Never to despair of the mercy of God

Meeting the Saints

Meeting the Saints

How and when did Saint Benedict come into my life? He was not among the saints whom I came to know as a small boy in my parish church. Little children readily engage with images. The statues that graced my parish church — I can still see them in my mind’s eye from left to right — were of Saint Anthony of Padua, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Patrick, Our Blessed Lady, the Sacred Heart, Saint Joseph, Saint Thérèse, and Saint Anne. There were five stained glass windows: the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, and the Stigmatization of Saint Francis. These were the images that, at a very early age, drew me into the mysteries of the faith, bringing heaven very close to earth, and making it possible for me to hold conversation with the saints in glory.

Enter Abbot Marmion

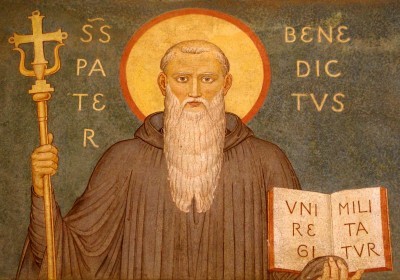

Saint Benedict came into my life when I was about fifteen years old. The monastic ideal had already laid hold of my soul, and my search was well underway. Visiting Saint Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts, I was introduced to Blessed Abbot Marmion’s Christ, the Ideal of the Monk. Heavy reading for a fifteen year old in the torment of the 1960s! I remain grateful to Father Marius Granato for putting Dom Marmion’s classic into my hands, It was in Christ, the Ideal of the Monk that I came to know Saint Benedict in the best way possible: by coming to know his Holy Rule.

Saint Benedict and the Holy Rule

Blessed Abbot Marmion and Saint Benedict joined me on my journey, then, at the same time. I still remember the fire that burned in my heart as I turned the pages of Christ, the Ideal of the Monk, and received the impression of its teaching, like letters engraved on a clean wax tablet. In reading Saint Benedict, as transmitted by Blessed Abbot Marmion, I could almost hear the sound of the Master’s voice. The Rule began to fascinate me and to fashion me. For me, as for Bossuet, it was un mystérieux abrégé de l’Évangile, “a mysterious abridgment of the Gospel”.

Stormy Years

By the time I had turned eighteen — a mere three years later — I had resolved to become a monk, a son of Saint Benedict. These were, of course, frightfully stormy years in the Church: not at all a good time for a young man desirous of engaging with an ideal in all its shining purity. The very things that I thrilled to discover in my reading were, at the same time, being contested and rejected by those to whom they had been given in heritage.

The storms unleashed in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, and by the tumultuous events of 1968, tore through the cloisters of nearly every monastery in North America and, in so doing, tore through the very hearts of those who dwelt in them. One had the impression that nothing was absolute, nothing immutable, nothing sacred. The tyranny of relativism replaced the tyrannies of legalism and rubricism that the reformers decried so bitterly. Things happened and attitudes prevailed that were in no way compatible with the vocation that Thomas Merton had described so eloquently in The Silent Life.

Stranger in Babylon

These years corresponded, as well, with the emergence of various movements of renewal among Catholics. Some of these movements were, as I remember them, rather Protestant in ethos and in sensibility, while others displayed a fascination with all things Eastern. The naive acceptance of certain trends in ecumenism and the indiscriminate reading of Père Teilhard de Chardin, S.J. induced some well–intentioned souls to distance themselves from the sacraments, from the liturgy in all its richness, from the certitudes of objective doctrine, and from devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and to Our Lady. As for me, having found my soul’s true voice in Gregorian Chant as a small boy, and having been nourished from my adolescence on the Divine Office in English, and on Pius Parsch’s The Church’s Year of Grace, the explosion of fashionable “spiritualities” left me feeling like a stranger in Babylon. I was far more interested in the grace that, for me, seeped out of the antiphons at First Vespers of a particular feast than in what one could experience in meditation groups or at prayer meetings. It was all very disconcerting.

The Threshold Once Crossed

At nineteen I had my first experience of Benedictine life, completing a novitiate of two years, wrestling, like Jacob, with angels in the night, and humbled by recurrent health problems. During that time my love for Saint Benedict and the Holy Rule grew exponentially. It was clear, in spite of all the halts and detours, that Saint Benedict had taken me into his family, that he recognized me as his son, and that he would not abandon me.

Gratitude

All these many years later, I can say that Saint Benedict has been a patient companion and loving father through my life. Amidst the choices, changes, and challenges that have marked my route, one phrase from the Holy Rule, the last of the Instruments of Good Works in Chapter IV has kept me on course: Never to despair of the mercy of God. For this alone I am grateful to Saint Benedict and for this I hope to thank him one day in paradise.

A wonderful post, St. Benedict has become a companion of mine, too, as I progress to becoming a Benedictine lay oblate this fall. The Rule has provided me with much inspiration for humility and obedience to God and others in my everyday life.

I, too, am preparing to be received as an Oblate novice. Your story is inspiring and how blessed you were to be drawn so early to monastic life. Thank you for sharing this.