Tamquam Christus suscipiantur (LIII:1)

CHAPTER LIII. Of receiving Guests

4 Apr. 4 Aug. 4 Dec.

Let all guests that come be received like Christ Himself, for He will say: “I was a stranger and ye took Me in.” And let fitting honour be shewn to all, especially to such as are of the household of the faith, and to strangers. When, therefore, a guest is announced, let him be met by the Superior or the brethren, with all due charity. Let them first pray together, and thus associate with one another in peace; but the kiss of peace must not be offered until after prayer, on account of the delusions of the devil. In this salutation let all humility be shewn. At the arrival or departure of all guests, let Christ – who indeed is received in their persons – be adored in them, by bowing the head or even prostrating on the ground.When the guests have been received, let them be led to prayer, and then let the Superior, or any one he may appoint, sit with them. The law of God is to be read before the guest for his edification; and afterwards let all kindness be shewn him. The Superior may break his fast for the sake of the guest, unless it happen to be a principal fast-day, which may not be broken. The brethren, however, shall observe their accustomed fasting. Let the Abbot pour water on the hands of the guests; and himself, as well as the whole community, wash their feet after which let them say this verse: “We have received Thy mercy, O God, in the midst of Thy Temple.” Let special care be taken in the reception of the poor and of strangers, because in them Christ is more truly welcomed. For the very fear men have of the rich procures them honour.

In ancient times, especially in the East, hospitality was considered so sacred an obligation that it was almost an act of religion. In Book XIV of The Odyssey, Odysseus encounters the swineherd Eumaios in the forest. Eumaios exemplifies the Greek ideal of ξενία or hospitality:

“But enter this my homely roof, and see

Our woods not void of hospitality.

Then tell me whence thou art, and what the share

Of woes and wanderings thou wert born to bear.”

He said, and, seconding the kind request,

With friendly step precedes his unknown guest.

A shaggy goat’s soft hide beneath him spread,

And with fresh rushes heap’d an ample bed;

Jove touch’d the hero’s tender soul, to find

So just reception from a heart so kind:

And “Oh, ye gods! with all your blessings grace

(He thus broke forth) this friend of human race!”

The swain replied: “It never was our guise

To slight the poor, or aught humane despise:

For Jove unfold our hospitable door,

’Tis Jove that sends the stranger and the poor.”

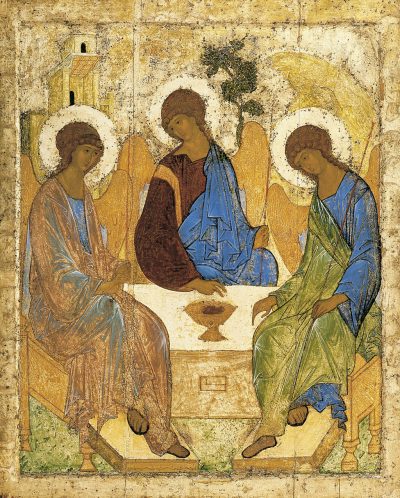

The advent of Our Lord Jesus Christ elevates the noble hospitality of the pagans, and even the hospitality of the righteous sons of Abraham, into a means of communion with the Most Holy Trinity. Saint Benedict explicitly quotes the words of Our Lord, “I was a stranger, and you took me in” (Matthew 25:35)”. There is, however, another utterance of Our Lord that illuminates from within this whole chapter:

Amen, amen I say to you, he that receiveth whomsoever I send, receiveth me; and he that receiveth me, receiveth him that sent me. (John 13:20)

For Saint Benedict, those who knock at the door of the monastery are sent by Christ. They are emissaries of the Lord Christ, our true King. In welcoming the emissaries of the King, it is the King Himself who is welcomed; and in opening the doors to Christ, the monastery is sanctified by the presence of the Father and of the Holy Ghost.

Saint Benedict concerns himself with the most pragmatic and homely details of hospitality; he does this because, in the light of faith, he sees hospitality as a kind of sacrament. It is characteristically Benedictine to find the mystic (that is, hidden divine things) in what is homely: in the humble realities of hearth and table; of clean water for tired feet and worn hands; in crisp white bedsheets, pillows, and warm blankets; in food and drink that is well–prepared and artfully presented. The guestmaster’s preparation of a guest room is no less important than the sacristan’s preparation of the altar. Blessed Schuster speaks of the medieval practice of abbot and monks going out in procession with thurible and processional cross to meet the approaching guests. The ceremony of welcome is, in effect, liturgical because the whole event is sacramental.

Saint Benedict presents a ritual order of welcome. First, the abbot and brethren go out, with all due charity, to meet the newly arrived guest or guests. The Gospels illumine this anticipation of the guest. The father of the prodigal son goes out to meet him while his son is yet on the road leading to the house: “And when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and was moved with compassion, and running to him fell upon his neck, and kissed him.” (Luke 15:20). The wise virgins go out to meet the Bridegroom while is yet on the way: “And at midnight there was a cry made: Behold the bridegroom cometh, go ye forth to meet him” (Matthew 25:6). Martha, the sister of Lazarus, goes out to meet the Lord who arrives at Bethany after her brother’s death: “Martha therefore, as soon as she heard that Jesus was come, went to meet him” (John 11:20).

Saint Benedict prescribes a liturgical gesture of adoration for the welcoming and departure of guests: the monks present are to bow or, even, to prostrate themselves on the ground. “Let Christ”, says Saint Benedict, “who indeed is received in their persons, be adored in them”. For Saint Benedict, the arrival of guests is a theological moment: an opportunity to recognise the presence of Christ and to adore Him. “For where there are two or three gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20). Nowhere does the secular gesture of shaking hands enter into the Benedictine ritual of welcome. In every detail of life, Saint Benedict would have his sons, “seek the things that are above; where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God” (Colossians 3:1).

Saint Benedict prescribes a liturgical gesture of adoration for the welcoming and departure of guests: the monks present are to bow or, even, to prostrate themselves on the ground. “Let Christ”, says Saint Benedict, “who indeed is received in their persons, be adored in them”. For Saint Benedict, the arrival of guests is a theological moment: an opportunity to recognise the presence of Christ and to adore Him. “For where there are two or three gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20). Nowhere does the secular gesture of shaking hands enter into the Benedictine ritual of welcome. In every detail of life, Saint Benedict would have his sons, “seek the things that are above; where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God” (Colossians 3:1).

After the initial greeting, there is prayer and, only then, conversation. “When the guests have been received, let them be led to prayer, and then let the Superior, or any one he may appoint, sit with them”. In our day, it is customary always to lead newly–arrived guests to the Oratory for a visit to the Most Blessed Sacrament. Upon entering the Oratory, the monk genuflects and kneels, remaining in silent adoration for a long moment; the guest will nearly always imitate what he sees the monk doing. Sometimes it happens that a guest steps back and remains standing, unwilling to participate in the act of adoration. In such an instance, the welcoming monk will silently present the guest to Our Lord, asking Our Lord to open the guest’s heart to the mystery of His hidden presence. The last verses of the hymn, Ubi caritas, come to mind:

Where charity and love are, God is there.

As we are gathered into one body,

Beware, lest we be divided in mind.

Let evil impulses stop, let controversy cease,

And may Christ our God be in our midst.

Where charity and love are, God is there.

And may we with the saints also,

See Thy face in glory, O Christ our God:

The joy that is immense and good,

Unto the ages through infinite ages. Amen.

Before offering refreshment, guests are to be offered the Word of God. “The law of God is to be read before the guest for his edification; and afterwards let all kindness be shewn him”. The guest who arrives at the monastery must be offered the Word of God before all else. Saint Benedict, in this way, identifies the traveler with the children of Israel in the Exodus:

He afflicted thee with want, and gave thee manna for thy food, which neither thou nor thy fathers knew: to shew that not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceedeth from the mouth of God. (Deuteronomy 8:3)

Here, Saint Benedict’s liturgical model emerges clearly. In the welcoming of guests, as in Holy Mass, the hearing of the Word of God precedes the offering of the Holy Sacrifice and the Holy Communion. In practice, this reading of the Word of God to guests takes place in three ways: at the Divine Office, in the refectory, and in spiritual conferences or colloquies with the guestmaster. It is never omitted, for the man who comes to the monastery is always, albeit unconsciously, asking for the Word of God.

Behold the days come, saith the Lord, and I will send forth a famine into the land: not a famine of bread, nor a thirst of water, but of hearing the word of the Lord. And they shall move from sea to sea, and from the north to the east: they shall go about seeking the word of the Lord, and shall not find it. (Amos 8:11–12)

On one or two occasions we have welcomed guests who indicated their disinclination to participate in the Divine Office and Holy Mass. The guestmaster, in as winsome a way possible, encourages such guests to participate in the monastery’s prayer. Prayer is what a monastic community has to offer. All the other commodities of hospitality can be found elsewhere. The monastic guesthouse is not a Bed and Breakfast establishment, nor is it a kind of hostel for tourists. The secularisation of a monastic guesthouse, or its operation as a business, is never a good sign. It suggests that the monastic community itself has lost sight of its single purpose. The words of Our Lord at Bethany can, in certain situations, be applied to whole communities: “Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: But one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:41–42).

The ceremonial of welcome culminates in the abbot washing the hands of the guest and in a meal. Saint Benedict considers that the washing of the feet of guests is integral to the rites of welcome. While we practice the washing of the hands of guests at the entrance to the refectory, the washing of the feet has come to be associated with the welcoming of men into the noviceship. More often than not, the journey to the monastery has been long and arduous. The man who knocks at the door of the cloister arrives with bruised and soiled feet. The postulant must be made to feel welcome and offered a sacramental expression of the refreshment promised by Christ.

Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you. Take up my yoke upon you, and learn of me, because I am meek, and humble of heart: and you shall find rest to your souls. For my yoke is sweet and my burden light. (Matthew 11:28:29)

Finally, guests are brought to the table. This is the culminating point of the Benedictine rites of hospitality. The abbot does not merely look on while the guests partake of what is set before them. He, or a monk designated by him, shares the meal with the guests and, in so doing, makes it a sign of communion that, effectively, points to the Most Holy Eucharist, the Sacrament of Unity. Benedictine hospitality has a Eucharistic finality.