Of the Weekly Servers in the Kitchen (XXXV:2)

14 Mar. 14 July. 13 Nov.

Let the weekly servers take each a cup of drink and a piece of bread over and above the refection, that so they may serve their brethren, when the hour cometh, without murmuring or great labour. On solemn days, however, let them forbear until after Mass. On Sunday, as soon as Lauds are ended, let both the incoming and the outgoing servers fall on their knees before all, in the Oratory, and ask their prayers. Let him who endeth his week, say this verse: “Blessed art Thou Lord God, Who hast helped me and comforted me;” which being thrice repeated, he shall receive the blessing. Let him that beginneth his week follow, and say: “O God, come to my assistance: O Lord, make haste to help me.” Let this likewise be thrice repeated by all; and having received the blessing, let him enter on his office.

We continue to read Chapter XXXV. Chapters XXXI—XLI are a kind of handbook for the cellarer. Following the tradition of the monks of Palestine and Mespotamia, Saint Benedict would have his monks care diligently for the property of the monastery, for all that the monastery contains belongs to the Lord.

They believe not only that they themselves are not their own, but also that everything that they possess is consecrated to the Lord. Wherefore if anything whatever has once been brought into the monastery they hold that it ought to be treated with the utmost reverence as an holy thing. And they attend to and arrange everything with great fidelity, even in the case of things which are considered unimportant or regarded as common and paltry, so that if they change their position and put them in a better place, or if they fill a bottle with water, or give anybody something to drink out of it, or if they remove a little dust from the oratory or from their cell they believe with implicit faith that they will receive a reward from the Lord. (Cassian, Institutes, Book IV, Chapter 20)

Saint Gregory says of Saint Benedict that, “He wrote a rule for his monks . . . excellent for discretion” (Second Book of the Dialogues, Chapter 36). The word discretion does not sound in modern ears as it would have sounded in the ear of Saint Gregory and his contemporaries. Moderns understand discretion to pertain to a way of reserving confidential information or to the freedom given one to take a decision according to the lights one has. For Cassian and for the ancient monastic fathers, discretion meant the judgment whereby a man wisely sorts out what is right in a given situation, avoiding excess of any kind. Cassian says that “discretion is the mother of all virtues, as well as their guardian and regulator” (Conference II, Chapter 4).

Saint Benedict wants to spare the weekly servers weakness, fatigue, and headaches, all of which can come from not having eaten or drunk. The servers are to eat and drink “so they may serve their brethren, when the hour cometh, without murmuring or great labour”. This paternal solicitude for the well–being of the brethren is characteristically Benedictine.

The liturgical blessing of the incoming and outgoing servers early on Sunday morning—the traditional hour for ordinations in Rome— express the quasi–sacramental character of serving in the refectory. Saint Benedict may have had in mind the service of the first deacons who, according to Acts 6:2, were charged specifically with the service of the tables. Cassian speaks of the blessing of servers on Sunday evening:

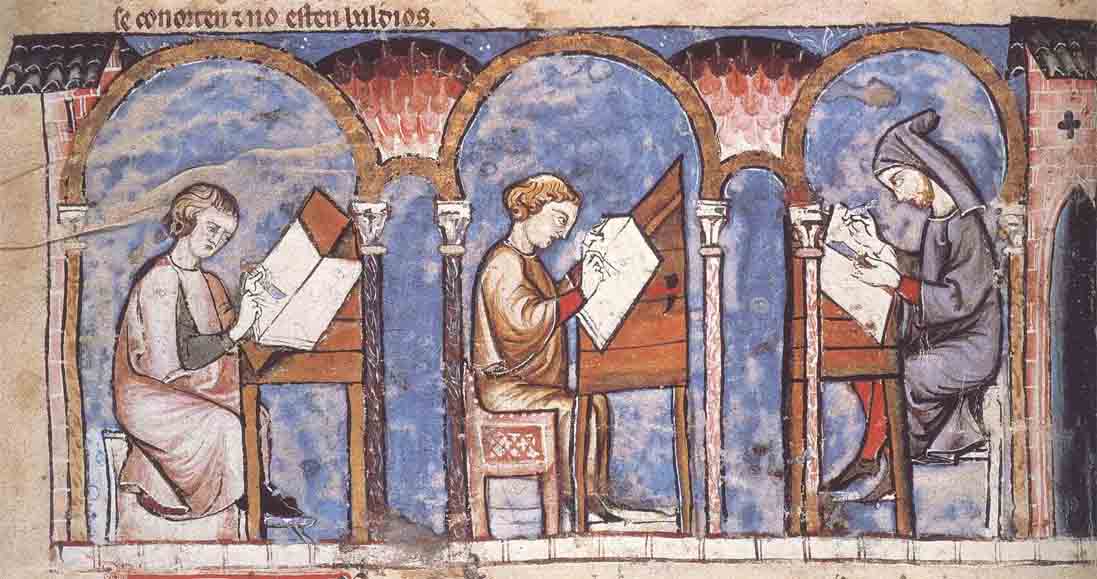

Each one who undertakes these weeks is on duty and has to serve until supper on Sunday, and when this is done, his duty for the whole week is finished, so that, when all the brethren come together to chant the Psalms (which according to custom they sing before going to bed) those whose turn is over wash the feet of all in turn, seeking faithfully from them the reward of this blessing for their work during the whole week, that the prayers offered up by all the brethren together may accompany them as they fulfil the command of Christ, the prayer, to wit, that intercedes for their ignorances and for their sins committed through human frailty, and may commend to God the complete service of their devotion like some rich offering. And so on Monday after the Mattin hymns they hand over to others who take their place the vessels and utensils with which they have ministered, which these receive and keep with the utmost care and anxiety, that none of them may be injured or destroyed, as they believe that even for the smallest vessels they must give an account, as sacred things, not only to a present steward, but to the Lord, if by chance any of them is injured through their carelessness. (Institutes, Book IV, Chapter 19)

On Maundy Thursday, according to a medieval tradition still observed in some monasteries today, the abbot himself, clothed in a white apron, serves the brethren at table. This he does in imitation of Our Lord who, having taken a towel, girded himself and washed the feet of His apostles. During the same meal, the reader (wearing, if he is a priest or deacon, a white stole over his cuculla) chants chapters XIII through XVII of Saint John’s Gospel. The monastic meal has, at all times, a Eucharistic quality. The very disposition of the refectory suggests that it is a kind of basilica: the great crucifix over the abbot’s table, the pulpit for the reader, and the tables arranged in two facing “choirs” all contribute to making the meal an extension of the Opus Dei.