Christo omnino nihil praeponant (LXXII)

CHAPTER LXXII. Of the good zeal which Monks ought to have

30 Apr. 30 Aug. 30 Dec.

As there is an evil zeal of bitterness, which separateth from God, and leads to hell, so there is a good zeal, which keepeth us from vice, and leadeth to God and to life everlasting. Let monks, therefore, exert this zeal with most fervent love; that is, “in honour preferring one another.” Let them most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of mind. Let them vie with one another in obedience. Let no one follow what he thinketh good for himself, but rather what seemeth good for another. Let them cherish fraternal charity with chaste love, fear God, love their Abbot with sincere and humble affection, and prefer nothing whatever to Christ. And may He bring us all alike to life everlasting.

I shall always remember a retreat preached by a Benedictine monk in 1990. The good Father, who was Lebanese, spoke with a compelling warmth on the wonderful correspondence between Chapter LXXII of the Holy Rule and Chapter V of the Epistle to the Ephesians. To this day, whenever I read or listen to Chapter LXXII, I hear in it remarkable resonances with Saint Paul. Saint Benedict speaks first of an evil zeal of bitterness (zelus amaritudinis) which separates from God, and leads to hell. The Apostle, in the Epistle to the Ephesians, likewise speaks of bitterness, linking it to other vices. He contrasts these things with the kindness, mercy, and forgiveness that characterise men forgiven by God in Christ.

Let all bitterness, and anger, and indignation, and clamour, and blasphemy, be put away from you, with all malice. And be ye kind one to another; merciful, forgiving one another, even as God hath forgiven you in Christ. (Ephesians 4:31–32)

Saint Benedict would have us practice the good zeal, “which keepeth us from vice, and leads to God and to life everlasting”. The first and last sentences of Chapter LXXII end with the phrase ad vitam aeternam, “to life everlasting. This reveals, I think, the impression left in Saint Benedict’s soul by the experience that Saint Gregory relates in Chapter XXXV of the Second Book of the Dialogues:

The man of God, Benedict, being diligent in watching, rose early up before the time of matins (his monks being yet at rest) and came to the window of his chamber, where he offered up his prayers to almighty God. Standing there, all on a sudden in the dead of the night, as he looked forth, he saw a light, which banished away the darkness of the night, and glittered with such brightness, that the light which did shine in the midst of darkness was far more clear than the light of the day. Upon this sight a marvellous strange thing followed, for, as himself did afterward report, the whole world, gathered as it were together under one beam of the sun, was presented before his eyes.

Saint Gregory explains that Saint Benedict was, in some way, lifted above himself and into the light of God so as to see all created things from the divine perspective, sub specie aeternitatis. Saint Benedict’s heart, while he was yet on earth, was already fixed, as we said in yesterday’s Collect, ubi vera sunt gáudia, “where true joys are to be found”. Saint Gregory explains that Saint Benedict saw the whole world in this way, not by any shrinking of the world, but by a divine enlargement of the soul. Saint Benedict’s soul was ravished into “the things that are above; where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God” (Colossians 3:1). From the perspective of everlasting life, Saint Benedict saw “how small all earthly things were”.

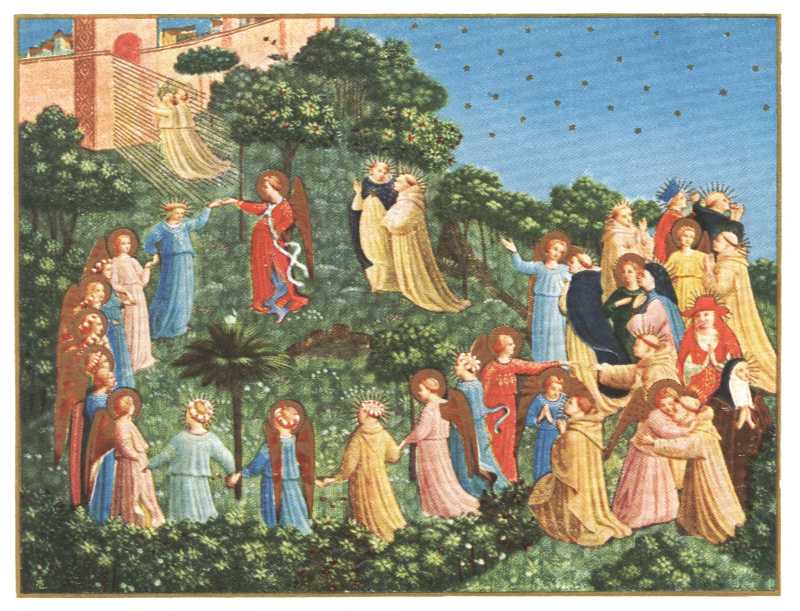

It seems to me that Saint Benedict wrote Chapter LXXII in this light; in it he condenses all that we monks need to practice in order to enter everlasting life. Saint Benedict would have us understand that everlasting life begins here and now in the manner in which we practice a most fervent love, in honour preferring one another. Blessed Fra Angelico depicted this perfectly ordered charity in his painting of the circle dance of the saints in paradise. Each saint defers to the other; the dance is ordered by charity, and humility is the pattern of its steps. There is an American monastery where the monks practice circle dancing as an expression of the graceful order of charity and of the inner dynamic of community life. While I do not propose that we take up circle dancing, I do understand that it can be, as it was for Blessed Fra Angelico, an expression of the pattern of what Saint Augustine calls “rightly ordered love” (City of God, XV:23). Saint Thomas says:

It is charity which directs the acts of all other virtues to the last end, and which, consequently, also gives the form to all other acts of virtue: and it is precisely in this sense that charity is called the form of the virtues, for these are called virtues in relation to “informed” acts. (Second Part of the Second Part, Q. 23, Art.8)

So it is in the circle dance — the well–ordered movement — of monastic life. It is charity which directs the steps of the dancers, who, in honour, prefer one another. It is charity which gives form to the dance. Our earthly life is short. Everlasting life awaits us. For the man who lives with the perspective of eternity before him, there can be no room for pettiness; such a man has no time to be miserly, calculating, and small–minded. Never hold onto a grievance. Never nourish resentment, or brood over injuries, or fall back into the lex talionis, exacting “eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot” (Exodus 21:24). The Benedictine spirit is one of large–mindedness, magnanimity, generosity, graciousness, and deferential charity. The miserable little vice of pettiness and the narrowness of the calculating spirit make the cloister a suffocating place. The virtues of graciousness, generosity, and self–effacing love make the cloister a little paradise, that is, a place where all are united in charity and in the praise of God, and where joy abounds. The Apostle says to his dear Ephesians:

Be ye therefore followers of God, as most dear children; and walk in love, as Christ also hath loved us, and hath delivered himself for us, an oblation and a sacrifice to God for an odour of sweetness. (Ephesians 5:1–2)

Saint Benedict describes for us in detail and in the most practical way what it means to “walk in love as Christ hath loved us”:

Let them most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of mind. Let them vie with one another in obedience. Let no one follow what he thinketh good for himself, but rather what seemeth good for another.

I have learned, over the years, not to regret my own infirmities, and not to regret yours, whether of body or of mind. On the contrary, I have come to see that where infirmities abound, there God gives scope for charity towards one another, for patience, and, for a confident and unremitting recourse to the grace of Christ. Who does not recognise himself in the Apostle?

There was given me a sting of my flesh, an angel of Satan, to buffet me. For which thing thrice I besought the Lord, that it might depart from me. And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee: for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful. (2 Corinthians 12:7–10)

This is our life: relying on the grace of Christ deployed in all our infirmities, we are to cherish fraternal charity with chaste love, fear God, love the Abbot with sincere and humble affection, and prefer nothing whatever to Christ. These are the steps of the well–ordered dance. And may Christ, as Saint Benedict concludes in this chapter, “bring us all alike to life everlasting”.