To prefer nothing to the love of Christ

CHAPTER IV. What are the Instruments of Good Works

CHAPTER IV. What are the Instruments of Good Works

18 Jan. 19 May. 18 Sept.

In the first place, to love the Lord God with all one’s heart, all one’s soul, and all one’s strength.

2. Then one’s neighbour as oneself.

3. Then not to kill.

4. Not to commit adultery.

5. Not to steal.

6. Not to covet.

7. Not to bear false witness.

8. To honour all men.

9. Not to do to another what one would not have done to oneself.

10. To deny oneself, in order to follow Christ.

11. To chastise the body.

12. Not to seek after delicate living.

13. To love fasting.

14. To relieve the poor.

15. To clothe the naked.

16. To visit the sick.

17. To bury the dead.

18. To help in affliction.

19. To console the sorrowing.

20. To keep aloof from worldly actions.

21. To prefer nothing to the love of Christ.

In the Rule of the Master, from which Saint Benedict borrows so judiciously, the chapter on the abbot is immediately followed by a catechesis on fundamental Christian life. The Rule of the Master is so called because it is presented as a dialogue between a master and his disciple. The disciple asks the master to tell him what is the ars sancta, the holy art that the abbot is to teach his disciples in the monastery. The abbot’s duty is to transmit the tools needed for the ars sancta, that is the Christian life. In the school of Christ that is the monastery, the abbot, holding the place of Christ, acts as the magister. He is bound to teach nothing apart from the pure doctrine of Christ. For this reason, the abbot is the guardian of tradition; his sacred duty is to pass on, in its integrity, what he himself received.

Saint Benedict re–works the catechesis of the Master, tying it more closely to life in the monastery. The Master presents his catechesis as a guide to the Christian life, as a program as suitable for the man living in the world as it is for the monk. He does this for two reasons. First, in presenting the great principles of the Christian life—an orthodox Trinitarian faith, love for the Word of God, attachment to Christ, prayer, the commandments, the eradication of vice, and the practice of virtue—the Master wants to show that the monk is a Christian who has resolved to live his baptismal engagements in all their implications and without compromise. Second, it was not uncommon, at the time, for conversion to the Catholic faith and baptism to coincide with a man’s entrance into the monastery. We have, returned, I think, to similar circumstances today. We will see more men entering the Church and the monastery in close succession. This used to be seen as something ill–advised. Increasingly, men see the monastery as the best possible way to live the Christian life and as a logical consequence of the baptismal renunciation of the world, the flesh, and the devil. One cannot argue with this. For some men the monastery supplies the fulness of liturgical life, instruction, and fraternal support that the parish does not offer.

The instruments of good works are presented in an easily memorised inventory. Some see the catalogue in terms of groups of related instruments. There is a certain intuitive association in the sequence of certain instruments, but I do not think one needs to look for an underlying systematic or thematic plan. I do invite you all to read the corresponding Chapters III, IV, V, and VI in the Rule of the Master. Therein you will find the text that Saint Benedict mined in order to give us his own Chapter IV.

I am especially touched by Chapter IV of the Rule of the Master. The disciple asks, “What are the spiritual tools, with which we can work at the divine art?” The Master answers:

Are they not these? Faith, hope, charity, peace, joy, meekness, humility, obedience, silence; above all things chastity of body, a simple conscience, abstinence, purity, simplicity, benignity, goodness, mercy; before all else piety, temperance, watchfulness, sobriety, justice, equity, truth, friendship, measure, order, and perseverance until the end. (Rule of the Master, Chapter IV)

Saint Benedict, for his part, begins with charity, that is, with the love of God and of one’s neighbour. He places the beginning of the monastic ars sancta in charity. Here, Saint Benedict shows himself a faithful disciple of the Beloved Apostle:

Beloved, let us love one another; love springs from God; no one can love without being born of God, and knowing God. How can the man who has no love have any knowledge of God, since God is love? What has revealed the love of God, where we are concerned, is that he has sent his only-begotten Son into the world, so that we might have life through him.That love resides, not in our shewing any love for God, but in his shewing love for us first, when he sent out his Son to be an atonement for our sins. Beloved, if God has shewn such love to us, we too must love one another. (1 John 4:7–11)

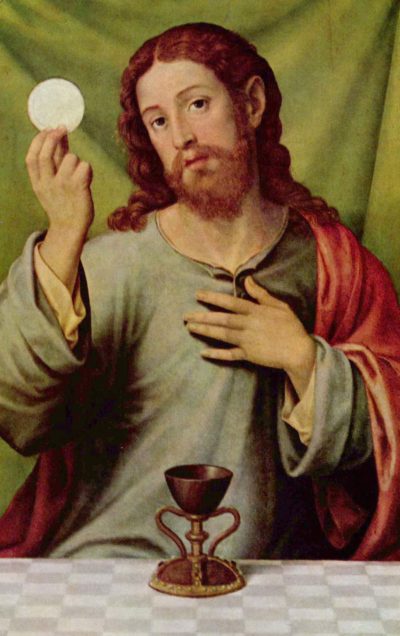

The last instrument in today’s portion is to prefer nothing to the love of Christ. The Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar is the utmost expression of the love of Christ. Saint John introduces the discourse of the Mystic Supper with these words:

Before the paschal feast began, Jesus already knew that the time had come for his passage from this world to the Father. He still loved those who were his own, whom he was leaving in the world, and he would give them the uttermost proof of his love. (John 13:1)

We have the privilege of participating daily in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass: Love’s offering to Love in Love, that is, the Son making Himself over to the Father, as “the pure victim, the holy victim, the spotless victim”, in the sweetness of the Holy Ghost. When we receive the Body of Christ in Holy Communion we are united to Love’s return to Love in Love, that is, to the Son’s return to the Father, in the Holy Ghost. The Body of Christ is given us in fulfillment of the priestly prayer of Christ to the Father:

And I have made known thy name to them, and will make it known; that the love wherewith thou hast loved me, may be in them, and I in them. (John 17:26)

We have moreover the inestimable privilege of living under the same roof as the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. The tabernacle is the abode of love in our midst. It is the new tent of meeting from which it pleases God to hold conversation with man. The privilege of Moses is, by means of the Most Holy Sacrament, extended to all who approach the tabernacle of the Oratory:

And when Moses went forth to the tabernacle, all the people rose up, and every one stood in the door of his pavilion, and they beheld the back of Moses, till he went into the tabernacle. And when he was gone into the tabernacle of the covenant, the pillar of the cloud came down, and stood at the door, and he spoke with Moses. And all saw that the pillar of the cloud stood at the door of the tabernacle. And they stood, and worshipped at the doors of their tents. And the Lord spoke to Moses face to face, as a man is wont to speak to his friend. (Exodus 33:8–11)

To prefer nothing to the love of Christ means to seek Him where is to be found. This is the mystic drama of the Canticle of Canticles that every monk will experience at different moments in his life.

In my bed by night I sought him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, and found him not. I will rise, and will go about the city: in the streets and the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, and I found him not. The watchmen who keep the city, found me: Have you seen him, whom my soul loveth? When I had a little passed by them, I found him whom my soul loveth: I held him: and I will not let him go. (Canticle 3:1–4)

There are, of course, places and situations in which we are certain of coming face–to–face with Christ: in attending to the poor, the naked, the sick, the dead, the afflicted, and the sorrowing members of His Mystical Body, but also in attending to His Eucharistic Body, to the Sacred Host. There a monk approaches the Face of Christ, veiled, yes, but invisibly radiating love and penetrating the heart’s darkest places. Saint Benedict does not mention the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar in presenting the instruments of good works. There is not one of them, however, that is not, in some way, related to the Sacred Host. This is not immediately evident. It is only with the passing years that one comes to understand that, ultimately, the meaning of the monastic life lies in the Sacred Host. All of the instruments of good works have a Eucharistic finality.