Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 1

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Letter I: Wilburt

Dear Father,

I have, for some time, been thinking that I may be called to monastic life. What frightens me is the commitment to live and die in one place. I have thought of Silverstream Priory: the spirit of your community is appealing, but the Irish climate is off–putting. I have thought of Winkleshore Abbey: the men there are heroic, but the monastery is too isolated. I considered Stillbrook Abbey: everything is impeccable at Stillbrook, but I’m told the summer heat there is suffocating and the mosquitoes voracious. I even considered the Italian monastery of Monte Muto: the setting is glorious, but I don’t think I could adjust to the diet there or to speaking Italian all the time. I have even thought of entering the abbaye of Grand–Vent; the chant of the monks there is heavenly, but I don’t think I’m capable of measuring up to French standards of correctness. How can I be sure of choosing the right community? What if I discover that I cannot adjust to the climate, or to the food, or to or the other men in the community? I have visited several monasteries. Each one appeals to me in a different way, but I am afraid to make a choice. Time is running out and I feel paralysed by indecision. Can you give me any counsel?

Wilburt

Dear Wilburt,

The perfect monastery exists nowhere on the globe. The perfect climate exists nowhere on the globe. It is true that in Ireland the winters are long, damp, cold, and gloomy. It is also true that Irish springs and autumns are lovely, even if the Irish summer is very short. Wherever one goes there will be some kind of discomfort.

The sun riseth, and goeth down, and returneth to his place: and there rising again, maketh his round by the south, and turneth again to the north: the spirit goeth forward surveying all places round about, and returneth to his circuits. All the rivers run into the sea, yet the sea doth not overflow: unto the place from whence the rivers come, they return, to flow again. All things are hard: man cannot explain them by word. The eye is not filled with seeing, neither is the ear filled with hearing. What is it that hath been? the same thing that shall be. What is it that hath been done? the same that shall be done. Nothing under the sun is new, neither is any man able to say: Behold this is new: for it hath already gone before in the ages that were before us. (Ecclesiastes 1: 5–10)

Even in the “right” community, once the initial romance wears away, you will, over time, discover a hundred things that, in your eyes, are wrong, or defective, or wanting. In Chapter 72 of the Holy Rule, Saint Benedict says: “Let them most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of mind”. After a few months in the monastery, you will begin to see the failings of the men with whom you live. You will be tempted to criticize, to pass judgment, to murmur against them saying, “Alas, even here the salt has lost its savour. The observance is not what I thought it would be. Father X is lazy. Father Y talks too much. Father Z is too fond of his food and drink”. Young idealists are easily scandalised by the weaknesses they see all around them. My experience is this: where weaknesses abound, the grace of Christ super–abounds. Our Lord is not repelled by our weaknesses; He is irresistibly drawn to those who, acknowledging their weaknesses, trust in His grace.

For myself I will glory nothing, but in my infirmities. For though I should have a mind to glory, I shall not be foolish; for I will say the truth. But I forbear, lest any man should think of me above that which he seeth in me, or any thing he heareth from me. And lest the greatness of the revelations should exalt me, there was given me a sting of my flesh, an angel of Satan, to buffet me. For which thing thrice I besought the Lord, that it might depart from me. And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee; for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful. (2 Corinthians 12:5–1o)

The holiest monks remain, even to the end, fragile earthen vessels. One by one, the pedestals upon which you exalted them in your imagination will crumble into dust. The same thing happens in the best of marriages. Every crisis is an opportunity to cry out to the Lord with confidence and to open wide to the power of grace.

Who then shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation? or distress? or famine? or nakedness? or danger? or persecution? or the sword? (As it is written: For thy sake we are put to death all the day long. We are accounted as sheep for the slaughter.) But in all these things we overcome, because of him that hath loved us. For I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor might, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:35–39)

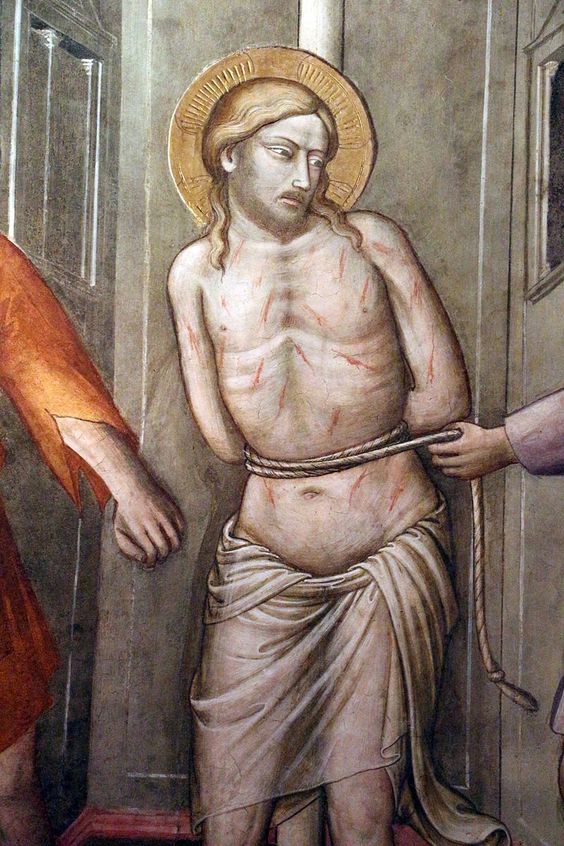

Wherever a man enters monastic life, he will, sooner or later, be faced with the mystery of the Cross. One comes to the monastery to seek God, but no man can seek God without dying to himself. The Lord said to Moses, “Thou canst not see my face: for man shall not see me and live” (Genesis 33:30). For some, death comes at the end of a fierce concentrated combat; for others it is prolonged over many years. One thing is certain: there is no authentic monastic life without a real participation in the mystery of the Cross. Every true vocation is marked indelibly with the sign of the Cross, and where the Cross is, there too is life, and light, and fruitfulness beyond all human measuring.

God, who commanded the light to shine out of darkness, hath shined in our hearts, to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God, in the face of Christ Jesus. But we have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellency may be of the power of God, and not of us. In all things we suffer tribulation, but are not distressed; we are straitened, but are not destitute; we suffer persecution, but are not forsaken; we are cast down, but we perish not: always bearing about in our body the mortification of Jesus, that the life also of Jesus may be made manifest in our bodies. For we who live are always delivered unto death for Jesus’ sake; that the life also of Jesus may be made manifest in our mortal flesh. (2 Corinthians 4:6–11)

The real tragedy, dear Wilburt, is when men set their hopes on an ideal, perfect monastery that does not exist, and not finding it anywhere, pass from one place to another until they are too old to renounce themselves and submit to a monastic discipline anywhere. Every vocation, even if it be to a monastery in one’s own native county, includes the word of the Lord to Abram:

Go forth out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and out of thy father’ s house, and come into the land which I shall shew thee. (Genesis 12:1)

I send you my blessing, Wilburt, and assure of my prayers and of the prayers of the brethren here.

Father Prior