Blessed Schuster’s Daily Thoughts on the Rule: Palm Sunday

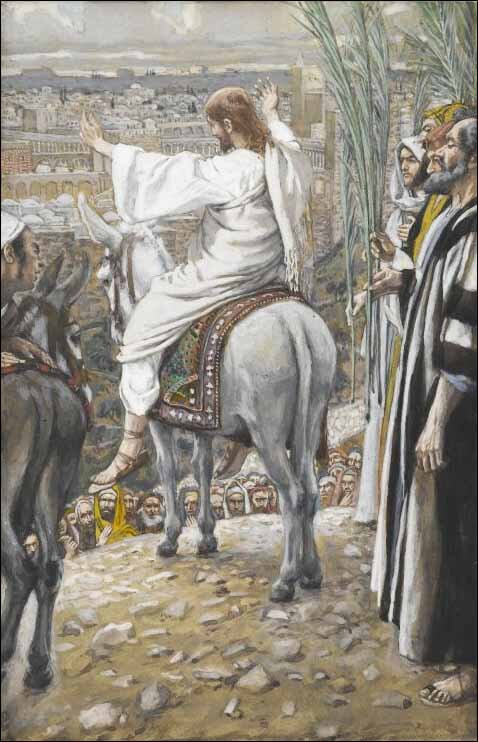

Palm Sunday

Station at St John Lateran

The Christian Pasch

1. The Station is in the Lateran, where today the rites of the Paschal Week are begun. The Mass is preceded by the stational procession, the blessing of olive or palm branches, with the reading of the Gospel of Saint Matthew where the Lord’s entry into the Holy City is described.

***

That she-ass with the colt tied to a gate of the village of Bethphage symbolises the entire human race in its two sexes, once expelled from the City of God through the sins of the First Parents.

The Saviour finally comes to loosen it from the ancient fault through the ministry of the Apostles. At His command, they go through all the world, and lead souls back to the Divine Master, because omnes gentes servient ei. (Ps. 71: ‘All nations shall serve Him.’)

The procession is ordered, arranged, and begun; it moves to the Church militant and reaches even to the Church triumphant which is in Heaven.

The Divine Crucified One goes before; there follow the Apostles, the Martyrs, the Saints. During the procession all pray and sing praise to God: Hosanna in excelsis.

Saint Benedict alludes to this type of procession when in the epilogue of the Holy Rule, after having recalled the Sacred Authors of the Bible, he commemorates the great Doctors of the Catholic Church, St Basil, the Fathers of Egypt and Palestine, Cassian and the throng bene viventium et oboedientium monachorum (Rule Ch. 73: ‘of observant and obedient monks’).

***

2. The procession moves towards Jerusalem:

It proceeds in an ordered way, each occupying the post assigned to him by the divine disposition. For this reason Saint Benedict writes: ‘Each has from God his own gift, one in one manner, one in another.’ (Rule, Ch. 40)

The Holy Patriarch attributes a great importance also to external order. This should govern the liturgical life in a Benedictine monastery where the regular observance flourishes. Ordines suos in monasterio observent. (Rule, Ch. 63: ‘Let them keep their proper place in the community.’)

The palm or olive branches which the participants in the procession bear in hand symbolise the religious virtues, the victories over the passions, and the exercise of the works of mercy, of which a monk’s day in a Benedictine abbey are woven.

Monachus est Angelus et opus eius misericordia, pax et sacrificium laudis (‘The monk is an Angel, and his ministry is mercy, peace and the sacrifice of praise’): thus did Saint Nilus of Rossano define the Benedictine monk.

In procession, there is prayer and there is singing.

He who, for love of God, observes the Rule patiently: that one proceeds in the procession praying. He who instead, is pushed forward by divine love: that one sings, because cantare amantis est [singing belongs to the lover], as Saint Augustine says.

***

3. For the procession the Saviour has need of the young ass, on which the Apostles respectfully spread their cloaks for Him to sit there.

3. For the procession the Saviour has need of the young ass, on which the Apostles respectfully spread their cloaks for Him to sit there.

Saint Benedict comments that this young ass symbolises precisely the humble monk:

‘The sixth degree of humility is, when the monk is content with everything vile and cast off, and before whatever is commanded him, shall consider himself always as a bad and unworthy workman, saying within himself with the Prophet: I have been reduced to nothing and I knew it not. In Thy presence, I am become like a beast of burden, but still I am always with Thee.’ (Rule, Ch. 7)

Nonetheless, the young ass of the monastery should take comfort: he bears the One Who bears all!

So that his service may prove truly useful, however, he must let himself be guided at the bridle by the Apostles, that is by Ecclesiastical Authority. It is necessary that the abbot spread over the lively colt his wooly mantle.1 Obedience will sanctify that servitium sanctum quod professi sunt. (Rule, Ch. 5: ‘For the sake of the holy profession which they have pronounced.’)

How long will this last?

Et confestim dimittet eos. (Matt 21:3: ‘And at once he will let them go.’) The Gospel promise is explicit.

Our entire life is equivalent to this brief confestim [at once], which now seems as if it will never pass. In eternity, however, we will see with Paul the momentaneum et leve tribulationis nostrae (2 Cor 4:17: ‘Our tribulations, light and of an instant’), and how rightly is it called: confestim.

1 The term used here is melote, the term used in the by Saint Gregory in his life of Saint Benedict to describe the mantle worn by the saint.

↩