Confirmetur in eo caritas

Chapter

Chapter

This morning at Chapter (a daily reflection on a chapter of the Rule of Saint Benedict) we read one of my favourite passages: “That the Abbot Be Solicitous for the Excommunicated” (Chapter XXVII).

Let the Abbot show all care and concern towards erring brethren because “they that are in health need not a physician, but they that are sick” (Mt 9:12). Therefore, like a wise physician he ought to use every opportunity to send consolers, namely, wise elderly brethren, to comfort the troubled brother, as it were, in secret, and induce him to make humble satisfaction; and let them console him “lest he be swallowed up with overmuch sorrow” (2 Cor 2:7); but, as the same Apostle saith, “let your charity towards him be strengthened” (2 Cor 2:8); and let everyone pray for him.

The Excommunicated Brother

First of all, what does Saint Benedict mean by “an excommunicated brother”? Saint Benedict so cherishes life together that he can think of no better corrective measure than depriving a brother, in whole or in part, of participation in the daily round of community activities and, in particular, of meals and of the solemn choral prayer. One might think of it as an adult version of the very effective “time out” that my brother, the father of three, uses with his sometimes obstreperous children.

Toward Repentance and Healing

Saint Benedict is not so much concerned with punishing offences as he is with bringing the offending brother to repentance and to healing. The measures prescribed in the so called “penal code” of the Holy Rule are medicinal and therapeutic, not punitive. Saint Benedict presents them as remedies for the variety of spiritual infirmities that can and do affect even the most fervent monastic communities.

Sapiens Medicus

The brothers in question are not iniquitous criminals; they are weak men who have fallen short of the ideal, frail sinners who keep on missing the mark, even after repeated admonitions and interventions. The first biblical passage that Saint Benedict quotes in this chapter is Matthew 9:12: “They that are in health need not a physician, but they that are ill.” He describes the abbot (the father of the monastery) as a sapiens medicus, wise physician. He would have him use “every remedy in his power” to restore an ailing brother to spiritual health.

Salutary Intervention

In my own long experience of religious life, I have, more than once, witnessed situations in which a brother gave clear signs of delinquency; in which there was evidence of patterns of unhealthy and perhaps sinful behaviour; in which a brother by “acting out” was, in fact, crying out for help. Also, more than once, I have witnessed superiors turn a blind eye to the problem, refusing to intervene, even in cases where a wise and compassionate intervention could have brought about a real conversion of life and avoided scandal.

I know of one instance in which a student brother residing in a community other than his own was giving unmistakable signs of moral distress, unhealthy personal choices, and depression. The brother in question kept strange hours, failed to participate in community prayer and meals, and avoided the companionship of the religious residing in the same house. Although the superior of the host community had no canonical authority over this brother (who belonged to another religious Order), he certainly had an evangelical obligation to offer him the ministrations of mercy and of healing. Instead, like the priest and the levite of the parable of the Good Samaritan, the superior passed the brother by; he never sought out the brother for a personal conversation, and never attempted to intervene in a situation that had become a question to many. At the very least, he could have approached the brother in difficulty as a priest to a brother priest and said, “I sense — or I know — that you are in difficulty, brother. How can I help?”

Over a decade later, this same superior, denounced the brother whom he had virtually ignored in the throes of a grave spiritual and emotional crisis. He destroyed the brother’s reputation, causing untold anguish and grief. All of this happened long after the brother had recognized the error of his ways, sincerely repented, and begun to strive for holiness of life and emotional health. The superior, although a son of the Seraphic Father Saint Francis, would have done well to take a lesson from the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Over a decade later, this same superior, denounced the brother whom he had virtually ignored in the throes of a grave spiritual and emotional crisis. He destroyed the brother’s reputation, causing untold anguish and grief. All of this happened long after the brother had recognized the error of his ways, sincerely repented, and begun to strive for holiness of life and emotional health. The superior, although a son of the Seraphic Father Saint Francis, would have done well to take a lesson from the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Consolers

Even when Saint Benedict is obliged to separate a wayward monk from the rest of the community to give him time to reflect, and also to prevent the spread of his spiritual malady to others, the wise abbot sends trustworthy elders to “secretly comfort the troubled brother, to induce him to make humble satisfaction, and to console him lest he be swallowed up with overmuch sorrow.” Here one sees the magnanimity and resourcefulness of Saint Benedict; the abbot shares the duties of his spiritual paternity with chosen elders in the community. They are, as it were, the envoys of his mercy and paternal tenderness.

Charity and Prayer

When a brother shows signs of spiritual distress by disobedience, possessiveness, disregard for the Rule, or aggressive behaviour, that brother should not be judged, condemned, and forsaken. “Let charity be strengthened toward him,” says Saint Benedict. The remedy is more love, not less. And, he adds, “let everyone pray for him.” Charity and prayer can melt even the most hardened hearts, provided that those loving and praying, persevere and not lose heart.

The Care of Weakly Souls

The next section of Chapter XXVII reveals the Heart of Jesus living in the heart of Saint Benedict:

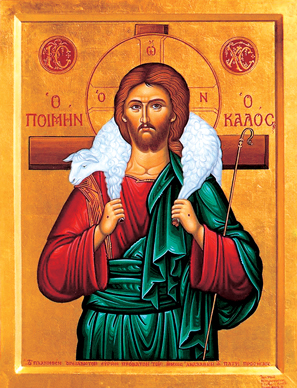

For the Abbot is bound to use the greatest solicitude, and to strive with all prudence and diligence, that none of the flock entrusted to him perish. For the Abbot must know that he has taken upon himself the care of weakly souls, not a tyranny over the strong; and let him fear the threat of the Prophet wherein God saith: “What ye saw to be fat, that ye took to yourselves, and what was diseased you threw away” (Ezek 34:3-4). And let him follow the tender example of the Good Shepherd, who, leaving the ninety-nine sheep on the mountains, went to seek the one that had gone astray, on whose weakness He had such pity, that He was pleased to place it on His sacred shoulders and thus carry it back to the fold (cf Lk 15:5).

Paternal Solicitude

In dealing with the wayward sheep of his flock, the abbot is to manifest the greatest solicitude, that is, an almost maternal devotedness. For an abbot after the heart of Saint Benedict there can be no greater tragedy than the loss of a brother. I am reminded of the words of the Apostle Saint Paul: “I speak the truth in Christ, I lie not, my conscience bearing me witness in the Holy Ghost, that I have great sadness, and continual sorrow in my heart. For I wished myself to be anathema from Christ, for my brethren. . . .” (Rom 9:1-2).

Father and Physician of Souls

The abbot is above all a father and a physician of souls. He is entrusted with the care of those bearing the burden of moral infirmities, and of weaknesses of soul and body. The abbot is not a tyrant driving the strong with threats and inspiring fear; he is a shepherd tending the flock with love and inspiring confidence. Saint Benedict warns the abbot of the sin of preferring “the fat” — the gifted, the charming, the virtuous, the intelligent, and the comely — and of throwing away “the diseased” — the not-so-gifted, the trying, those caught in webs of vice, the unintelligent, and the unattractive.

The Lost Sheep

Saint Benedict enjoins the abbot to follow the tender example of Jesus, the Good Shepherd, who leaves the ninety-nine well-behaved and observant sheep, so as to search for the one who, deceived by the world, the flesh, and the devil, has lost his way in the mists of temptation. If that one sheep cannot walk, the abbot is bound to carry him on his shoulders and, perhaps, to keep him by his side until, at length, he recovers health and begins to give signs of newness of life.

Not Just for Monks

In reflecting on this chapter of the Holy Rule, it occurred to me that it could just as well apply to bishops and to their priests as to abbots and their monks. It might even apply to fathers and to their children. At the end of Chapter every morning I pray, “Stir Thou up, O Lord, in our hearts, the Spirit to whom our holy father Saint Benedict was obedient, that filled with tht same Spirit, we might love what he loved and put into practice what he taught. Through Christ our Lord.” Would that all priests had a share in the spirit of the Holy Patriarch of Monks: self-sacrificing love, mercy, wisdom, patience, and zeal for souls.

I agree, Father Mark… the cruelest thing a Christian can do to a brother or sister in Christ is to ignore their sin and suffering… Years ago, I was so impressed when a pastor and several elders confronted a man in our church who was having an affair…they did it out of love for this man and his wife and family and the other person. It takes a lot of courage and love to speak to someone about their sin — no one wants to “interfere”, myself included. Spiritual leaders have a responsibility to the household of faith to seek out the erring sheep and the lost sheep as well as those sheep still to be brought into the fold. Peace, Taina

I have a “Rule” of St. Benedict and when I first read that part you just quoted it gave me such a sense of peace. It is the right thing to do. I was glad to read it because there is a very personal reason I needed to read those exact words. It has to do with my Spiritual Motherhood. I’m glad St. Benedict felt that way because I think it’s exactly how Jesus treats all of us. Lovingly.