How many Psalms are to be sung at these Hours (XVII)

CHAPTER XVII. How many Psalms are to be sung at these Hours

20 Feb. 21 June. 21 Oct.We have now disposed the order of the psalmody for the Night-Office and for Lauds: let us proceed to arrange for the remaining Hours. At Prime, let three Psalms be said separately and not under one Gloria. The hymn at this Hour is to follow the verse, Deus in adjutorium, before the Psalms be begun. Then at the end of the three Psalms, let one lesson be said, with a versicle, the Kyrie eleison, and the Collect. Tierce, Sext and None are to be recited in the same way, that is, the verse, the hymn proper to each Hour, three Psalms, the lesson and versicle, Kyrie eleison, with the Collect. If the community be large, let the Psalms be sung with antiphons: but if small, let them be sung straight forward. Let the Vesper Office consist of four Psalms with antiphons: after the Psalms a lesson is to be recited; then a responsory, a hymn and versicle, the canticle from the Gospel, the Litany and Lord’s Prayer, and finally the Collect. Let Compline consist of the recitation of three Psalms to be said straight on without antiphons; then the hymn for that Hour, one lesson, the versicle, Kyrie eleison, the blessing and the Collect.

Saint Benedict is very thorough. Today he sets forth the order of service to be followed at the Little Hours, Vespers, and Compline. The structure for Prime, Terce, Sext, and None is the same: the hymn, three psalms, each with a Gloria Patria, a lesson, a versicle, Kyrie eleison, and the conclusion. The structure at Vespers is: four psalms with antiphons, a lesson, a responsory, a hymn, a versicle, the canticle from the Gospel, the litany, the Pater Noster, and the conclusion. At Compline, the structure is similar, except that the hymn follows the three psalms, and there is, at the end a blessing of dismissal. It is a wonderful thing that, even today, we recognise in our own order of service for the Hours the very same structure put in place by our father Saint Benedict. With regard to the Opus Dei, the Holy Rule constitutes, for all monks who profess it, the supreme liturgical authority and reference.

In 1968, the same year that Pope Paul VI issued Sacrificium Laudis, charging those bound to the choral Office with maintaining the use of Latin and of Gregorian Chant, the Benedictine Confederation obtained from the Consilium for Implementing the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy an indult for wide experimentation with the Divine Office. In 1977, at the request of the Abbot Primate Rembert Weakland, the Congregation for the Sacraments and for Divine Worship, approved a Thesaurus Liturgia Horarum Monasticae, which authorised a number of variations on the order of the Opus Dei set forth in the Holy Rule, including the distribution of the 150 psalms over two weeks or longer. The four distributions of the psalter proposed in the Thesaurus spawned hundreds of others. In practice, the abbot of each monastery became the arbitor, if not the author, of his community’s ordo celebrationis. The dispositions proposed in 1977 in no way affect the fundamental authority of the Holy Rule, which enjoins monks to celebrate seven day Hours and one nocturnal Hour; to keep to the number of psalms set forth for each hour, including the twelve psalms (or divisions of psalms) of the Night Office; and to recite the 150 psalms over one week.

At the practical level, each monk is to apply himself with joyful diligence to the “givenness” of the Opus Dei. For one brother this will mean finding in each psalm a verse, a phrase, a word to be stored away in the granary of the heart. It is not necessary, nor is it even possible while chanting the psalms in choir, to apply oneself to the literal and spiritual senses of each verse. This is a task reserved for lectio divina. It is, however, possible and necessary to discover in each psalm the spark of fiery prayer that shines first in one verse and then in another.

The monk who applies himself to learning by heart even a single word from each Office will, at the end of the day, have learned 8 words. At the close of a week, he will have learned as a many as 56 words; at the end of a month, 224 words; at the end of a liturgical year something in the order of 2000 words; and, after ten years in the monastery, 20,000 words . . . all words of life. “For thy servant keepeth them, and in keeping them there is a great reward” (Psalm 18:12).

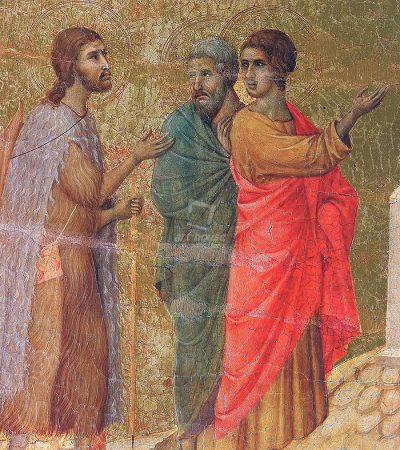

In the hours of darkness and desolation that mark every man’s monastic journey, it pleases the Holy Ghost to bring forth from the well–supplied granary of the heart precisely the right word to illumine the mind, inflame the heart, and bend the heart to “the things that are pleasing to God” (Baruch 4:4). Thus can monks, long accustomed to reciting the psalms by day and by night, say with the disciple of Emmaus: “Was not our heart burning within us, whilst he spoke in the way, and opened to us the scriptures?” (Luke 24:32).