Contemplation of the Glorious Face of Christ

In yesterday’s general audience, our extraordinarily “Benedictine” Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, presented the figure of Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny. For the nascent Monastery of Our Lady of the Cenacle, this teaching represents a foundational element. Pope Benedict XVI is, in a very real way, the father of our little monastery. The translation appeared on Zenit.

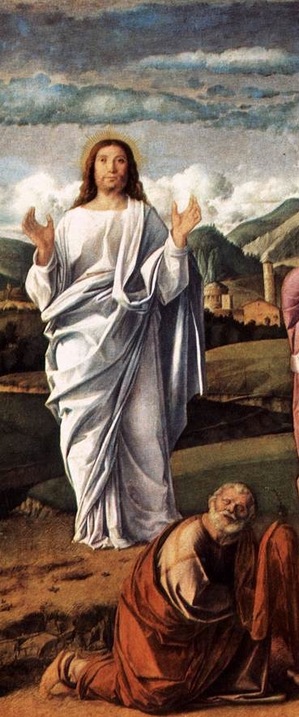

The characteristic theological piety of Peter and of the Cluniac Order: wholly set to the contemplation of the glorious face (gloriosa facies) of Christ, finding there the reasons for that ardent joy that marked his spirit and was radiated in the liturgy of the monastery.

The Beauty of the Liturgy

Dear brothers and sisters,

The figure of Peter the Venerable, which I wish to present in today’s catechesis, takes us back to the famous abbey of Cluny, to its “decorum” (decor) and its “lucidity” (nitor), to use terms that recur in the Cluniac texts — decorum and splendor– which are admired above all in the beauty of the liturgy, the privileged path to reach God.

Holiness

Even more than these aspects, however, Peter’s personality recalls the holiness of the great Cluniac abbots: At Cluny “there was not a single abbot who was not a saint,” said Pope Gregory VII in 1080. Among these is Peter the Venerable, who to some degree gathers in himself all the virtues of his predecessors — although already with him, Cluny, faced with new orders such as that of Citeaux, began to experience symptoms of crisis.

Peace

Born around 1094 in the French region of Auvergne, he entered as a child in the monastery of Sauxillanges, where he became a professed monk and then prior. He was elected abbot of Cluny in 1122, and remained in this office until his death, which occurred on Christmas Day, 1156, as he had wished. “Lover of peace,” wrote his biographer, Rudolph, “he obtained peace in the glory of God on the day of peace” (Vita, I, 17; PL 189, 28).

The Habit of Forgiving

All those who knew him praised his elegant meekness, serene balance, self-control, correctness, loyalty, lucidity and special attitude in mediating. “It is in my very nature,” he wrote, “to be somewhat led to indulgence; I am incited to this by my habit of forgiving. I am used to enduring and forgiving” (Ep. 192, in: “The Letters of Peter the Venerable,” Harvard University Press, 1967, p. 446).

Happy With His Lot

He also said: “With those who hate peace we wish, possibly, to always be peaceful” (Ep. 100, 1.c., p. 261). And of himself, he wrote: “I am not one of those who is not happy with his lot … whose spirit is always anxious and doubtful, and who laments that all the others are resting and he alone is working” (Ep. 182, p. 425).

Gracious and Affectionate

Of a sensitive and affectionate nature, he was able to combine love of the Lord with tenderness toward his family, particularly his mother, and his friends. He was a cultivator of friendship, especially in his meetings with his monks, who usually confided in him, certain of being received and understood. According to the testimony of his biographer, “he did not disregard or refuse anyone” (Vita, 1,3: PL 189,19); “he seemed gracious to all; in his innate goodness, he was open to all” (ibid., I,1: PL, 189, 17).

Tolerance

We could say that this holy abbot is an example also for the monks and Christians of our time, marked by a frenetic rhythm of life, where incidents of intolerance and lack of communication, division and conflicts are not rare. His witness invites us to be able to combine love of God with love of neighbor, and never tire of renewing relations of fraternity and reconciliation. In this way, in fact, Peter the Venerable behaved, finding himself guiding the monastery of Cluny in years that were not very tranquil for several external and internal reasons, succeeding in being simultaneously severe and gifted with profound humanity. He used to say: “You will be able to obtain more from a man by tolerating him, than by irritating him with complaints” (Ep. 172, 1.c., 409).

In the Midst of Many Cares

Because of his office, he had to make frequent trips to Italy, England, Germany and Spain. Forced abandonment of contemplative stillness weighed on him. He confessed: “I go from one place to another, I am anxious, disturbed, tormented, dragged here and there; my mind is turned now to my affairs, now to those of others, not without great agitation to my spirit” (Ep. 91, 1.c., p. 233). Although having to maneuver between the powers and lordships that surrounded Cluny, nevertheless, thanks to his sense of measure, his magnanimity and his realism, he succeeded in keeping his habitual tranquility. Among the personalities with whom he interacted was Bernard of Clairvaux, with whom he enjoyed a relationship of growing friendship, despite differences of temperament and perspectives. Bernard described him as an “important man, occupied in important affairs” and he greatly esteemed him (Ep. 147, ed. Scriptorium Claravallense, Milan, 1986, VI/1, pp. 658-660), whereas Peter the Venerable described Bernard as “lamp of the Church” (Ep. 164, p. 396), “strong and splendid column of the monastic order and of the whole Church” (Ep. 175, p. 418).

The Wounds of the Body of Christ

With a lively ecclesial sense, Peter the Venerable said that the affairs of Christian people should be felt in the “depth of the heart” of those who number themselves “among the members of the Body of Christ” (Ep. 164, 1.c., p. 397). And he added: “He is not nourished by Christ who does not feel the wounds of the Body of Christ,” wherever these are produced (ibid.). Moreover, he showed care and solicitude even for those who were outside the Church, in particular for the Jews and Muslims: to foster knowledge of the latter he had the Quran translated. In this regard, a recent historian observed: “Amid the intransigence of the men of Medieval times, also among the greatest of them, we admire here a sublime example of the delicacy to which Christian charity leads” (J. Leclercq, Pietro il Venerabile, Jaca Book, 1991, p. 189).

Love of the Eucharist and of the Virgin Mary

Other aspects of Christian life dear to him were love of the Eucharist and devotion to the Virgin Mary. On the Most Holy Sacrament he has left us pages that are “one of the masterpieces of Eucharistic literature of all times” (ibid., p. 267), and on the Mother of God he wrote illuminating reflections, always contemplating her in close relationship with Jesus the Redeemer and his work of salvation. Suffice it to report this inspired elevation of his: “Hail, Blessed Virgin, who put malediction to flight. Hail, Mother of the Most High, spouse of the most meek Lamb. You conquered the serpent, you have crushed his head, when the God generated by you annihilated him … Shining star of the East, who puts to flight the shadows of the West. Dawn that precedes the sun, day that ignores the night … Pray to God born from you, so that he will absolve us from our sin and, after forgiveness, grant us grace and glory” (Carmina, Pl 189, 1018-1019).

The Radiant Face of Christ

Peter the Venerable also nourished a predilection for literary activity and he had the talent. He wrote down his reflections, persuaded of the importance of using the pen almost like a plough “to scatter on paper the seed of the Word” (Ep. 20, p. 38). Although he was not a systematic theologian, he was a great researcher of the mystery of God. His theology sinks its roots in prayer, especially the liturgy, and among the mysteries of Christ he favored the Transfiguration, in which the Resurrection is already prefigured. It was in fact he who introduced this feast at Cluny, composing a special office for it, in which is reflected the characteristic theological piety of Peter and of the Cluniac Order, wholly set to the contemplation of the glorious face (gloriosa facies) of Christ, finding there the reasons for that ardent joy that marked his spirit and was radiated in the liturgy of the monastery.

Adhering Tenaciously to Christ

Dear brothers and sisters, this holy monk is certainly a great example of monastic sanctity, nourished at the sources of the Benedictine tradition. For him, the ideal of the monk consisted in “adhering tenaciously to Christ” (Ep. 53, 1.c., p. 161), in a cloistered life marked by “monastic humility” (ibid.) and industriousness (Ep. 77, 1.c., p. 211), as well as by a climate of silent contemplation and constant praise of God. According to Peter of Cluny, the first and most important occupation of a monk is the solemn celebration of the Divine Office –“heavenly work and of all the most useful” (Statuta, I, 1026) — to be supported with reading, meditation, personal prayer and penance observed with discretion (cf. Ep. 20, 1.c., p. 40).

The Ideal of the Monk and of Every Christian

In this way the whole of life is pervaded by profound love of God and love of others, a love that is expressed in sincere openness to one’s neighbor, in forgiveness and in the pursuit of peace. By way of conclusion, we could say that if this style of life joined to daily work is, for St. Benedict, the ideal of the monk, it also concerns all of us; it can be, to a great extent, the style of life of the Christian who wants to become a genuine disciple of Christ, characterized in fact by tenacious adherence to him, by humility, by industriousness and the capacity to forgive, and by peace.

[Translation by ZENIT]

I believe that this is not the first time that Pope Benedict XVI has spoken eloquently on the beauty of the monastic vocation. Did he not touch upon this subject also during his visit to Paris?

Although married with children, I have always held the monastic ideal in the highest regard and have been known to become quite indignant when I hear monasticism denigrated by worldly modern Catholics.