Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 11

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

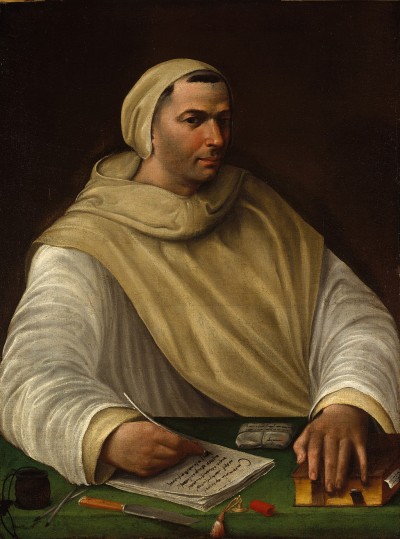

Letter 11: Anthony

Dear Father,

Thank you for taking the time to answer some of my questions. I especially appreciated what you wrote me concerning the place of the Blessed Virgin Mary in your Benedictine life. Somehow, I had never made the connection between Our Lady and the Rule of Saint Benedict. You gave me an entirely new insight into the role of Mary in the monastic life. Up until now, I understood devotion to Our Lady in terms of saying the rosary, wearing the scapular or the miraculous medal, and going on pilgrimage to Knock and to Lourdes. I am familiar with the total consecration to Mary as Saint Louis de Montfort taught it and, at different moments in my own journey, I have tried to make it.

What strikes me, about in what you wrote about devotion to Mary in the monastic life, is that you see it, not merely in terms of certain outward practices and prayers, but as something really essential. As you wrote, Mary is the pattern of monks. If I understand you correctly, you are saying that a monk does exactly what Mary is described as doing in Saint Luke’s Gospel: “But Mary kept all these words, pondering them in her heart”. I shall continue to pray about this. I feel that new horizons are opening before me.

Now, Father, may I ask you to explain further the place of Eucharistic adoration in your life? My sense is that “perpetual adoration” at Silverstream is not exactly what comes to mind when I think of “perpetual adoration”. I also heard from friends who visited Silverstream that you do not, as a rule, have exposition of the Blessed Sacrament every day. I find this confusing. I always thought that adoration of the Blessed Sacrament required exposition. In my parish, for example, there is exposition every day in an “adoration chapel”. An extraordinary minister (or the sacristan) opens the tabernacle and places the Host in the monstrance. This is all I have ever known and I assumed that adoration and exposition always go together. Why is this not the case at Silverstream Priory? Sorry, Father, for assailing you with questions, but I really do want to understand better what you monks are about.

I hope to visit Silverstream soon. Things are busy in my life and it is not easy for me to get away for a few days, but the more I learn about you the more I want to visit. I will try to get out to Silverstream before the end of the year.

Anthony

Dear Anthony,

You do persevere in seeking answers to your questions! I shall try to respond to your questions concerning adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament as we practice it at Silverstream. We Benedictine Monks of Perpetual Adoration see in the Sacred Host the radiant divine icon of what we are called to become. A man becomes what he contemplates. So it is with us: the more we contemplate the Sacred Host, the more do we begin to resemble what we contemplate. Saint Paul says, “We all beholding the glory of the Lord with open face, are transformed into the same image from glory to glory, as by the Spirit of the Lord” (2 Corinthians 3:18).

The hidden Christ, the silent Christ, the humble Christ of the Tabernacle models the virtues of the Rule of Saint Benedict in the most astonishing way, and communicates those same virtues to those who linger in His company. Far from being a baroque adornment detracting from some mythical primitive Benedictine sobriety, Eucharistic adoration is the wellspring of the holiness that Saint Benedict describes in his Rule.

Adoration of the Sacred Host is the school of hiddenness,

— of silence,

— of solitude,

— of humility,

— of obedience,

— of servanthood,

— of an abiding love that calls no attention to itself,

— of ceaseless prayer to the Father,

— of the Work of God,

— of compassion for sinners,

— of burning love for souls,

— of gentleness towards the weak,

— of Divine Hospitality,

— of monastic perfection, that is, the passion for God alone.

All of these things are found in the text of the Holy Rule, and all of them are found in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, as in their very source. The Rule of Saint Benedict describes the fruits of grace in a monk; the Sacred Host shows forth and, even more,causes the same fruits of grace in a monk.

The word “Host” means sacrificial victim, it refers to “the Lamb, which was slain from the beginning of the world” (Apocalypse 13:8), the very Lamb who, at Knock here in Ireland, standing in front of the Cross, showed Himself surrounded by the Angels. Saint Thomas says, “This sacrament is called a “hostia” (victim) inasmuch as it contains Christ, Who is a “hostia suavitatis”, that is a sacrificial victim of sweetness, in reference to Ephesians 5:2: “Christ also hath loved us, and hath delivered himself for us, an oblation and a sacrifice to God for an odour of sweetness” (Summa III, q. 73, art. 4).

Abbot Celestino Maria Colombo (1874–1935), whose eightieth anniversary of death we celebrated on 24 September 2015, spoke of his desire to see monks who would be “sons of the Host for the Host”. Abbot Celestino prophesied the vocation of men in whom the influence and power of the Sacred Host — contemplated, adored, and received — is such that they are “ravished unto the love of things invisible” (Preface of the Mass of Christmas) and so become, with Christ, one single sacrificial offering to the Father.

Adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament carries us along in the same direction as the Mass itself — toward the Kingdom: to the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Ghost. Eucharistic adoration is essentially a prayer of desire, a prayer of hunger, of readiness, and of waiting. It is a response to the “still, small voice” (1 Kings 19:12) of the Holy Ghost inviting us to the Son, and through the Son into the bosom of the Father, and into the glory of the Kingdom.

Like all Christian worship, adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament is a pass–over to the Father, with and through the Son, in the Holy Ghost. “No one comes to the Father, but by me” (Jn 14:6). The monk kneeling in adoration before the tabernacle, or before the Sacred Host exposed in the monstrance, is caught up into the great circular movement of the liturgy: from the Father, through his Son, Jesus Christ, in the Holy Ghost, to the Father.

Every good thing comes to us from the Father, through the mediation of Jesus Christ, by means of the presence in us of the Holy Ghost; and likewise, it is by means of the presence of the Holy Ghost, through the mediation of Jesus Christ, that everything returns to the Father.

Eucharistic adoration, Anthony, is a prayer that desires, prepares, and hastens the advent of the Kingdom of God. The adorer grows in awareness of the dawning fulfillment of the prophecy in the psalm intoned by Jesus from the cross: “The poor shall eat and shall be filled, and they shall praise the Lord those who seek him. . . . All the ends of the earth shall remember, and shall be converted to the Lord; and all the families of the nations shall adore in his sight” (Psalm 21:27-28). Made in this spirit, adoration of the Sacred Host delivers the soul from a narrow preoccupation with self and, stretching it to Catholic dimensions, inflames it with the apostolic zeal of the Heart of Christ. “I came”, says Our Lord, “to cast fire upon the earth; and would that it were already kindled” (Luke 12:49).

“After this I looked, and lo, in heaven an open door! And the first voice, which I heard speaking to me like a trumpet, said, ‘Come up hither’” (Apocalypse 4:1). Adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament is, at once, the open door and the invitation. It is faith’s response to the promise made by Our Lord to the one who conquers: “I will grant to him to sit with me on my throne, as I myself conquered and sat down with my Father on his throne” (cf. Apocalypse 3:21).

Praying before the Blessed Sacrament enclosed in the tabernacle or exposed in the monstrance, the adorer catches a glimpse of the glory that lies “beyond the veil” (Hebrews 6:19). The experience of the saints through the ages attests to this, Anthony. The Most Holy Eucharist is “ a pledge of future glory.” Adoration of the Sacred Host is a way of seeking and of discovering “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God” (2 Corinthians 4:6) in what Saint John Paul II called “the Eucharistic face of Christ”.

At Silverstream, although we have prolonged periods of adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament each day, we reserve exposition of the Sacred Host in the monstrance to Thursdays, to the Octave of Corpus Christi, and to certain solemn festivals of the liturgical year.

Until the late 1970s, Anthony, exposition of the Most Blessed Sacrament in the monstrance was always considered a particularly solemn and festive occasion, a kind of condensed expression of the jubilant feast of “Corpus Christi“. Exposition called for an array of candles, flowers, incense, and sacred ministers. It was considered special — something out of the ordinary — and the occasion of a lavish outpouring of graces for those who would come to adore.

Perpetual adoration neither requires nor presupposes perpetual exposition. Historically, the first religious and monastic congregations vowed to perpetual adoration, practiced it before the Blessed Sacrament concealed in the tabernacle. Such was — and remains today in most monasteries — the custom of the Benedictines of the Perpetual Adoration of the Most Holy Sacrament, founded by Mother Mectilde de Bar in 1653.

Personally, Anthony, I fear that, in many places, a kind of minimalistic approach to exposition of the Most Blessed Sacrament has rendered it altogether too banal. At Silverstream we treat exposition of the Sacred Host as an exceptional privilege, a “feast of faith” for the eyes, and a solemn homage to Our Lord calling for all that we can offer Him: candles, incense, flowers, and song.

This is a very long letter, dear Anthony. I have tried to answer your questions thoroughly. Do pray that we Benedictines of Silverstream may live faithfully the Eucharistic vocation that I have attempted to describe in writing to you.

With my blessing,

Father Prior