Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 9

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Letter 9: Wilburt

Dear Father,

First of all, I want to thank you for answering my first letter. Your thoughtful response jolted me into thinking more seriously about a monastic vocation in general, and even about a vocation to Silverstream Priory. Now I must ask you to tell me what exactly you are looking for in a candidate. I have deep–seated fear of not being able to measure up. The monastic vocation seems so sublime, that I wonder if I am not too flawed to even think about it. Would you tell me a little more, Father, of what you are looking for — and not looking for — in a man who aspires to life at Silverstream Priory? Thank you, Father.

Wilburt

Dear Wilburt,

There is nothing better for a man’s soul than a good jolt now and then. It is very easy to fall into the lethargy of routine. One becomes resigned to staying within one’s comfort zone and, for fear of not being able to measure up, one decides, at least subconsciously, to take no more risks. As for your being too flawed to even think about it, there is no flaw so fatal that God cannot turn it into an entry–point of His grace.

For though I should have a mind to glory, I shall not be foolish; for I will say the truth. But I forbear, lest any man should think of me above that which he seeth in me, or any thing he heareth from me. And lest the greatness of the revelations should exalt me, there was given me a sting of my flesh, an angel of Satan, to buffet me. For which thing thrice I besought the Lord, that it might depart from me. And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee; for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful.(2 Corinthiand 12:6–10)

Your flaws endear you to Christ. Where you see a reason for discouragement and a mark of failure, Our Lord sees a reason for mercy and a field for the deployment of His grace. Blessed Abbot Columba Marmion, Ireland’s greatest Benedictine and a potential Doctor of the Church, writes:

It is not our perfection which is to dazzle God, Who is surrounded by myriads of angels; no, it is our misery and wretchedness which draw down His mercy. All God’s dealings with us are a consequence of His mercy (mercy is Goodness touched by the sight of misery), and that is why the great St. Paul says, Let others go to God leaning on the perfection of their life (as the Pharisee), “for me, I take glory in my infirmities that my strength may be His virtue.” If you could once understand that you are never dearer to God, never glorify Him more than when, in the full realization of your misery and unworthiness, you gaze at His infinite goodness and cast yourself on His bosom, believing in faith that His mercy is infinitely greater than your misery. St. Paul tells us that God has done all in laudem et gloriam gratiae suae, “for the praise and glory of His grace.” Now the triumph of His grace is when it raises up the miserable and impure and renders them worthy of divine union.

When, in the Holy Rule, Saint Benedict reviews the qualities needed in a man who comes to be a monk, he would have a senior, one skilled in winning souls, examine, before all else, whether the candidate is truly seeking God (Rule, Chapter 58). While this may seem self-evident, it needs to be said clearly and unambiguously. One comes to be a monk because God alone has become, or is becoming, the one and only desire of one’s heart.

Let a senior, one who is skilled in gaining souls, be appointed over him to watch him with the utmost care, and to see whether he is truly seeking God, and is fervent in the Work of God, in obedience and in humiliations. Let all the hard and rugged paths by which we walk towards God be set before him. (Rule, Chapter 58)

For a Benedictine, the search for God focuses on the adorable Person of Our Lord Jesus Christ or, if you will, on His Face, for Jesus Christ is the Human Face of God.

Philip saith to him: Lord, shew us the Father, and it is enough for us. Jesus saith to him: Have I been so long a time with you; and have you not known me? Philip, he that seeth me seeth the Father also. How sayest thou, shew us the Father? Do you not believe, that I am in the Father, and the Father in me? (John 14:8-10)

For a Benedictine Monk of Perpetual Adoration, this same search leads to the altar, where, concealed in the tabernacle or exposed to our gaze in the monstrance, the Face of Christ, hidden beneath the sacramental veil, is turned toward him, revealing the infinite mercy and loving friendship of His Sacred Heart.

Our little monastery is still something of a start–up operation, Wilburt. Should you come to visit us, you will find nothing of what one would expect to find in an established monastery with a numerous community. The beginnings of a monastery require, not only that a man truly seek God, but also that he be willing to seek Him in the midst of something that is still being built, in the midst of uncertainties, surprises, challenges, and seemingly endless opportunities for self-sacrifice.

Men with a romantic vision of what monastic life ought to be will have to let go of the romantic vision and embrace the real. Our search for God unfolds in the humble, and often challenging, reality of what is here and now. While we do not lose sight of what may develop later on, in God’s good time, we haven’t time to indulge in idealistic daydreaming. God comes to meet us in the real, not in the cherished ideals that we have nurtured of ourselves and by ourselves.

We do not aspire to become a grand abbey. Our aim is to grow to the size of a large extended family, that is between thirty and thirty–five members. A diversity of talents and aptitudes are needed: manual, intellectual, artistic, and technological. If you come to us, be prepared to stretch and be stretched. My own life experience has taught me that monastic obedience often allows a man to discover and develop gifts that he never knew he had.

There are days when our life seems like a series of interruptions. There are always people at the door; Saint Benedict says that they must be welcomed as Christ Himself (cf. Rule, Chapter 53). Things go wrong. Technology fails. In a small community, the horarium (daily time-table) must be adapted and re-adapted to accommodate the human weaknesses of fatigue, illness, and unforeseen demands on time and energy. The readiness to adapt is integral to the Benedictine vision of things. Saint Benedict would have the Abbot be “discrete and moderate . . . so tempering all things that the strong may have something to strive after, and the weak may not fall back in dismay” (Rule, Chapter 64).

In a community still at its beginnings, the monastic journey does not always flow smoothly. There are bumps in our road. There are spiritual potholes. There are detours and wrong turns. For all of this, I can still say with complete confidence that:

Neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor might, nor height nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 8:38-39)

After one’s mid thirties, it is difficult to adapt to monastic life, to submit to the process by which one yields to the demands of life “under a Rule and an Abbot” (Rule, Chapter 1:13). Similarly, men with a previous experience of religious life, find it hard to enter into a new experience with the freshness, sense of wonderment, and discovery that should characterize those taking their first steps in a monastery.

If a man brings with him a cheerful, flexible disposition and the ability to adapt to changes in routine, he will do well with us. If, on the other hand, he is legalistic, all bound up in personal patterns of piety, and incapable of adapting himself to the exigencies of a new foundation, he will not thrive with us. It goes without saying that anyone with a disposition that is chronically critical, judgmental, or arrogant is unfit for monastic life.

If a man brings with him a cheerful, flexible disposition and the ability to adapt to changes in routine, he will do well with us. If, on the other hand, he is legalistic, all bound up in personal patterns of piety, and incapable of adapting himself to the exigencies of a new foundation, he will not thrive with us. It goes without saying that anyone with a disposition that is chronically critical, judgmental, or arrogant is unfit for monastic life.

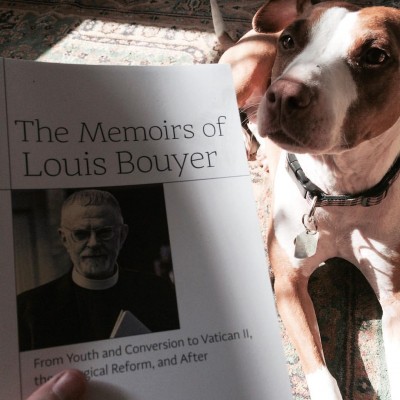

There are other things that you should know. While we cherish our silence and enclosure (separation from the outside world) we are welcoming towards all sorts of people, including families; sometimes families have noisy little children. Saint Benedict says that, “guests, who are never lacking in a monastery, [sometimes] arrive at irregular hours” (Rule, Chapter 53). While we ask our retreatants to observe silence in the guesthouse and on the grounds, we do not expect passing guests or visitors to conform to our monastic disciplines. We also have a gentle dog named Hilda; she often acts in a very doggy fashion. I always keep in mind what Abba Xanthos, one of the desert fathers, wrote: “A dog is better than I am, for he has love and he does not judge”.

With my blessing,

Father Prior