The Living Icons in the Holy Rule of Saint Benedict

Christo Omnino Nihil Praeponant: To Prefer Nothing to Christ

Each Person is an Image of Christ

Jesus said to them, “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” They said, “Caesar’s.” Then He said to them, “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” (Mt 22:20-21)

This is a passage from last Sunday’s Gospel for the Twenty-second Sunday after Pentecost. Jesus has been put in a trap by His questioners over a matter of paying tribute to the oppressive secular power. He escapes the trap by not only answering the question but teaching an even more important lesson. Invoking the likeness (imago) imprinted on the coin, he shows that the coin is for paying tribute to Caesar because it is made in Caesar’s image whereas human nature is made in the image of God (Gen 1:27), and thus we must render to God “the things that are God’s”. Many lessons could be drawn out of this marvellous response, however, if we focus on the imago Dei drawn out of this passage, we will see that just as the little coin is an “icon” of Caesar, each person is a living icon of Christ.

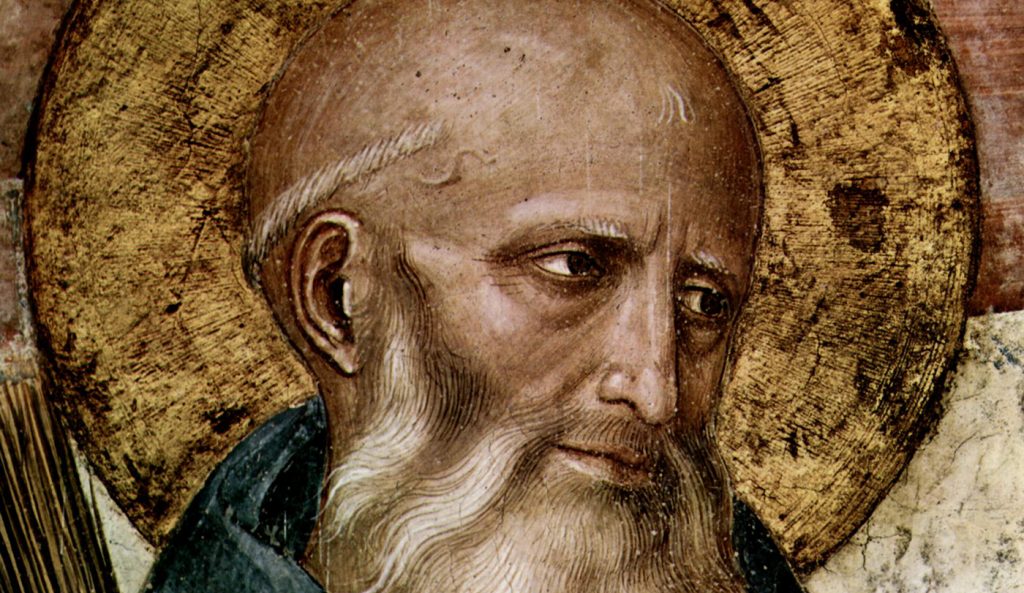

Turning to Saint Benedict

To do this, we can turn to our Father Saint Benedict to study the various images or representations of Christ in his Holy Rule. Through this we will discover that human beings, made in the image of God and restored to grace by the Incarnation, are living Icons of Christ. This is beautifully illustrated by Saint Benedict in the examples he gives of the various people who represent Christ.

The Representations of Christ in the Holy Rule

In the Holy Rule of Saint Benedict, there are several significant places where particular persons are referred to as representing Christ or holding His place. In examining three examples of the Abbot, the sick brethren, and the guests, the parallels to the theology of iconography will be apparent in both the fact that they represent a sort of image or depiction of Christ and the fact that we are to venerate them on account of Christ Whom they represent.

The Abbot

The Holy Rule, Chapter 5, About Obedience

As soon as there is some command of a superior, they [the monks] know no more delay in doing it than were it divinely commanded. Of these does the Lord say: At the hearing of the ear hath he obeyed Me, (Ps 17:44) and again to teachers He says: Who heareth you heareth Me. (Lk 10:16)

Here in his chapter on obedience, Saint Benedict quotes two Scripture verses. One is from the Psalms which are placed mystically on the lips of Jesus, and the other is a word from the Gospel of our Lord Himself. In both cases, Saint Benedict is showing that the superior is acting in the person of Christ. In the first Scripture reference, in line with patristic tradition, Saint Benedict interprets the Psalms as being the words of Christ. Saint Benedict describes the disciple who obeys as doing so because he has really heard Him Who is to be obeyed. And how the disciple hears Christ is described in the second Scripture passage: he hears through hearing the Abbot who represents Him. The disciple monk who obeys is hearing and obeying Christ; obedience given to the Abbot is given to Christ, for he holds “the place of Christ.” (From Chapter 63) The Abbot then is seen as a living embodiment of Christ’s authority and paternity.

Chapter 63: About the Order of the Community

Saint Benedict goes on to say that the Abbot:

should be called lord and Abba, not by assuming it himself, but for the honour and love of Christ. And let him reflect and exhibit himself in such a way as to be worthy of such an honour.

This living embodiment of Christ that the Abbot is, then, is not just an institutional office but a sacred role imbued with divine responsibility. The abbot’s actions, words, and decisions are meant to reflect the will of Christ. Further, Saint Benedict is even saying that, not only through obedience but even in how he is addressed, the Abbot ought to be reverenced with a certain veneration that is given to Christ.

The Sick

Chapter 36: About Infirm Brethren

Saint Benedict devotes a whole chapter of the Holy Rule to ensure that the utmost solicitude is given to the sick brethren. He begins the chapter thus:

Care for the infirm must be kept above all and before all that they may be so served as if actually Christ. For He said: I was infirm and thou didst visit Me; (Matt 25:36) and, What thou didst to one of these least, thou didst to Me. (Matt 25:40)

Saint Benedict again draws on the words of the Lord in the Gospel, this time twice quoting the parable of the sheep and the goats. Here again, this solicitude is shown because the guests are a representation of Christ. Using our Lord’s own words, Saint Benedict shows that the sick brothers represent Christ through their very infirmities. As Christ took on a human nature subject to infirmities, especially those infirmities displayed in His suffering of the passion, the infirm brothers make visible the weakness and vulnerability of His Human nature. They are an image of Him undergoing His passion.

Saint Benedict goes on to prescribe the infirmary, a “cell specially appointed”, and an infirmarian, a “server, God-fearing and loving and solicitous”, for the service of the sick brothers. The infirmarian must be God-fearing so as to understand the significance of his task and what it symbolises. In prescribing the care and solicitude in the community’s service toward the sick, Saint Benedict is acknowledging a certain veneration due to them based on the fact that Christ is mystically present in them.

Guests and Visitors

Chapter 53: About Guests

There is a long tradition of hospitality in monasticism both in the East and in the West, and in this Saint Benedict standing in a continuous tradition going back to the desert fathers. Saint Benedict holds up as an image of Christ even the guests and visitors who come to the monastery:

All the guests that arrive should be received as Christ, because He it is who is to say: I was a guest and you received Me, (Matt 25:36) and let fitting honour be shown to all, especially to those of the household of faith and to pilgrims.

Again, Saint Benedict employs the parable of the sheep and goats, this time as a lens for seeing the image of Christ in the guests. In the stranger, Christ is again shown in His humility and unexpected littleness, for the admonition, “What thou didst to one of these least, thou didst to Me”, still applies, and this is made explicit by Saint Benedict when he goes on to say, “Care most especially should be shown with all solicitude in receiving poor and pilgrim people, for in them is Christ received in a greater degree.” In other words, if a visitor is a great benefactor and friend or another noble person who already receives honour, then for Saint Benedict it is to a lesser degree that he is holding the place of Christ, Who is more perfectly represented in the poor and the stranger. Christ Himself came into the world as a poor infant and sojourned in His childhood in a strange land (Mt 2:13) and was not recognised for Who He really was during His public ministry (Jn 6:42).

As to what honour is owed Christ in His representatives, the guests, Saint Benedict gives an injunction with a somewhat surprising intensity: “with head inclined, or even whole body prostrate on the ground, let Christ be adored in them, Who is also the One received.” Taken apart from the theology of iconography, we would be worshipping the guests! Obviously, Saint Benedict is not asking that the guests themselves be adored but claiming that the veneration given to the guests passes on to a real worship or adoration of Christ Who is depicted.

As with the infirm an infirmarian is assigned, so with the guests a guest master must be assigned whose “soul is possessed of the fear of God” for much the same reasons for which that of the infirmarian must be. The work of hospitality, then, like the service of the sick brethren, is a sacred work in which the service rendered is a veneration that passes one to the One depicted. All partake in this action, since if Christ comes in the person of the Guest no one should be excluded from the opportunity to receive Him. Thus does Saint Benedict say that “both the Abba and the whole community are to wash feet for all the guests, and when they have been washed let them say this verse: We have received, O God, Thy mercy in the midst of Thy temple.”(Ps 47:10) Upon venerating the guests, the Abbot and community give thanks for the great mercy of Christ’s presence among them.

A Sacramental Reality

If we look again at the parable of the sheep and goats, it is important to remember that the context of this and two other parables is our Lord’s eschatological discourse. (Mt 24-25) Saint Benedict seems to feel a certain urgency to fulfil these injunctions of our Lord because he takes seriously the fact that the monk’s participation in the Age to Come will depend on it. And so, Saint Benedict says in the future indicative: “He it is Who will say” (ipse dicturus est). There is a sense that the reality of Christ is made immediately present by this representative symbolism in the Abbot, the sick brethren, and the guests.

The significance of this points to a sacramental view of reality in which all created things make present what they signify in a real participatory way. If the monk is one who is truly seeking God (Chapter 58), then he will not fail to seek His presence in the living icons which are present to him in his monastic life.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)