How many Psalms are to be said at the Night Hours (IX)

CHAPTER IX. How many Psalms are to be said at the Night Hours

11 Feb. 12 June. 12 Oct.In winter time, after beginning with the verse, “O God, come to my assistance; O Lord, make haste to help me,” with the Gloria, let the words, “O Lord, Thou wilt open my lips, and my mouth shall declare Thy praise,” be next repeated thrice; then the third Psalm, with a Gloria, after which the ninety-fourth Psalm is to be said or sung, with an antiphon. Next let a hymn follow, and then six Psalms with antiphons. These being said, and also a versicle, let the Abbot give the blessing and, all being seated, let three lessons be read by the brethren in turns, from the book on the lectern. Between the lessons let three responsories be sung – two of them without a Gloria, but after the third let the reader say the Gloria: and as soon as he begins it, let all rise from their seats out of honour and reverence to the Holy Trinity. Let the divinely inspired books, both of the Old and New Testaments, be read at the Night-Office, and also the commentaries upon them written by the most renowned, orthodox and Catholic Fathers. After these three lessons with their responsories, let six more Psalms follow, to be sung with an Alleluia. Then let a lesson from the Apostle be said by heart, with a verse and the petition of the Litany, that is, Kyrie eleison. And so let the Night-Office come to an end.

I did not have time yesterday to develop one key sentence of Chapter VIII. Before attempting to say anything about Chapter IX, I shall, then, return briefly to the sentence in question.

And let the time that remains after the Night-Office be spent in study by those brethren who have still some part of the Psalter and lessons to learn.

Saint Benedict concerns himself with the profitable use of the time between Vigils (or Matins, or Nocturns) and Lauds. He indicates that it ought to be used for the study of the Psalter and of the lessons read at the Divine Office from Sacred Scripture and from the Fathers. For a Benedictine monk, the study of the Psalter is a lifelong work. The psalms are an inexhaustible mine from which the monk learns to extract a precious gold. The psalms are a monk’s daily bread. They are to him, at the various seasons and hours of his life, like the sweetest honey, or like fresh clean water, or like an astringent vinegar, or even like the sands of the desert.

Saint Benedict’s monk is bound to this lifelong, persevering study of the psalms. The psalms give us nothing less than the prayer of Christ to the Father, uttered in the grace and sweetness of the Holy Ghost. The psalms become a kind of holy communion with all the sentiments, desires, sufferings, joys, and glories of the Heart of Jesus. An old monastic adage says: Semper in ore psalmus; semper in corde Christus. The monk who, at every moment, has a psalm verse in his mouth will, at every moment, have Christ, and the very prayer of Christ, in his heart.

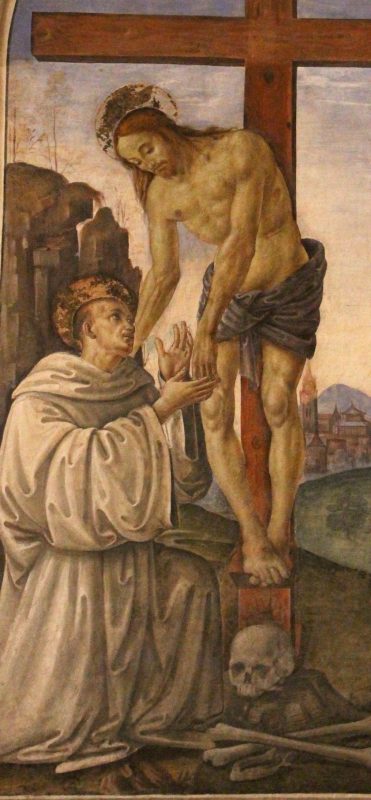

Saint Benedict begins the Night Office with Psalm 3 because of its striking Christological content: “I have slept and taken my rest: and I have risen up, because the Lord hath protected me” (Psalm 3:6). The holy patriarch would have his monks enter into the grace of identification—and real union—with Christ in the mystery of His death and resurrection. Sleep is an image of death, and rising in the morning is an image of the resurrection. All that the monk does, from lying down upon his bed to standing again on his feet in the morning, is subsumed into the mysteries of Christ. “And I live, now not I; but Christ liveth in me. And that I live now in the flesh: I live in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and delivered himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).

And the Lord God said: It is not good for man to be alone: let us make him a help like unto himself. . . . Then the Lord God cast a deep sleep upon Adam: and when he was fast asleep, he took one of his ribs, and filled up flesh for it. And the Lord God built the rib which he took from Adam into a woman: and brought her to Adam. And Adam said: This now is bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called woman, because she was taken out of man. (Genesis 2:18; 21-23)

Jesus, the New Adam, slept the sleep of death upon the marriage bed of the cross; it was during this sleep that His Bride, the Church, the New Eve was born of His sacred side. The monk knows that the Lord gives to His beloved in sleep. It is when the soul sleeps, dead to all things around it, that God makes her most fruitful.

Immediately after Psalm 3 comes the Invitatory Antiphon with Psalm 94; it is, as its designation suggests, a pressing invitation to adoration. Venite, adoremus. It constitutes the narthex or vestibule of the Night Office; from the narthex the soul peers into the temple and sees, in the distance, the altar and the tabernacle of the Divine Presence, the object of all her desires.

With the hymn—Saint Benedict calls it the Ambrosian because so many hymns of the Divine Office were composed in the school of Saint Ambrose at Milan—the pace quickens. It is as if the choir cannot wait to settle into the long watch of psalmody that follows: six psalms with antiphons. After the abbot’s blessing over both the reader and the listeners, three lessons with their responsories follow. The ancient rhythm of call and response is thus embedded in the Night Office. Then there is more psalmody: again six psalms with an Alleluia. Psalmody quiets the soul and disposes one to receive the visit of the Word. Saint Bernard knew this experience well. He describes it in a sermon:

He is life and power, and as soon as he enters in, he awakens my slumbering soul; he stirs and soothes and pierces my heart, for before it was hard as stone, and diseased. So he has begun to pluck out and destroy, to build up and to plant, to water dry places and illuminate dark ones; to open what was closed and to warm what was cold; to make the crooked straight and the rough places smooth, so that my soul may bless the Lord, and all that is within me may praise his holy name. So when the Bridegroom, the Word, came to me, he never made known his coming by any signs, not by sight, not by sound, not by touch. It was not by any movement of his that I recognized his coming; it was not by any of my senses that I perceived he had penetrated to the depth of my being. Only by the movement of my heart, as I have told did I perceive his presence; and I knew that by the power of his might my faults were put to flight and my human yearnings brought into subjection. I have marveled at the depth of his wisdom when my secret faults have been revealed and made visible, and in the very slightest amendment of my way of life I have experiences his goodness and mercy; in the renewal and remaking of the spirit of my mind, that is of my inmost being, I have perceived the excellence of his glorious beauty, and when I contemplate all these things I am filled with awe and wonder at his manifold greatness. (Sermon 74 on the Song of Songs)