Saint Bede the Venerable

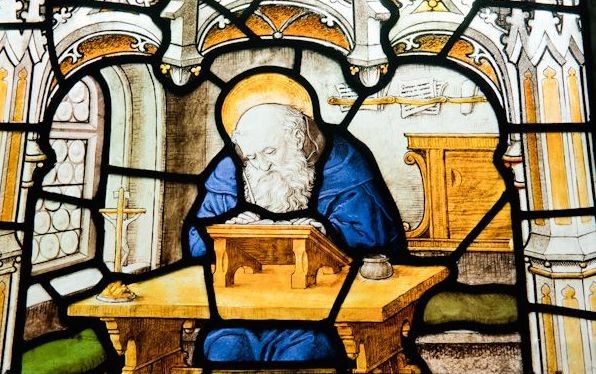

Today is the feast of Saint Bede the Venerable, a model for all Benedictine monks by reason of his serene fidelity to the regular observance, to liturgical prayer, and to study, all within the enclosure of the monastery. This stained glass window is a delightful depiction of Saint Bede: he is in his cell, seated at his desk. Before him, on his desk, there is a crucifix and, on a reading stand, the open book of the Scriptures. In both the crucifix and the Scriptures Saint Bede sees Christ; he contemplates Christ; he is absorbed by Christ. On the wall behind Saint Bede one sees various notes and letters arranged in a kind of filing system. Saint Bede’s cell is tidy and bright. On his desk there is nothing superfluous. A clear desk fosters a clear mind, making lectio divina easier. The expression on Saint Bede’s face reveals a profound humility of heart and a childlike purity. Characterized by “the love of learning and the desire for God”, Saint Bede remains a model of single–hearted devotion to Christ.

Pope Benedict XVI on Saint Bede the Venerable

Wednesday, 18 February 2009

Study, Observance, Singing

The Saint we are approaching today is called Bede and was born in the north-east of England, to be exact, Northumbria, in the year 672 or 673. He himself recounts that when he was seven years old his parents entrusted him to the Abbot of the neighbouring Benedictine monastery to be educated: “spending all the remaining time of my life a dweller in that monastery”. He recalls, “I wholly applied myself to the study of Scripture; and amidst the observance of the monastic Rule and the daily charge of singing in church, I always took delight in learning, or teaching, or writing” (Historia Eccl. Anglorum, v, 24). In fact, Bede became one of the most outstanding erudite figures of the early Middle Ages since he was able to avail himself of many precious manuscripts which his Abbots would bring him on their return from frequent journeys to the continent and to Rome. His teaching and the fame of his writings occasioned his friendships with many of the most important figures of his time who encouraged him to persevere in his work from which so many were to benefit.

Forever before Your Face

When Bede fell ill, he did not stop working, always preserving an inner joy that he expressed in prayer and song. He ended his most important work, the Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, with this invocation: “I beseech you, O good Jesus, that to the one to whom you have graciously granted sweetly to drink in the words of your knowledge, you will also vouchsafe in your loving kindness that he may one day come to you, the Fountain of all wisdom, and appear forever before your face”. Death took him on 26 May 737: it was the Ascension.

The One Word of God: Christ

Sacred Scripture was the constant source of Bede’s theological reflection. After a critical study of the text (a copy of the monumental Codex Amiatinus of the Vulgate on which Bede worked has come down to us), he comments on the Bible, interpreting it in a Christological key, that is, combining two things: on the one hand he listens to exactly what the text says, he really seeks to hear and understand the text itself; on the other, he is convinced that the key to understanding Sacred Scripture as the one word of God is Christ, and with Christ, in his light, one understands the Old and New Testaments as “one” Sacred Scripture. The events of the Old and New Testaments go together, they are the way to Christ, although expressed in different signs and institutions (this is what he calls the concordia sacramentorum).

The Church

For example, the tent of the covenant that Moses pitched in the desert and the first and second temple of Jerusalem are images of the Church, the new temple built on Christ and on the Apostles with living stones, held together by the love of the Spirit. And just as pagan peoples also contributed to building the ancient temple by making available valuable materials and the technical experience of their master builders, so too contributing to the construction of the Church there were apostles and teachers, not only from ancient Jewish, Greek and Latin lineage, but also from the new peoples, among whom Bede was pleased to list the Irish Celts and Anglo-Saxons. St Bede saw the growth of the universal dimension of the Church which is not restricted to one specific culture but is comprised of all the cultures of the world that must be open to Christ and find in him their goal.

The Historian

Another of Bede’s favourite topics is the history of the Church. After studying the period described in the Acts of the Apostles, he reviews the history of the Fathers and the Councils, convinced that the work of the Holy Spirit continues in history. In the Chronica Maiora, Bede outlines a chronology that was to become the basis of the universal Calendar “ab incarnatione Domini”. In his day, time was calculated from the foundation of the City of Rome. Realizing that the true reference point, the centre of history, is the Birth of Christ, Bede gave us this calendar that interprets history starting from the Incarnation of the Lord. Bede records the first six Ecumenical Councils and their developments, faithfully presenting Christian doctrine, both Mariological and soteriological, and denouncing the Monophysite and Monothelite, Iconoclastic and Neo-Pelagian heresies.

Lastly he compiled with documentary rigour and literary expertise the Ecclesiastical History of the English Peoples mentioned above, which earned him recognition as “the father of English historiography”. The characteristic features of the Church that Bede sought to emphasize are: a) catholicity, seen as faithfulness to tradition while remaining open to historical developments, and as the quest for unity in multiplicity, in historical and cultural diversity according to the directives Pope Gregory the Great had given to Augustine of Canterbury, the Apostle of England; b) apostolicity and Roman traditions: in this regard he deemed it of prime importance to convince all the Irish, Celtic and Pict Churches to have one celebration for Easter in accordance with the Roman calendar. The Computo, which he worked out scientifically to establish the exact date of the Easter celebration, hence the entire cycle of the liturgical year, became the reference text for the whole Catholic Church.

Teacher of Liturgical Theology

Bede was also an eminent teacher of liturgical theology. In his Homilies on the Gospels for Sundays and feast days he achieves a true mystagogy, teaching the faithful to celebrate the mysteries of the faith joyfully and to reproduce them coherently in life, while awaiting their full manifestation with the return of Christ, when, with our glorified bodies, we shall be admitted to the offertory procession in the eternal liturgy of God in Heaven. Following the “realism” of the catecheses of Cyril, Ambrose and Augustine, Bede teaches that the sacraments of Christian initiation make every faithful person “not only a Christian but Christ”. Indeed, every time that a faithful soul lovingly accepts and preserves the Word of God, in imitation of Mary, he conceives and generates Christ anew. And every time that a group of neophytes receives the Easter sacraments the Church “reproduces herself” or, to use a more daring term, the Church becomes “Mother of God”, participating in the generation of her children through the action of the Holy Spirit.

Messages for Various States of Life

By his way of creating theology, interweaving the Bible, liturgy and history, Bede has a timely message for the different “states of life”: a) for scholars (doctores ac doctrices) he recalls two essential tasks: to examine the marvels of the word of God in order to present them in an attractive form to the faithful; to explain the dogmatic truths, avoiding heretical complications and keeping to “Catholic simplicity”, with the attitude of the lowly and humble to whom God is pleased to reveal the mysteries of the Kingdom; b) pastors, for their part, must give priority to preaching, not only through verbal or hagiographic language but also by giving importance to icons, processions and pilgrimages. Bede recommends that they use the Vulgate as he himself does, explaining the “Our Father” and the “Creed” in Northumbrian and continuing, until the last day of his life, his commentary on the Gospel of John in the vulgate; c) Bede recommends to consecrated people who devote themselves to the Divine Office, living in the joy of fraternal communion and progressing in the spiritual life by means of ascesis and contemplation that they attend to the apostolate no one possesses the Gospel for himself alone but must perceive it as a gift for others too both by collaborating with Bishops in pastoral activities of various kinds for the young Christian communities and by offering themselves for the evangelizing mission among the pagans, outside their own country, as “peregrini pro amore Dei”.

A Hard–Working Church

Making this viewpoint his own, in his commentary on the Song of Songs Bede presents the Synagogue and the Church as collaborators in the dissemination of God’s word. Christ the Bridegroom wants a hard-working Church, “weathered by the efforts of evangelization” there is a clear reference to the word in the Song of Songs (1: 5), where the bride says “Nigra sum sed formosa” (“I am very dark, but comely”) intent on tilling other fields or vineyards and in establishing among the new peoples “not a temporary hut but a permanent dwelling place”, in other words, intent on integrating the Gospel into their social fabric and cultural institutions.

The Domestic Church

In this perspective the holy Doctor urges lay faithful to be diligent in religious instruction, imitating those “insatiable crowds of the Gospel who did not even allow the Apostles time to take a mouthful”. He teaches them how to pray ceaselessly, “reproducing in life what they celebrate in the liturgy”, offering all their actions as a spiritual sacrifice in union with Christ. He explains to parents that in their small domestic circle too they can exercise “the priestly office as pastors and guides”, giving their children a Christian upbringing. He also affirms that he knows many of the faithful (men and women, married and single) “capable of irreproachable conduct who, if appropriately guided, will be able every day to receive Eucharistic communion” (Epist. ad Ecgberctum, ed. Plummer, p. 419).

Bede: A Builder of Christian Europe

The fame of holiness and wisdom that Bede already enjoyed in his lifetime, earned him the title of “Venerable”. Pope Sergius I called him this when he wrote to his Abbot in 701 asking him to allow him to come to Rome temporarily to give advice on matters of universal interest. After his death, Bede’s writings were widely disseminated in his homeland and on the European continent. Bishop St Boniface, the great missionary of Germany, (d. 754), asked the Archbishop of York and the Abbot of Wearmouth several times to have some of his works transcribed and sent to him so that he and his companions might also enjoy the spiritual light that shone from them. A century later, Notker Balbulus, Abbot of Sankt Gallen (d. 912), noting the extraordinary influence of Bede, compared him to a new sun that God had caused to rise, not in the East but in the West, to illuminate the world. Apart from the rhetorical emphasis, it is a fact that with his works Bede made an effective contribution to building a Christian Europe in which the various peoples and cultures amalgamated with one another, thereby giving them a single physiognomy, inspired by the Christian faith. Let us pray that today too there may be figures of Bede’s stature, to keep the whole continent united; let us pray that we may all be willing to rediscover our common roots, in order to be builders of a profoundly human and authentically Christian Europe.