For my yoke is sweet and my burden light” (Matthew 11:28–30).

The Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar is where, here and now, we meet the the Χριστός Παντοκράτωρ, full of majesty and dread and the Christ of Extreme Humility, “the Lamb, which was slain from the beginning of the world” (Apocalypse 13:8). You know the magnificent hymn from the Liturgy of Saint James:

Let all mortal flesh keep silent, and stand with fear and trembling, and in itself consider nothing of earth; for the King of kings and Lord of lords cometh forth to be sacrificed, and given as food to the believers; and there go before Him the choirs of Angels, with every dominion and power, the many-eyed Cherubim and the six-winged Seraphim, covering their faces, and crying out the hymn: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

“Face to face”, says Saint Ambrose, “Thou hast made Thyself known to me, O Christ, for I have found Thee in Thy mysteries”. This liturgical contemplation of Christ leads to the encounter with Christ at every hour and in every place in the monastery. In the abbot, there is Christ; in the sick brother, Christ; in the young and in the old, Christ; in the pilgrim and in the guest, Christ; in one another and, especially, in the least among us, Christ. It is this comprehensive Christological vision that confers upon Benedictine life its wonderful unity. In modern times, the most eloquent proponent of this comprehensive Christological vision is Blessed Abbot Marmion, as set forth in his trilogy: Christ the Life of the Soul, Christ in His Mysteries, Christ the Ideal of the Monk. Always Christ.

Amor meus, pondus meum, said Saint Augustine, that is, “I go in the direction of my heart’s weight”. So it is with our father Saint Benedict. Everything in Saint Benedict goes towards Christ, gravitates to Christ. I pray that it may so with us who are his sons. “For where thy treasure is, there is thy heart also” (Matthew 6:21).