The fifth degree of humility

2 Feb. 3 June. 3 Oct.

The fifth degree of humility is, not to hide from one’s Abbot any of the evil thoughts that beset one’s heart, or the sins committed in secret, but humbly to confess them. Concerning which the Scripture exhorteth us, saying: “Make known thy way unto the Lord, and hope in Him.” And again: “Confess to the Lord, for He is good, and His mercy endureth for ever.” So also the prophet saith: “I have made known to Thee mine offence, and mine iniquities I have not hidden. I will confess against myself my iniquities to the Lord: and Thou hast forgiven the wickedness of my heart.”

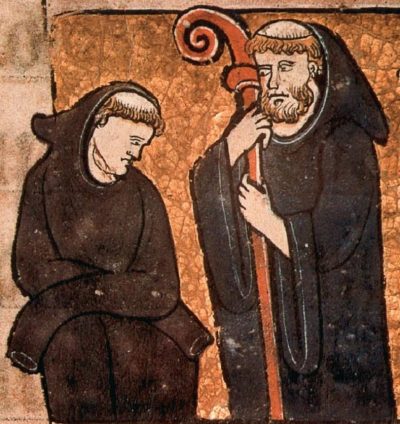

Saint John Cassian says that “the devil, subtle as he is, cannot ruin or destroy a junior unless he has enticed him either through pride or through shame to conceal his thoughts”. The thoughts of which one is most ashamed are the very thoughts that need to be brought into the light. Brothers sometimes makes themselves anxious because they do not know how to confess their evil thoughts, or because they think it is necessary to do so systematically and in a logical order. The manifestation of one’s evil thoughts to the spiritual father is simple: it is like turning a large bag full of rubbish upside down, and shaking it until everything falls out of it. Things will fall out in no particular order, and will be scattered in different directions. This is of no importance. What matters is that the bag of one’s evil thoughts be emptied out. Sometimes it is necessary to sort through the rubbish, in order to verify its composition. More often than not, it is better to leave it in the light, allowing it to disintegrate, and trusting the holy angels to dispose of the residue. Cassian discusses why young monks must be taught to reveal their thoughts to the abbot:

They are next taught not to conceal by a false shame any itching thoughts in their hearts, but, as soon as ever such arise, to lay them bare to the senior, and, in forming a judgment about them, not to trust anything to their own discretion, but to take it on trust that the matter is good or bad which is considered and pronounced so by the examination of the senior. Thus it results that our cunning adversary cannot in any way circumvent a young and inexperienced monk, or get the better of his ignorance, or by any craft deceive one whom he sees to be protected not by his own discretion but by that of his senior, and who cannot be persuaded to hide from his senior those suggestions of his which like fiery darts he has shot into his heart; since the devil, subtle as he is, cannot ruin or destroy a junior unless he has enticed him either through pride or through shame to conceal his thoughts. For they lay it down as an universal and clear proof that a thought is from the devil if we are ashamed to disclose it to the senior. (Institutes, Book IV, Chapter 9)

In the Conferences, there is this compelling story of the brother who was addicted to stealing and eating one biscuit a day. Things got to the point where he was no longer eating the biscuit; the biscuit rather was eating him:

While, said he, I was still a lad, and stopping with Abbot Theonas, this habit was forced upon me by the assaults of the enemy, that after I had supped with the old man at the ninth hour, I used every day secretly to hide a biscuit in my dress, which I would eat on the sly later on without his knowing it. And though I was constantly guilty of the theft with the consent of my will, and the want of restraint that springs from desire that has grown inveterate, yet when my unlawful desire was gratified I would come to myself and torment myself over the theft committed in a way that overbalanced the pleasure I had enjoyed in the eating. And when I was forced not without grief of heart to fulfil day after day this most heavy task required of me, so to speak, by Pharaoh’s taskmasters, instead of bricks, and could not escape from this cruel tyranny, and yet was ashamed to disclose the secret theft to the old man, it chanced by the will of God that I was delivered from the yoke of this voluntary captivity, when certain brethren had sought the old man’s cell with the object of being instructed by him. And when after supper the spiritual conference had begun to be held, and the old man in answer to the questions which they had propounded was speaking about the sin of gluttony and the dominion of secret thoughts, and showing their nature and the awful power which they have so long as they are kept secret, I was overcome by the power of the discourse and was conscience stricken and terrified, as I thought that these things were mentioned by him because the Lord had revealed to the old man my bosom secrets; and first I was moved to secret sighs, and then my heart’s compunction increased and I openly burst into sobs and tears, and produced from the folds of my dress which shared my theft and received it, the biscuit which I had carried off in my bad habit to eat on the sly; and I laid it in the midst and lying on the ground and begging for forgiveness confessed how I used to eat one every day in secret, and with copious tears implored them to entreat the Lord to free me from this dreadful slavery. Then the old man:

Have faith, my child,said he,Without any words of mine, your confession frees you from this slavery. For you have today triumphed over your victorious adversary, by laying him low by your confession in a manner which more than makes up for the way in which you were overthrown by him through your former silence, as when, never confuting him with your own answer or that of another, you had allowed him to lord it over you, according to that saying of Solomon’s: ‘Because sentence is not speedily pronounced against the evil, the heart of the children of men is full within them to do evil:’ and therefore after this exposure of him that evil spirit will no longer be able to vex you, nor will that foul serpent henceforth make his lurking place in you, as he has been dragged out into light from the darkness by your life-giving confession.The old man had not finished speaking when lo! A burning lamp proceeding from the folds of my dress filled the cell with a sulphureous smell so that the pungency of the odour scarcely allowed us to stay there: and the old man resuming his admonition said Lo! The Lord has visibly confirmed to you the truth of my words, so that you can see with your eyes how he who was the author of His Passion has been driven out from your heart by your life-giving confession, and know that the enemy who has been exposed will certainly no longer find a home in you, as his expulsion is made manifest. And so, as the old man declared, said he, the sway of that diabolical tyranny over me has been destroyed by the power of this confession and stilled for ever so that the enemy has never even tried to force upon me any more the recollection of this desire, nor have I ever felt myself seized with the passion of that furtive longing. (Conferences, Book II, Chapter 11)

The whole monastic tradition attests to the importance of confessing one’s thoughts. By doing so, a monk disarms them, neutralises them, and frees himself of their toxic influence. The fifth degree of humility does not refer primarily to sacramental confession. The Sacrament of Penance is for the simple, unadorned confession of one’s sins: the priest hears the penitent’s avowals and his act of contrition; he gives the penitent a suitable penance; and pronounces the words of absolution. It is generally not helpful for a confessor who is not a monk to attempt to give specific counsels to a monk–penitent. Although he be of impeccable orthodoxy and have the best intentions, a confessor not at home in the monastic tradition risks giving counsels that are at variance with the Holy Rule or with the instructions of the abbot. It is always better for a monk to seek from his abbot, and from the abbot’s trusted and authorised collaborators, the light, comfort, and direction that, within the monastery, they have the grace of state to give .