Benedicant Deum qui ibi habitant (XL)

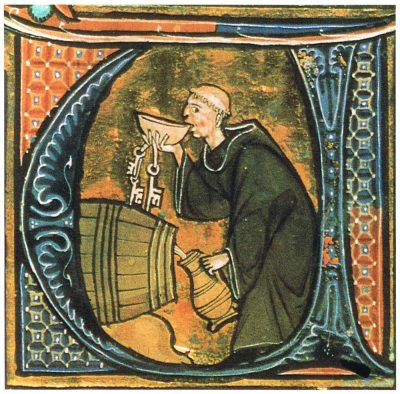

CHAPTER XL. Of the Measure of Drink

19 Mar. 19 July. 18 Nov.Every one hath his proper gift from God, one after this manner, another after that. And, therefore, it is with some misgiving that we appoint the measure of other men’s living. Yet, considering the infirmity of the weak, we think that one pint of wine a day is sufficient for each but let those to whom God gives the endurance of abstinence know that they shall have their proper reward. If, however, the situation of the place, the work, or the heat of summer require more, let it be in the power of the Superior to grant it; taking care in everything that surfeit or drunkenness creep not in. And although we read that wine ought by no means to be the drink of monks, yet since in our times monks cannot be persuaded of this, let us at least agree not to drink to satiety, but sparingly; because “wine maketh even the wise to fall away.” But where the necessity of the place alloweth not even the aforesaid measure, but much less, or none at all, let those who dwell there bless God and not murmur. This above all we admonish, that there be no murmuring among them.

Just as Saint Benedict provides for the monk’s daily measure of bread, so too does he provide for the monk’s daily measure of wine, considering, as always, the infirmity of the weak. Tamen infirmorum contuentes imbecillitatem. With regard to the daily provision of wine, Saint Benedict would seem to number the whole community among the infirmi, that is among the fragile, the feeble, or the unwell. Saint Benedict, setting an example for all who are set over a monastic family, makes the dispositions of the Apostle his own:

Factus sum infirmis infirmus, ut infirmos lucrifacerem. Omnibus omnia factus sum, ut omnes facerem salvos.

To the weak I became weak, that I might gain the weak. I became all things to all men, that I might save all. (1 Corinthians 9:22)

Our holy patriarch further refers to the teaching of the Apostle when he opens this chapter with words addressed to the Corinthians concerning celibacy:

For I would that all men were even as myself: but every one hath his proper gift from God; one after this manner, and another after that. (1 Corinthians 7:7)

And, again, he quotes the Apostle, concerning abstinence:

Every man shall receive his own reward, according to his own labour. (1 Corinthians 3:8)

Given, Saint Benedict’s dependence here on the teaching of Saint Paul, it is surprising that he does not quote the Apostle’s famous counsel to Timothy concerning wine, unless one finds an oblique reference to it in his earlier reference to infirmity:

Noli adhuc aquam bibere, sed modico vino utere propter stomachum tuum, et frequentes tuas infirmitates.

Do not still drink water, but use a little wine for thy stomach’s sake, and thy frequent infirmities. (1 Timothy 5:23)

The bread and wine of the monastic table point to the bread and wine that, placed upon the altar, become the Sacred Body and Precious Blood of Christ. It has been argued that the Holy Rule, being culturally conditioned by its origin in a Mediterranean and Roman context, cannot be a reference everywhere; it is however, precisely the Mediterranean and Roman origins of the Holy Rule that make it so wonderfully consonant with Sacred Scripture and with the whole sacramental economy.

Thou bringest bread out of the earth: and wine to cheer the heart of man. That he may make the face cheerful with oil: and that bread may strengthen man’s heart. (Psalm 103:14–15)

It is a peculiarly Northern European and Protestant prejudice that causes some to look askance at the bread, and wine, and oil of the monastic table. There has always been a certain moralistic censoriousness among those who, like the pharisees and lawyers described in the Gospel, pride themselves on being abstemious:

The Son of man is come eating and drinking: and you say: Behold a man that is a glutton and a drinker of wine, a friend of publicans and sinners. (Luke 7:34)

Although Saint Benedict acknowledges that, in the Verba Seniorum, Abba Poemen considered wine a drink unfit for monks, he does not impose on his monks the abstemiousness found among the Desert Fathers. He says, rather, “let us at least agree not to drink to satiety, but sparingly; because wine maketh even the wise to fall away”. The vice of drunkenness tends to prevail where wine is separated from the other elements of the traditional Mediterranean table: water, bread, and oil. When a man begins to drink alone, apart from the liturgy of the common table, he risks falling into over–indulgence. Saint Benedict warns of the danger of satiety, and rightly condemns excessive drinking.

The Lazio and and the Campania are among the finest wine–producing regions of Europe. Wine is so much a part of the culture that it is found even on the tables of people of very modest means. Saint Benedict’s monks would have come, for the most part, from wine–producing families in which they drank of the fruit of the vine from childhood. I myself have memories of eating and drinking with my Italian nonni at a table set up in the shade of the grape arbour in the back garden, and of being given my first little glass of diluted wine as a very small boy. The Holy Patriarch of Monte Cassino understood the old Neapolitan proverb, Una tavola senza vino è come una giornata senza sole, “A table without wine is like a day without sunshine”. There is, I think, an echo of this proverb in Hilaire Belloc’s famous quatrain:

Wherever the Catholic sun doth shine

There’s always laughter and good red wine.

At least I’ve always found it so,

Benedicamus Domino!

The quantity of wine that Saint Benedict, following the Rule of the Master, prescribes—a hemina—has been various translated and measured. The general consensus is that it is half a flagon or a about half a litre. It is understood that Saint Benedict’s monks would have added water to their wine, as was the general custom in antiquity. Saint Benedict foresees that there will be monasteries in places where it will be difficult or impossible to procure wine for the daily table. When deprived of wine or when it is in short supply, monks are not to murmur. They are to raise their voices in blessing, “giving thanks always for all things, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, to God and the Father” (Ephesians 5:20). The chapter ends, not with a sentence concerning wine, but rather with the injunction to bless God and forswear murmuring. Murmuring, for Saint Benedict, is the most toxic of vices.

Benedicant Deum qui ibi habitant et non murmurent. Hoc ante omnia admonentes ut absque murmurationibus sint.

Let those who dwell there bless God and not murmur. This above all we admonish, that there be no murmuring among them.