Do all things with counsel

17 Jan. 18 May. 17 Sept.

Let all therefore, follow the Rule in all things as their guide, and let no man rashly depart from it. Let no one in the monastery follow the will of his own heart: nor let any one presume insolently to contend with his Abbot, either within or without the monastery. But if he should so presume, let him be subjected to the discipline appointed by the Rule. The Abbot himself, however, must do everything with the fear of God and in observance of the Rule: knowing that he will have without doubt to render to God, the most just Judge, an account of all his judgments. If it happen that less important matters have to be transacted for the good of the monastery, let him take counsel with the Seniors only, as it is written: “Do all things with counsel, and thou shalt not afterwards repent it.”

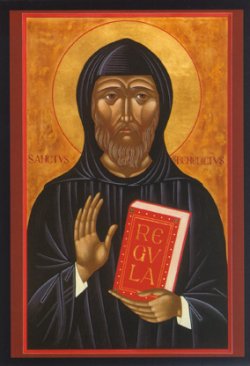

Saint Benedict eschews rashness and excess. He would have his monks exercise discretion in all things, following the teaching of Cassian:

Judgment and discretion, passing by excess on either side, teach a monk always to walk along the royal road, and do not suffer him to be puffed up on the right hand of virtue, that is, from excess of zeal to transgress the bounds of due moderation in foolish presumption, nor allow him to be enamoured of slackness and turn aside to the vices on the left hand, that is, under pretext of controlling the body, to grow slack with the opposite spirit of luke-warmness. (Cassian, Conferences 2, Chapter 2)

Inevitably, the monk who follows the will of his own heart, especially in ascetical and spiritual matters, will fall into some exaggeration: either a neurotic scrupulosity on the one hand or into a delusional laxity on the other. In the chapter Of the Observance of Lent, Saint Benedict indicates that the monk who takes on acts of piety or penance without the blessing of the abbot, thereby forfeits all reward from God, because instead of humbling himself and submitting his judgment to the abbot, he is indulging his self–will.

Let each one, however, make known to his Abbot what he offereth, and let it be done with his blessing and permission: because what is done without leave of the spiritual father shall be imputed to presumption and vain-glory, and merit no reward. Everything, therefore, is to be done with the approval of the Abbot. (Chapter XLIX)

The monk who indulges his self–will in little things—especially in acts of piety, in particular penances, or in reading what he chooses—will inevitably come into conflict with his abbot over greater things. Such a monk, corrupted by vainglory and deceived by pride, risks even contending with his abbot in a public outburst. Such a brother will have to be subjected to the discipline of the rule.

Saint Benedict is realistic about the abbot. He knows well that abbots have feet of clay, that they too are men beset with weakesses. For this reason he issues a warning to the abbot who, like all mortals, will have to appear one day before the dread Judgment Seat of God and there account for his decisions:

The Abbot himself, however, must do everything with the fear of God and in observance of the Rule: knowing that he will have without doubt to render to God, the most just Judge, an account of all his judgments.

The abbot must repeat to himself continually the words of Saint Paul:

And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee: for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful. (2 Corinthians 12:9–10)

At the end of the chapter, Saint Benedict speaks of the council of the seniors. This would not have been a juridically constituted body but, rather, a circle of fathers, recommended by their age in religion, or by their virtue, or by their competence in a particular field. They may also be the same fathers whom, on occasion, the abbot sends as emissaries of mercy to bring back the lost sheep, to lift up the fallen, and to console wavering brothers (Chapter XXVII). The abbot who, before acting, consults fathers of mature years and wisdom, demonstrates humility and prudence. He ought moreover to ask for the prayers of these same fathers whenever he stands in need of light from above, for, as Saint James says, “The continual prayer of a just man availeth much” (James 5:16).