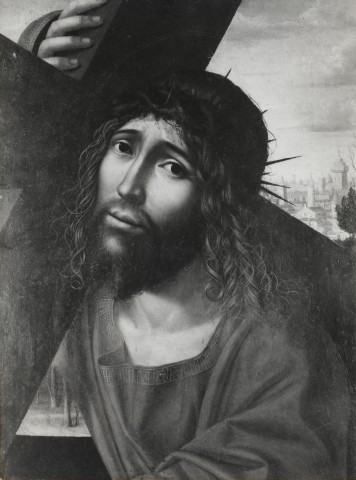

Et quasi absconditus vultus ejus et despectus (VII:7)

CHAPTER VII. Of Humility

4 Feb. 5 June. 5 Oct.

The seventh degree of humility is, that he should not only call himself with his tongue lower and viler than all, but also believe himself in his inmost heart to be so, humbling himself, and saying with the prophet: “I am a worm and no man, the shame of men and the outcast of the people: I have been exalted, and cast down, and confounded.” And again: “It is good for me that Thou hast humbled me, that I may learn Thy commandments.”

Saint Benedict would have his monk live with the mystery of the abjection of Christ, the Suffering Servant, ever before his eyes. He quotes Psalm 21 depicting Our Lord in the humiliations of His Passion: “But I, poor worm, have no manhood left; I am a by-word to all, the laughing-stock of the rabble” (Psalm 21:6). Psalm 21 calls up Isaias’ mysterious prophecy of the Passion of the Lord:

Unregarded as brushwood shoot, as a plant in waterless soil; no stateliness here, no majesty, no beauty, as we gaze upon him, to win our hearts. Nay, here is one despised, left out of all human reckoning; bowed with misery, and no stranger to weakness; how should we recognize that face? How should we take any account of him, a man so despised? Our weakness, and it was he who carried the weight of it, our miseries, and it was he who bore them.

A leper, so we thought of him, a man God had smitten and brought low; and all the while it was for our sins he was wounded, it was guilt of ours crushed him down; on him the punishment fell that brought us peace, by his bruises we were healed.

Strayed sheep all of us, each following his own path; and God laid on his shoulders our guilt, the guilt of us all. A victim? Yet he himself bows to the stroke; no word comes from him. Sheep led away to the slaughter-house, lamb that stands dumb while it is shorn; no word from him. (Isaias 53:1-7)

The monk does does not seek abjection for abjection’s sake; he seeks only Christ, and in finding Christ, he is led into the unfathomable depths of a God who empties Himself out, who, as Saint Paul says, “dispossesses Himself.” One cannot say to the Bridegroom Christ, “Draw me after thee where thou wilt” (Song of Songs 1:3) without being led, step by step, into the mystery of His abjection.

Yours is to be the same mind which Christ Jesus shewed. His nature is, from the first, divine, and yet he did not see, in the rank of Godhead, a prize to be coveted; he dispossessed himself, and took the nature of a slave, fashioned in the likeness of men, and presenting himself to us in human form; and then he lowered his own dignity, accepted an obedience which brought him to death, death on a cross. (Philippians 2:5-8)

The very humility that Christ freely embraced in His Passion perdures in the adorable Sacrament of the Altar. There we find Him dispossessed of Himself, hidden, unrecognized by the multitudes, silent, and covered by the fragile veil of the sacred species. Isaias’ portrayal of the Suffering Servant is mystically fulfilled in the Sacred Host:

Here is one despised, left out of all human reckoning; bowed with misery, and no stranger to weakness; how should we recognise that face? How should we take any account of him, a man so despised? (Isaias 53:3)

A monk who spends much time before the Sacred Host will ineluctably be drawn into the mystery of the divine humility, and into the radiance of the divine countenance “left out of all human reckoning,” hidden and unrecognised. I remember be taken, many years ago, around an immense zone of priestless villages in eastern France. In each of these villages there was a church; in each church, a tabernacle, and in each tabernacle Gesù sacramentato, the hidden Jesus. All around these priestless churches life went on as usual: people buying and sellling, eating and drinking, buying, selling, marrying, planting, and building. The words of Saint John the Baptist came to mind: Medius autem vestrum stetit, quem vos nescitis. “But there is one standing in your midst of whom you know nothing” (John 1:26). The words of Saint John’s Prologue that conclude Holy Mass refer, in some way, not only to the Word made flesh, but also to the Most Holy Sacrament in which the Word made flesh remains among us, the latens Deitas.

He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not. He came unto his own, and his own received him not. (John 1: 10-11)

Fr Prior,

Good to see your Knox Bible getting some use!;-)

~ Br Melchesidech