Peering Through the Windows

Collect

Almighty and everlasting God,

who for the defence of the veneration of sacred images,

didst endue blessed John with heavenly doctrine

and wonderful strength of spirit:

grant unto us by his intercession and example,

that we may imitate the virtues and experience the protection

of those whose images we venerate.

Secret

May the gifts we offer be rendered worthy in thy sight

through the loving advocacy of blessed John

and of the Saints whose images, by his labour,

are exposed for veneration in our temples.

Postcommunion

We beseech Thee, O Lord, that the gifts of which we have partaken

may shield us with heavenly armour,

and may the advocacy of blessed John,

together with the prayers of the Saints,

the veneration of whose images

he victoriously upheld in the Church,

plead with one voice on our behalf.

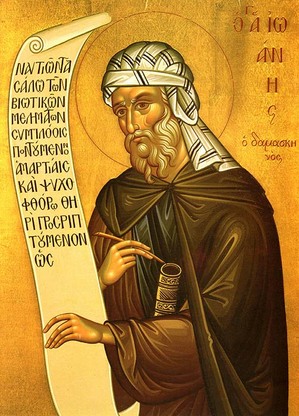

Saint John Damascene, Champion of the Veneration of Icons

The feast of Saint John Damascene reminds us of the place of sacred images in the Christian life. I cannot conceive of a Christian life devoid of images. How bleak our churches would be, how dreary our homes, our empty our rooms without the blessed sacramentals that are the images of Our Lord, of Our Lady, of the Angels, and of the Saints!

Saint Barbara

Saint Barbara, Virgin and Martyr, who shares this date with Saint John Damascene, was imprisoned in a tower by her father until she should renounce Christ. Barbara, taking advantage of her father’s absence, summoned the servants and directed them to pierce three windows in her tower prison, so that, through three windows, One Single Light might shine in her solitude: an image of the Adorable and Undivided Trinity. In her own way, Saint Barbara fashioned an image of the Most Holy Trinity, one that only the eyes of faith could recognize.

A Company of Friends

Even in prisons, Christians, suffering for the faith, are known to etch a cross or sacred image on a wall, or to fashion objects of piety from the limited materials at hand. Sacred images preserve us from the existential loneliness that would have us think that, in all the universe, there is no one looking after us, no one caring for us, no one interceding for us. A sacred image is an invitation to peer into heaven, all the while receiving the reflection of the Deifying Light. The images of the saints remind us that we have “so great a cloud of witnesses over our head” (Heb 12:1), and that we are surrounded by company of friends, all of whom take the liveliest interest in our journey through this vale of tears.

There is something sad and cold about a church devoid of sacred images. If a church is a representation of heaven on earth, how can it not be populated with images of those whose voices are one with ours in adoring, praising, thanking, and pleading before the throne of God and of the Lamb?

A Diabolical Revolt

The iconclasm that ravaged so many churches in the wake of the Second Vatican Council was, at the core, a diabolical revolt against the whole sacramental economy of the Incarnation. It will take creative vision and courage to reclaim such churches for things heavenly, to re-order sanctuaries, and restore what was, in effect, stolen from Christ’s faithful.

Many of those responsible for the so-called renovation of churches over the past fifty years took their models from an angst-ridden, post-World War II, northern European, liberal Protestant sensibility. They dismissed the noble traditions of the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the joyful exuberance of the Catholic Baroque, and the magnificent Spanish Colonial imagery that flourished in Latin America. How often did I hear (especially in France) that one wanted things to be sober, simple, and dépouillé . . . by that, understand dull, uninspiring, and bleak. The sanctuary itself had to be indistinguishable from the “place of the assembly”; the tabernacle was relegated to a place of insignificance, and all honour paid to the “presider’s chair.” Enough.

Churches resembling vast empty warehouses, athletic centres, or meeting halls effectively extinguish the flame of the orthodox catholic faith because, they constitute an affront to the mystery of the Incarnation and to the whole sacramental economy that flows from it. They invite to the building of a social order deformed and stunted by secular humanism, to the tired and moribond values of the French Revolution and of the Enlightenment; they obscure any glimpse of the glory that is promised us and that reaches our souls, even now, filtered through the complexus of sacred signs that constitutes the liturgy.

In the Monastery

I’ve not counted the number of sacred images that grace this little monastery. There are a multitude of them: the Holy Face of Jesus in several places, the Child Jesus in my cell and in the library, the Mother of God in every room, Saint Joseph in the entrance hall, Saint Benedict in the oratory, Saints John and Benedict in the sacristy . . . and there are more. Each one is an invitation to communion with Our Lord Jesus Christ, with the Mother of God and with all the Saints. In an environment of faith, it is well nigh impossible to see a sacred image and not raise one’s heart and mind to God. How many acts of love, how many aspirations of hope, of adoration, and of faith are generated by the sight of sacred images!

As Through a Window

A sacred image is a window through which the inhabitants of the heavenly Jerusalem peer into the times and spaces of our lives. It is, at the same time, a window through which, we are given a glimpse, however fleeting and obscure, of “what things God hath prepared for those that love him.” (1 Cor 2:9) Who would not want to stand before such a window?