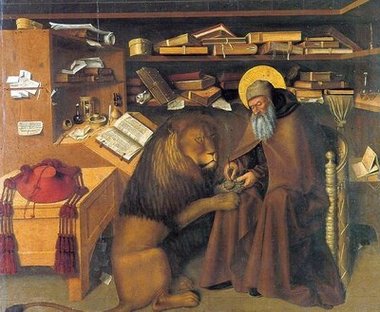

Saint Jerome and Lectio Divina

Jerome, translator of the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible into Latin, the tongue of the common folk, was a lover of the poor Christ. He sang the praises of monastic solitude, saying that “monks do on earth what the angels do in heaven.” We owe to Jerome the theology that sees in monastic profession a kind of second baptism, washing away sin just like martyrdom. It is Jerome who teaches us that the martyrdom of the monastic life is won not by the struggles of continence alone, but by the choice of poverty, and by perseverance in the praise of God.

Jerome was baptized during his student days in Rome. After a first attempt at monastic living in the deserts of Syria, he went to Antioch and there was ordained a priest. With an almost obsessive passion, he devoted himself to the study of Hebrew and Greek. Tutored by none other than Saint Gregory Nazianzen in Constantinople, Jerome went on to Rome where Pope Saint Damasus charged him with the revision of the Latin Bible.

Crankiness and Sanctity

In Rome, Jerome never really got on with other clergy. He was not ambitious for ecclesiastical promotion. He was somewhat irascible, dipping his pen rather more often into vinegar than honey. Jerome loved nothing so much as good squabble, and argued bitterly and at great length with his critics and adversaries. He had little time for trivial niceties.

His Lady Disciples

Jerome’s best friends were women, ladies of the Roman aristocracy whom he had inflamed with his love for Sacred Scripture. These ladies were so devoted to their Jerome that they followed him from Rome to the Holy Land where, in a life of poverty and ceaseless prayer, they studied and learned at his side.

Jerome and Thérèse

The Church’s youngest Doctor, Thérèse, must have been thrilled to meet Jerome in heaven. This, not only because they share the same date of death — Jerome, September 30th, 420, and Thérèse, September 30th, 1897 — but because Thérèse would have been enthusiastic about his Bible study groups for women. In August 1897, a month before her death, Saint Thérèse said, “Regarding Holy Scripture, isn’t it sad to see so many different translations! Had I been a priest, I would have learned Hebrew and Greek, and wouldn’t have been satisfied with Latin. In this way, I would have known the real text dictated by the Holy Spirit” (Last Conversations).

The Word in Your Mouth

Today’s liturgy applies to Jerome a verse from the book of Joshua. “The book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it” (Jos 1:8). “The book shall not depart out of your mouth.” This is the whole significance of meditation in the Bible — not a mental exercise, but a physical one. The Word of God descends into the heart only after being held, and chewed, and savoured at length in the mouth. The biblical understanding of meditation has to do with the material repetition of the text, with learning by heart by saying aloud. Those who read the Scriptures silently deprive themselves of the fundamental experience of the Word of God: hearing it!

Hearing and Doing

Doing of the Word comes after repetition of it. It is not enough to look into the mirror of the Word once, and then go off merrily, expecting to be converted by it. “He who looks into the perfect law, the law of liberty, and perseveres, says Saint James, being no hearer that forgets but a doer that acts, he shall be blessed in his doing” (Jas 1:25). Meditation of the Word is the daily, no, the hourly task of monastics, making the monk, the nun, fruitful in all that he or she does.

The Rejuvenating Word

When you begin to notice leaves withering on a plant, you water the plant. When we begin to notice withering leaves on ourselves, it is urgent that we return, with renewed generosity, to lectio divina. A good drenching in the Word is sometimes all it takes to rejuvenate the soul and send the vital sap of Christ coursing through it. If, after twenty-five, forty, or fifty years of monastic life, you want to end up as the psalm says, “still full of sap, still green” (Ps 92:34), then you must be unswerving, totally committed to your practice of lectio. The Church has no need of withering and withered monastics; she needs fruitful vines, vines that will send out branches and shoots, vines laden with fruit.

Fruitfulness

Holy Doctor Jerome, repeating the Scriptures in his cave in Bethlehem, and Holy Doctor Thérèse in her cell in Carmel simply put into practice the verse of Psalm 1 that, in every age, has been a kind of résumé of claustral perfection, and the secret of monastic fruitfulness. “Blessed is the man whose delight is in the law of the Lord, and on his law he meditates day and night. He is like a tree planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season, and its leaf does not wither” (Ps 1:1-3). Thérèse knew it from Carmel’s ancient Rule of Saint Albert: “Each one of you is to stay in his own cell or nearby, pondering the Lord’s law day and night”(Rule of Saint Albert, 10).

Staying With It

I very much like the emphasis on staying in the cell. Lectio divina requires that we stick with it, that we wrestle with the tough bits, with the passages that seem, at first, impossibly dry and impenetrable. If we leave the cell for a drink of water from any other source — think of Jeremiah’s diatribe against the “broken cisterns that can hold no water” (Jer 2:13) — we risk missing the draught of living water by which God intends to quench our thirst.

One Heart

The Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary was one with the Heart of her Son, and this because Mary had to be in all things the perfect image of the Church. “Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul” (Ac 4:32). If this is true of the early Church described in the book of Acts, it is pre-eminently true of that nucleus of the Church, the community of Jesus and his Mother. The “one-heartedness” of Jesus and Mary proceeds, not from their relationship of flesh and blood, but from Mary’s hearing and keeping of the Word of God. “A woman in the crowd raised her voice and said to him, ‘Blessed is the womb that bore you, and the breasts that you sucked!’ But he said, ‘Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and keep it’” (Lk 11:27-28).

The Cross

This “blessed” in the mouth of Jesus is inextricably linked to the “blessed” of the first psalm. Our own “one-heartedness” with Christ is the fruit of the Word of God repeated “day and night” (Ps 1:2). Don’t expect immediate results. The grace of “one-heartedness” effected by contact with the Word of God is a slow, almost imperceptible process. You will discern it by its fruits, and above all by your response to the mystery of the Cross in your life. The Cross is the consummation of the “one-heartedness” that begins with the hearing of the Word.

A Eucharistic Finality

Mary’s hearing and keeping of the Word led her to the Cross. “Jesus saw his mother, and the disciple whom he loved standing near” (Jn 19:26). Our hearing and keeping of the Word leads us to the actualization of the Cross in the doing of the Eucharist. All lectio divina, be it the corporate lectio of the liturgy, or the solitary lectio of the cell, has a Eucharistic finality. Like our father, Saint Antony of the Desert, we go to church for Holy Mass, repeating the Scriptures on the way. Like Jerome, and like Thérèse–the old Doctor and the new — we long for the “one-heartedness” of the Bridegroom and the Bride, and we find it in the Eucharist, the mystery of communion realized not by flesh and blood, but by the power of the Holy Spirit.

One Word, One Eucharist, One Heart

“Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:17). The one Bread of the Word, broken to feed us, prepares us to partake of the one Divine Bread of the Most Holy Eucharist, broken that we, many though we are, may be of one mind and heart.

Dear Father Prior,

Your words are like finding a signpost together with water in a desert.

~ Jon

Scripture is to be read outloud, to be heard. I don’t think I had really ever pondered that. And yet, “Faith comes by hearing”.

Dear Father Mark,

I very much like the ferocious and learned Jerome.

Your paragraph – “The Word in Your Mouth” – makes me think of Jeremiah 15:16, “Thy words were found and I ate them, and thy words became to me a joy and the delight of my heart”.

Gratefully,

Agnieszka