Reprove, entreat, rebuke (II:5)

13 Jan. 14 May. 13 Sept.

For the Abbot in his doctrine ought always to observe the bidding of the Apostle, wherein he says: “Reprove, entreat, rebuke”; mingling, as occasions may require, gentleness with severity; shewing now the rigour of a master, now the loving affection of a father, so as sternly to rebuke the undisciplined and restless, and to exhort the obedient, mild, and patient to advance in virtue. And such as are negligent and haughty we charge him to reprove and correct. Let him not shut his eyes to the faults of offenders; but as soon as they appear, let him strive with all his might to root them out, remembering the fate of Heli, the priest of Silo. Those of good disposition and understanding let him, for the first or second time, correct only with words; but such as are froward and hard of heart, and proud, or disobedient, let him chastise with bodily stripes at the very first offence, knowing that it is written: “The fool is not corrected with words.” And again “Strike thy son with the rod, and thou shalt deliver his soul from death.”

In the school of the Lord’s service that is the monastery, the abbot is the doctor inasmuch as he offers a doctrine. The abbot is bound to rebuke the undisciplined and restless, and to exhort the obedient, mild, and patient to advance in virtue. He can, in some way, do both by nourishing his whole flock — the undisciplined, the restless, the obedient, the mild, and the patient — with consistently wholesome teaching in imitation of Christ, the Good Shepherd:

This is what the Lord God says: I mean to go looking for this flock of mine, search it out for myself. As a shepherd, when he finds his flock scattered all about him, goes looking for his sheep, so will I go looking for these sheep of mine, rescue them from all the nooks into which they have strayed when the dark mist fell upon them. Rescued from every kingdom, recovered from every land, I will bring them back to their own country; they shall have pasture on the hill-sides of Israel, by its watercourses, in the resting-places of their home. Yes, I will lead them out into fair pastures, the high mountains of Israel shall be their feeding-ground, the mountains of Israel, with soft grass for them to rest on, rich feed for them to graze. Food and rest, says the Lord God, both these I will give to my flock. The lost sheep I will find, the strayed sheep I will bring home again; bind up the broken limb, nourish the wasted frame, keep the well-fed and the sturdy free from harm; they shall have a true shepherd at last. (Ezechiel 34:11–16)

The abbot must, therefore,” says Saint Benedict, “be learned in the Law of God, that he may know whence to bring forth new things and old” (Chapter LXIV). The abbot does this principally by means of the daily Chapter on the Holy Rule — an indispensable element of our observance — and by preaching. He also does it by attending to the development of the monastic library; by directing the reading of his monks; by fostering the love of letters (that is, of sacred learning) among those of his monks who are capable of intellectual work; and by orienting the learning of all his monks to an unflagging desire for God, to their union with God by means of the theological virtues; to humble adoration; and to the praise of God in the Opus Dei. I find, in the Epistles of Saint Paul to Timothy, a program for every abbot:

Reading, preaching, instruction, let these be thy constant care while I am absent. A special grace has been entrusted to thee; prophecy awarded it, and the imposition of the presbyters’ hands went with it; do not let it suffer from neglect. Let this be thy study, these thy employments, so that all may see how well thou doest. Two things claim thy attention, thyself and the teaching of the faith; spend thy care on them; so wilt thou and those who listen to thee achieve salvation. (1 Timothy 4:13–16)

Preach the word, dwelling upon it continually, welcome or unwelcome; bring home wrong-doing, comfort the waverer, rebuke the sinner, with all the patience of a teacher. The time will surely come, when men will grow tired of sound doctrine, always itching to hear something fresh; and so they will provide themselves with a continuous succession of new teachers, as the whim takes them, turning a deaf ear to the truth, bestowing their attention on fables instead. It is for thee to be on the watch, to accept every hardship, to employ thyself in preaching the gospel, and perform every duty of thy office, keeping a sober mind. (2 Timothy 4:2–5)

There are two dangers related to the “love of learning,” both of which can precipitate the decline of a monastery, and the loss of the “good zeal” of which Saint Benedict treats in Chapter LXXII. The first danger presents itself when an abbot neglects the duty of teaching, dispenses with the daily Chapter and from preaching, has little care for the monastic library, and allows his monks to settle into a kind of intellectual lethargy. The second danger presents itself when the abbot allows the love of learning to be divorced from prayer; when he does not order all learning in the monastery to the Opus Dei; and when, seeing that a monk’s intellectual pursuits are not leading him to humble adoration, fails to intervene, and so becomes party to that monk’s loss of what, in the first place, drives all Benedictine life: Quaerere Deum.

I have seen monasteries fall into decline and wither away because sound teaching, disciplined reading, and the care of the monastic library, came to be neglected. A vapid and sentimental piety will not sustain a man on the monastic journey. Disciplined reading, assiduous lectio divina, and the love of sound doctrine, ordered to the all–surpassing knowledge of Jesus Christ and to the contemplation of the splendour of the truth, sustain a man in the love of God and increase in him the desire to pour himself out in adoration and in praise.

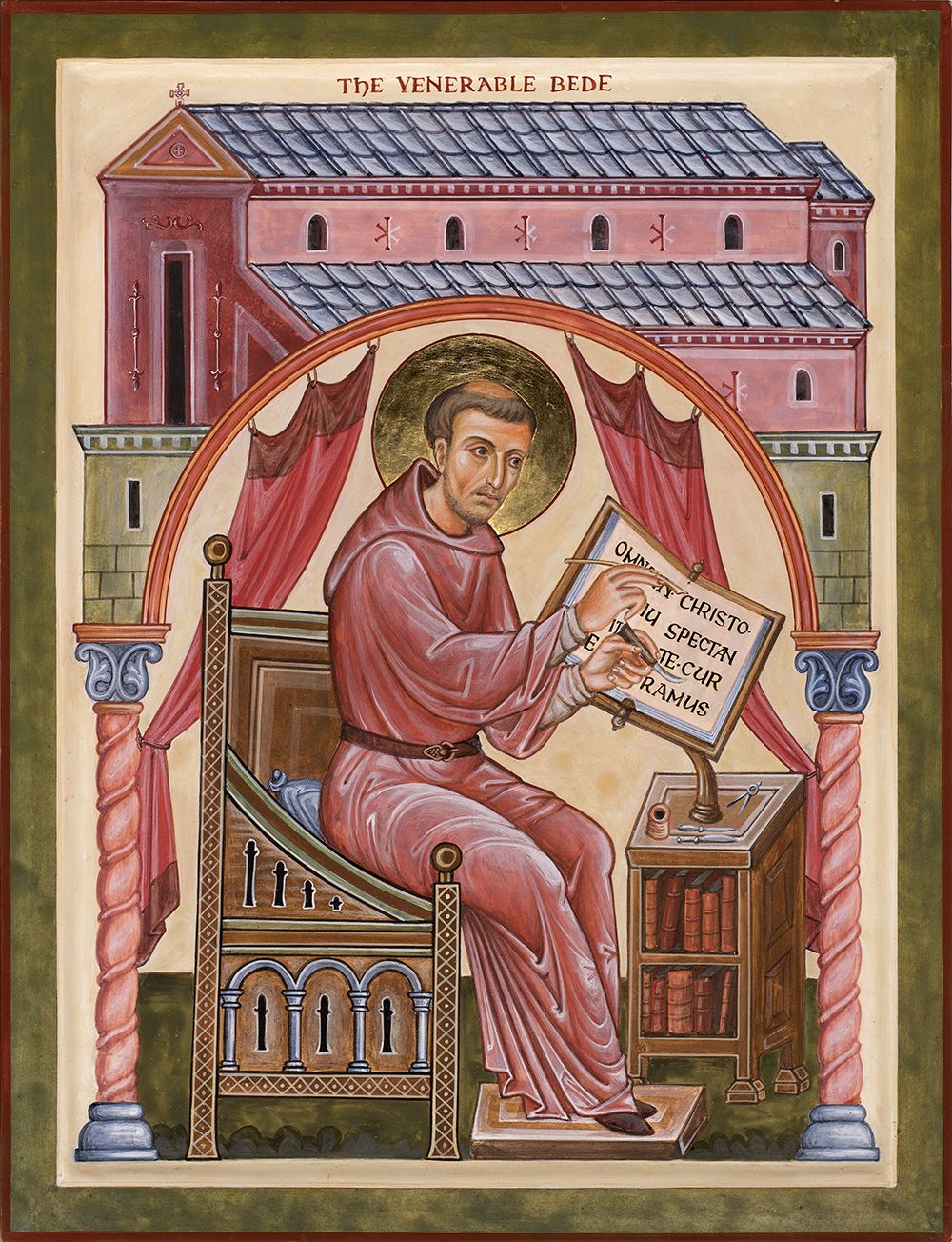

I have also seen monasteries fall into decline and wither away because “the love of letters” came to be divorced from “the desire for God”. Saint Bede (672–735) has long been considered the type of the complete monk devoted to the love of learning and the desire for God. He writes of himself: “I wholly applied myself to the study of Scripture; and amidst the observance of the monastic Rule and the daily charge of singing in church, I always took delight in learning, or teaching, or writing” (Historia Eccl. Anglorum, V, 24). All of the essential elements of Benedictine life are present in Saint Bede’s description of himself. After dictating the last part of his final book to Wilbert, his secretary; Saint Bede died, singing Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto. He died as he lived.

For a monk, “the love of letters” must lead to adoration and to doxology. It is said of Blessed Columba Marmion that when he lectured to the student monks at Mont–César, they would go straight from his lecture hall to the Blessed Sacrament, and there pour themselves out in adoration of the mysteries that Dom Marmion had expounded with such clarity and unction. Let me relate what one of Dom Marmion’s student monks wrote about him:

Being in charge both of the courses of dogma and of the spiritual formation of the young men (about twenty theology students from the Abbey of Maredsous, [living] at Mont–César in Louvain), the Father Prior broke the bread of truth abundantly for them. He knew from experience that the half–darkness of a grey and colourless atmosphere depressed souls and made them dull; he wanted light, an abundant light, radiant as the dawn. His was a rare quality: the professor of dogma had the gift of making us taste the revealed truths, of making us draw mystical conclusions out of them. When his lessons were over, one went, almost in spite of oneself, to kneel at the foot of the tabernacle, or to recollect oneself in the silence of the cell. Theology was a preparation for contemplation; we did not believe we really understood things until we had digested them in prayer. (A Benedictine Soul, Dom Pie de Hemptinne, (1880–1907), p. 49)

A monastery exists not to produce scholars but to produce saints. Where there is holiness of life there will be both fire and light. What Our Lord says concerning Saint John the Baptist — ille erat lucerna ardens et lucens, “He was a burning and a shining light” (John 5:35) — describes monastic holiness in every age. A monk burns and shines to the degree in which he spends himself in adoration and in the Opus Dei, or to the degree in which he abandons himself to the Will of God in the state of infirmity, and so unites himself to the Victim Christ. Ultimately, all that a monk does and suffers is ordered to the altar.