The loving example of the Good Shepherd (XXVII:2 and XXVIII)

CHAPTER XXVII. How careful the Abbot should be of the Excommunicate

4 Mar. 4 July. 3 Nov.

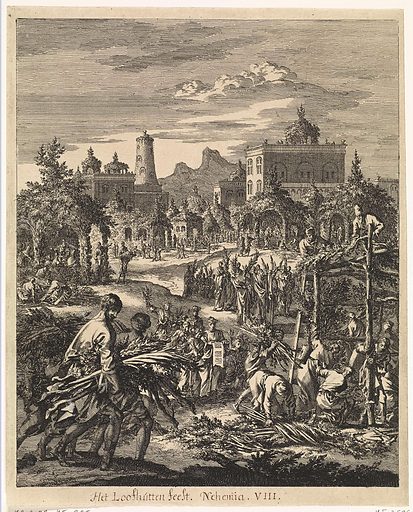

For the Abbot is bound to use the greatest care, and to strive with all possible prudence and zeal, not to lose any one of the sheep committed to him. He must know that he hath undertaken the charge of weakly souls, and not a tyranny over the strong; and let him fear the threat of the prophet, through whom God saith: “What ye saw to be fat that ye took to yourselves, and what was diseased ye cast away” (Ezechiel 34:3–4). Let him imitate the loving example of the Good Shepherd, who, leaving the ninety and nine sheep on the mountains, went to seek one which had gone astray, on whose weakness He had such compassion that He vouchsafed to lay it on His own sacred shoulders and so bring it back to the flock (Luke 15:4–5).

CHAPTER XXVIII. Of those who, being often corrected, do not amend

5 Mar. 5 July. 4 Nov.

If any brother who has been frequently corrected for some fault, or even excommunicated, do not amend let a more severe chastisement be applied: that is, let the punishment of stripes be administered to him. But if even then he do not correct himself, or perchance (which God forbid), puffed up with pride, even wish to defend his deeds: then let the Abbot act like a wise physician. If he hath applied fomentations and the unction of his admonitions, the medicine of the Holy Scriptures, and the last remedy of excommunication or corporal chastisement, and if he see that his labours are of no avail, let him add what is still more powerful – his own prayers and those of all the brethren for him, that God, Who is all-powerful, may work the cure of the sick brother. But if he be not healed even by this means, then at length let the Abbot use the sword of separation, as the Apostle saith: “Put away the evil one from you” (1 Corinthians 5:13). And again: “If the faithless one depart, let him depart” (1 Corinthians 7:3), lest one diseased sheep should taint the whole flock.

The Abbot is bound to use the greatest care, and to strive with all possible prudence and zeal, not to lose any one of the sheep committed to him. The loss of a sheep is no trifling matter. The current prices for sheep in Ireland are between €5.25 and €5.40 a kilogram; ewes are going for between €2.80 and €3.00 a kilogram. A male sheep weighs between 45 and 160 kilograms; a ewe weighs between 45 and 100 kilograms; an average lamb weighs about 36.5 kilograms. This means that a sheep may sell for up to €540.00, a ewe for up to €300.00, and a lamb for about €192.00 You will understand, I think, why Saint Benedict uses the image of a shepherd taking pains not to lose any one of the sheep committed to him. You will also understand why a shepherd will go after a stray sheep. Monks are worth more than sheep. Speaking not of sheep, but of sparrows, Our Lord asks, “Are not five sparrows sold for two farthings, and not one of them is forgotten before God? Yea, the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not therefore: you are of more value than many sparrows” (Luke 12:6). And you are of more value than many sheep.

Every novice is, in a certain sense, an investment in the future of the monastery. Each professed monk adds value to the monastic family in the sight of angels and men. This is why, just as a sheep farmer is vigilant over his flock, so must the abbot be vigilant over the novices and monks of the community. Unlike the sheep farmer, who may eliminate weak or sickly lifestock and selectively breed the strong and healthy animals, the abbot “must know that he hath undertaken the charge of weakly souls, and not a tyranny over the strong.” The abbot is to fear the threat of the prophet Ezechiel, through whom God said, “What ye saw to be fat that ye took to yourselves, and what was diseased ye cast away” (Ezechiel 34:3–4).

In a Benedictine monastery the weak and diseased are not cast out unless, after having tried every possible remedy, including the powerful intercessory prayer of the whole community united under the abbot, it becomes clear that the sick brother constitutes a danger to the health and well-being of the whole flock. The abbot does not come lightly to such a conclusion. He must show a boundless patience, never despairing of the mercy of God, and relying on the grace of Christ deployed in every manner of weakness. He must imitate the loving example of the Good Shepherd and go tirelessly in search of the stray sheep who may lie injured and bleating in some dark place or deep ravine. The abbot will lavish compassion and care on such a one, even to the point of carrying it back into the safety of the flock on his own shoulders.

What are these two weight-bearing shoulders of the abbot? They are intercessory prayer and sacrifice. The abbot must accustom himself to praying for his ailing sons and to making sacrifices for them, for “there is no way of casting out such spirits as this except by prayer and fasting” (Matthew 17:2). The abbot’s secret prayer for his sons avails them much in the sight of God, for when the abbot prays, he unites himself to the prayer of Christ who is “always living to make intercession for us” (Hebrews 7:25). The abbot does more by interceding for his sons than he does by preaching to them or by instructing them. The adoring silence of the abbot is more profitable to his sons than all his other acts of government.

I am think of Pope Benedict XVI, who renounced the exercise of every duty of the Sovereign Pontiff except that of ceaseless intercession for the whole Church. In effect, by renouncing all the world perceives of the papal office, he has entered more deeply into what the Father alone sees: the essential work of prayer for the Church. What matters for the life of the Church is not what the media report; what matters is what the Father sees done in secret.

But thou when thou shalt pray, enter into thy chamber, and having shut the door, pray to thy Father in secret: and thy Father who seeth in secret will repay thee. (Matthew 6:6)

We cannot forget the words that Pope Benedict XVI spoke on 14 February 2013:

And although I am about to withdraw, I remain close to all of you in prayer, and I am sure that you too will be close to me, even if I am hidden from the world.

The silence and hiddenness of Pope Benedict is, I think, the rock upon which the Church can rest in the midst of tempest. In the solitude of the Monastery Mater Ecclesiae in Rome, an old man keeps watch over the Church, like an abbot making intercession for his monks.

If he see that his labours are of no avail, let him add what is still more powerful – his own prayers and those of all the brethren. (Chapter XXVIII)