Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 19

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

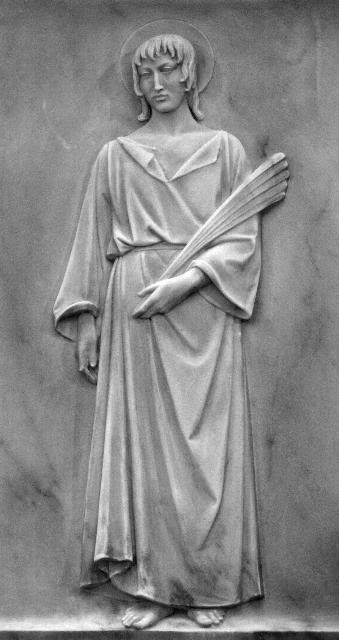

Letter 19: John–Paul

Dear Father,

After thinking about it for about a year, I finally decided to put pen to paper and write you. Although I was born in Ireland, my family immigrated to the U.S. when I was very young. I grew up in something of an Irish enclave in New York, Woodlawn in the Bronx. (Might as well have been Leitrim!) I grew up going back and forth to Ireland and would spend summers with my grandparents in beautiful Kerry. My primary and secondary education was in the local Catholic schools. The local Irish social club had a theatre group in which I became very active. I started helping with various aspects of stage production, then starting playing bit roles and, in the end, I got very much into acting. I did theatre all through college. Currently I do some off–Broadway work. Irish lads seems always to be in demand. It must be the accent. I’m quite capable of turning it on when required! I am a member of the Irish Fraternity of Saint Genesius and find that it is a support to my Catholic identity in the largely heathen world of New York theatre. I wait tables in a café to pay the rent. It’s not the most glamorous job in New York, but the tips are good and I enjoy interacting with the customers.

I enjoy reading your articles on Vultus Christi. You have helped me to sort through my own attraction to the monastic way of life. Funny, isn’t it, that an actor should think of becoming a monk? Stranger things have happened. I visited a Trappist abbey once or twice, a gorgeous place. The monks were very kind. There were days when I thought I could see myself there. I knew Father Ted (seriously, Father Ted!), a Benedictine who was studying music in New York. We had long discussions over coffee on several occasions. Ted told me that his own monastery focused on education and parish work, and that Gregorian Chant had been largely abandoned in favor of a modern English style. Ted told me quite honestly that, unless I wanted to teach or do parish work, he didn’t think his abbey would be my cup of tea.

This leads me to my big question? Would you ever consider allowing the likes of me to spend some time at Silverstream. I know that you have written in the past on Vultus Christi that nothing can replace a real experience of the place and of the life? Also, just to come clean with you . . . I am 34.

Sincerely,

John–Paul

Dear John–Paul,

If you act anything like you write, you must be a great man on stage. I was delighted to read that you belong to the Fraternity of Saint Genesius. The founder and director of the Fraternity, Father John Hogan, is a priest of our diocese and a dear friend of Silverstream. You will have to meet him if you come across to us for a visit. It is not at all odd that an actor should think of becoming a monk. Men come to the cloister from every walk in life. I have known monks who, in the world, were firefighters, police officers, soldiers, postmen, fishermen, barristers, chefs, librarians, teachers, farmers, dancers — yes, old Dom Wilfrid Bayne (1893 – 1974) of Portsmouth, a renowned expert in ecclesiastical heraldry, danced with the Russian Ballet, and Brother Luke (1910–2003) of Mount Saviour was a member of the Boris Volkoff Ballet Group from 1936 to 1942 — psychiatrists, surgeons, social workers, taxi drivers, and Wall Street brokers.

People have a very narrow idea of the sort of men who enter a monastery. They think of one of a number of caricatures and stereotypes: the hardline penitent who wants to atone for the steamy excesses of His youth; the bookish introvert who suffers from terminal social awkwardness; the sacristy rat who is forever holding forth on the cut of chasubles and the only incense suitable for Laetare Sunday; the Plain Chant fanatic who is convinced that outside of Gregorian Chant no one can be saved; the would–be–mystic forever pining after higher things and incompetent in all things earthly. You can dismiss all such caricatures and stereotypes. Monks are like everyone else: complex and not easily put into tidy categories.

All monks, living faithfully in the grace of their profession and consecration, have one thing in common: the surpassing love of Christ. “I live in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and delivered himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). Some men come to the love of Christ directly, in the freshness and purity of an unspoilt childhood. Others come to the love of Christ out of a long loneliness, after having drunk long and deeply of a thousand other loves, all of them disappointing and bitter. Still others come to the love of Christ reluctantly, as to a last recourse, having nowhere else to go. I find a marvelous expression of my own monastic vocation in Psalm 72:

I was all dumbness, I was all ignorance, standing there like a brute beast in thy presence. Yet ever thou art at my side, ever holdest me by my right hand. Thine to guide me with thy counsel, thine to welcome me into glory at last. What else does heaven hold for me, but thyself? What charm for me has earth, here at thy side? What though flesh of mine, heart of mine, should waste away? Still God will be my heart’s stronghold, eternally my inheritance. Lost those others may be, who desert thy cause, lost are all those who break their troth with thee; I know no other content but clinging to God, putting my trust in the Lord, my Master; within the gates of royal Sion I will be the herald of thy praise.(Psalm 72:22–28, Knox translation)

If the charms of this earth leave you empty, John–Paul; if your heart is wasting away with longing for God; if you find happiness in clinging to God and to none other; if you are ready to spend your breath, by day and by night, as the herald of his praise, then perhaps, just perhaps, you may have a monastic vocation.

Life in the monastery is not a short run Off–Broadway. It is a lifelong run, a repetition of the same numbers, a replay of the same routines. Over time, one’s lines get into one’s bones. “Put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh in its concupiscences” (Romans 13:14) One becomes the character one plays while the man one thought one was slowly fades away. “And I live, now not I; but Christ liveth in me” (Galatians 2:20). The theatre exacts a severe discipline; so too does the cloister. A short run production, even if it be tedious, can be endured because the closing is not too far off. A life–long run is another thing entirely. Saint Benedict describes it:

We have, therefore, to establish a school of the Lord’s service, in the setting forth of which we hope to order nothing that is harsh or rigorous. But if anything be somewhat strictly laid down, according to the dictates of sound reason, for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not therefore fly in dismay from the way of salvation, whose beginning cannot but be strait and difficult. But as we go forward in our life and in faith, we shall with hearts enlarged and unspeakable sweetness of love run in the way of God’s commandments; so that never departing from His guidance, but persevering in His teaching in the monastery until death, we may by patience share in the sufferings of Christ, that we may deserve to be partakers of His kingdom.(Rule, Prologue)

If you want to leave the lights of The Big Apple for the obscurity of an obscure little monastery facing the Irish Sea, if you want to live without recognition and without applause, like the Sacred Host silent and hidden in the tabernacle, then perhaps — just perhaps — Silverstream Priory is for you. Do you know the Song of the Suffering Servant in the book of Isaias, John–Paul? The prophet’s mystic script is the height of the Divine Drama; it foretells the Passion of Christ and the abjection of the Host until the end of time. It may speak to your heart.

He will watch this servant of his appear among us, unregarded as brushwood shoot, as a plant in waterless soil; no stateliness here, no majesty, no beauty, as we gaze upon him, to win our hearts. Nay, here is one despised, left out of all human reckoning; bowed with misery, and no stranger to weakness; how should we recognize that face? (Isaias 53:2–3)

Yes, John–Paul, the likes of you is welcome to spend some time at Silverstream. You are 34. If you are going to do it, do it soon. Opening night cannot be put off.

With my blessing,

Father Prior