Servant of the Servants of the Cross of Christ

Pope Benedict XVI on Saint Peter Damian

The Holy Father’s audience yesterday (September 2009) on Saint Peter Damian (1007-1072) revealed him, once again, as a Master of the Monastic Life! Pope Benedict XVI is unique in his grasp of the principles of the monastic way and in his application of them to the life of all who seek holiness, even outside the cloister. It is not uncommon to hear him say as he did yesterday, “This is also important for us today, even though we are not monks. . . .” Those of you who missed the Holy Father’s teaching in 2008 on his patron, Saint Benedict, will find it here.

Dear brothers and sisters,

Lover of Solitude and Intrepid Man of the Church

During these Wednesday catecheses, I have been discussing some of the great figures of the life of the Church since its origin. Today I would like to reflect on one of the most significant personalities of the 11th century, St. Peter Damian, monk, lover of solitude and, at the same time, intrepid man of the Church, personally involved in the work of reform undertaken by the popes of the time.

Gifted Writer

He was born in Ravenna in 1007 of a noble but poor family. He was orphaned, and lived a childhood of hardships and sufferings. Even though his sister Roselinda was determined to be a mother to him and his older brother, he was adopted as a son by Damian. In fact, because of this, he would later be called Peter of Damiano, Peter Damian. His formation was imparted to him first at Faenza and then at Parma, where, already at the age of 25, we find him dedicated to teaching. In addition to keen competence in the field of law, he acquired a refined expertise in the art of writing — “ars scribendi” — and, thanks to his knowledge of the great Latin classics, became “one of the best Latinists of his time, one of the greatest writers of the Latin Medieval Age” (J. Leclercq, Pierre Damien, Ermite et Homme d’Eglise, Rome, 1960, p. 172).

Sensitivity to Beauty

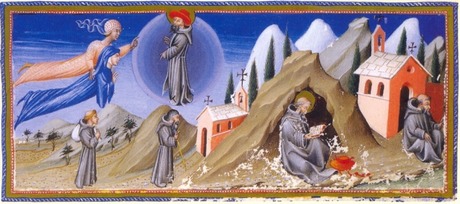

He distinguished himself in the most diverse literary genres: from letters to sermons, from hagiographies to prayers, from poems to epigrams. His sensitivity to beauty led him to a poetic contemplation of the world. Peter Damian conceived the universe as an inexhaustible “parable” and an extension of symbols, from which it is possible to interpret the interior life and the divine and supernatural reality. From this perspective, around the year 1034, the contemplation of God’s absoluteness compelled him to distance himself progressively from the world and its ephemeral realities, to withdraw to the monastery of Fonte Avellana, founded a few decades earlier, but already famous for its austerity. He wrote the life of the founder, St. Romuald of Ravenna, for the edification of the monks and, at the same time, dedicated himself to furthering his spirituality, expressing his ideal of eremitical monasticism.

Love of the Cross

A particularity must now be stressed: the hermitage of Fonte Avellana was dedicated to the Holy Cross, and the cross would be the Christian mystery that most fascinated Peter Damian. “He does not love Christ who does not love the cross of Christ,” he said (Sermo XVIII, 11, p. 117) and he calls himself: “Petrus crucis Christi servorum famulus” — Peter servant of the servants of the cross of Christ (Ep, 9, 1). Peter Damian addressed most beautiful prayers to the cross, in which he reveals a vision of this mystery that has cosmic dimensions, because it embraces the whole history of salvation: “O blessed cross,” he exclaimed, “you are venerated in the faith of patriarchs, the predictions of prophets, the assembly of the apostles, the victorious army of the martyrs and the multitudes of all the saints” (Sermo XLVIII, 14, p. 304).

Dear brothers and sisters, may the example of Peter Damian lead us also to always look at the cross as the supreme act of love of God for man, which has given us salvation.

The Salon Where God Converses With Men

For the development of the eremitical life, this great monk wrote a Rule which strongly stresses the “rigor of the hermitage”: In the silence of the cloister, the monk is called to live a life of daily and nocturnal prayer, with prolonged and austere fasts; he must exercise himself in generous fraternal charity and in an obedience to the prior that is always willing and available. In the study and daily meditation of sacred Scripture, Peter Damian discovered the mystical meaning of the Word of God, finding in it food for his spiritual life. In this connection, he called the cell of the hermitage the “salon where God converses with men.” For him, the eremitical life was the summit of Christian life; it was “at the summit of the states of life,” because the monk, free from the attachments of the world and from his own self, receives “the pledge of the Holy Spirit and his soul is happily united to the heavenly Spouse” (Ep 18, 17; cf. Ep 28, 43 ff.). This is also important for us today, even though we are not monks: To be able to be silent in ourselves to hear the voice of God, to seek, so to speak, a “salon” where God speaks to us: To learn the Word of God in prayer and meditation is the path for life.

Christ at the Center of the Monk’s Life

St. Peter Damian, who basically was a man of prayer, meditation and contemplation, was also a fine theologian: His reflection on several doctrinal subjects led him to important conclusions for life. Thus, for example, he expresses with clarity and vivacity the Trinitarian doctrine. He already used, in keeping with biblical and patristic texts, the three fundamental terms that later became determinant also for the West’s philosophy: processio, relatio e persona (cf. Opusc. XXXVIII: PL CXLV, 633-642; and Opusc. II and III: ibid., 41 ff. and 58 ff.). However, as theological analysis led him to contemplate the intimate life of God and the dialogue of ineffable love between the three divine Persons, he draws from it ascetic conclusions for life in community and for the proper relations between Latin and Greek Christians, divided on this topic. Also meditation on the figure of Christ has significant practical reflections, as the whole of Scripture is centered on him. The “Jewish people themselves,” notes St. Peter Damian, “through the pages of sacred Scripture, have, one could say, carried Christ on their shoulders” (Sermo XL VI, 15). Therefore Christ, he adds, must be at the center of the monk’s life: “Christ must be heard in our language, Christ must be seen in our life, he must be perceived in our heart” (Sermo VIII, 5). Profound union with Christ should involve not only monks but all the baptized. It also implies for us an intense call not to allow ourselves to be totally absorbed by the activities, problems and preoccupations of every day, forgetting that Jesus must truly be at the center of our life.

The Reformer of the Church

Communion with Christ creates unity among Christians. In Letter 28, which is a brilliant treatise of ecclesiology, Peter Damian develops a theology of the Church as communion. “The Church of Christ,” he wrote, “is united by the bond of charity to the point that, as she is one in many members, she is also totally gathered mystically in just one of her members; so that the whole universal Church is rightly called the only Bride of Christ in singular, and every chosen soul, because of the sacramental mystery, is fully considered Church.” This is important: not only that the whole universal Church is united, but that in each one of us the Church in her totality should be present. Thus the service of the individual becomes “expression of universality” (Ep 28, 9-23). Yet the ideal image of the “holy Church” illustrated by Peter Damian does not correspond — he knew it well — to the reality of his time. That is why he was not afraid to denounce the corruption existing in monasteries and among the clergy, above all due to the practice of secular authorities conferring the investiture of ecclesiastical offices: Several bishops and abbots behaved as governors of their own subjects more than as pastors of souls. It is no accident that their moral life left much to be desired. Because of this, with great sorrow and sadness, in 1057 Peter Damian left the monastery and accepted, though with difficulty, the appointment of cardinal bishop of Ostia, thus entering fully in collaboration with the popes in the difficult undertaking of the reform of the Church. He saw that it was not enough to contemplate, and had to give up the beauty of contemplation to assist in the work of renewal of the Church. Thus he renounced the beauty of the hermitage and courageously undertook numerous journeys and missions.

The Peacemaker

Because of his love of monastic life, 10 years later, in 1067, he was given permission to return to Fonte Avellana, resigning from the Diocese of Ostia. However, the desired tranquility did not last long: Two years later he was sent to Frankfurt in an attempt to prevent Henry IV’s divorce from his wife, Bertha; and again two years later, in 1071, he went to Montecassino for the consecration of the abbey’s church, and, at the beginning of 1072 he went to Ravenna to establish peace with the local archbishop, who had supported the anti-pope, causing the interdict on the city. During his return journey to the hermitage, a sudden illness obliged him to stay in Faenza in the Benedictine monastery of “Santa Maria Vecchia fuori porta,” where he died on the night of Feb. 22-23, 1072.

A Monk to the End

Dear brothers and sisters, it is a great grace that in the life of the Church the Lord raised such an exuberant, rich and complex personality as that of St. Peter Damian and it is not common to find such acute and lively works of theology as those of the hermit of Fonte Avellana. He was a monk to the end, with forms of austerity that today might seem to us almost excessive. In this way, however, he made of monastic life an eloquent testimony of the primacy of God and a call to all to walk toward holiness, free from any compromise with evil. He consumed himself, with lucid consistency and great severity, for the reform of the Church of his time. He gave all his spiritual and physical energies to Christ and the Church, always remaining, as he liked to call himself, “Petrus ultimus monachorum servus,” Peter, last servant of the monks.