Consideretur semper in eis imbecillitas (XXXVII)

CHAPTER XXXVII. Of Old Men and Children

16 Mar. 16 July. 15 Nov.

Although human nature is of itself drawn to feel pity for these two times of life, namely, old age and infancy, yet the authority of the Rule should also provide for them. Let their weakness be always taken into account, and the strictness of the Rule respecting food be by no means kept in their regard; but let a kind consideration be shewn for them, and let them eat before the regular hours.

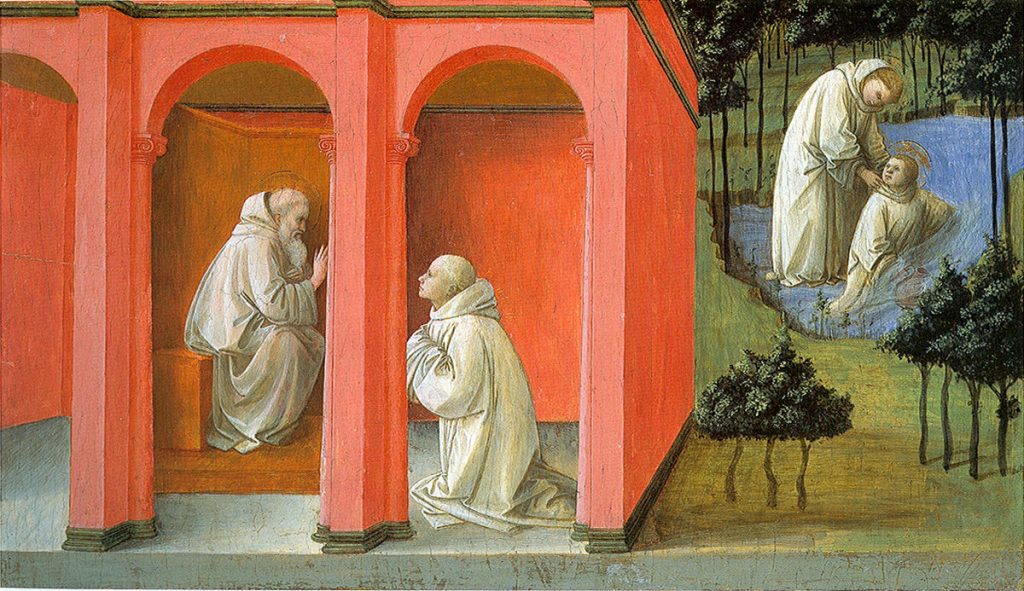

The youngest man here is not quite nineteen and the eldest is sixty–six. In Saint Benedict’s day there would have been children in the monastery: little boys like Saint Placid, entrusted to the monks and offered to God. There would have been youths also, like the adolescent Saint Maurus, the holy Patriarch’s trusted disciple. And there would have been elders, men in their declining years; fifty years would have been considered a good old age.

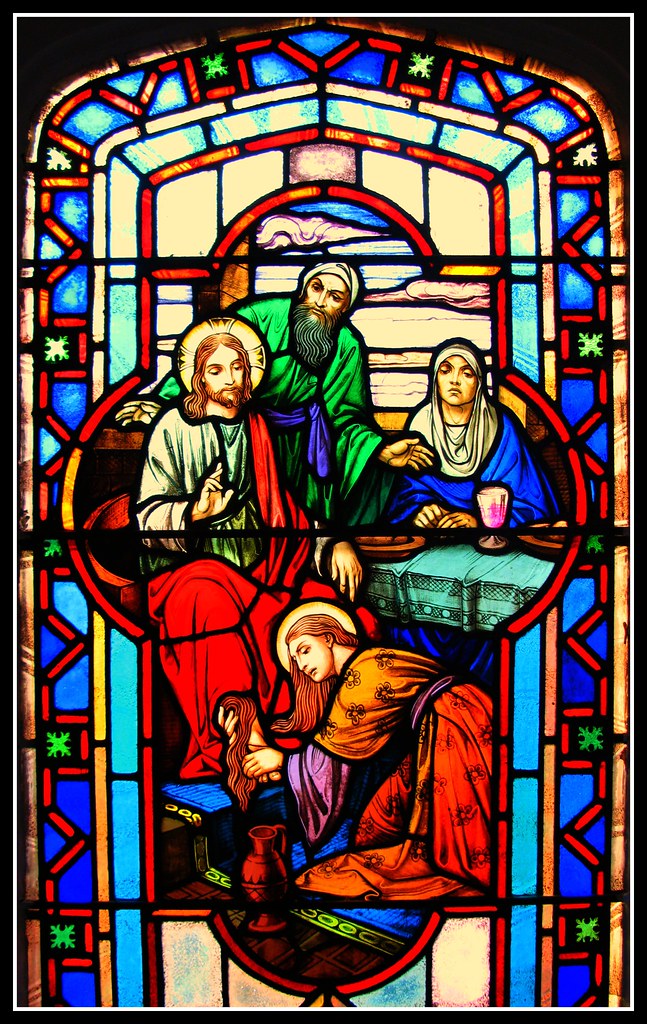

The human heart is naturally moved to pity at the sight of a child’s weakness or an elder’s frailty. Nonetheless, Saint Benedict, knowing the vagaries of human sentiments, provides for children and elders with the authority of the Rule. The first principle Saint Benedict sets forth is this: “Let their weakness be always taken into account”. Consideretur semper in eis imbecillitas. Consideration for weakness runs through the entire Rule; it is, in fact, characteristic of Benedictine life. In our day, when legalised abortion and euthanasia threaten human life both at the beginning and the end of its course, the dignity that Saint Benedict confers on children and old men is particularly significant. As the Psalm says, “Let the old with the younger, praise the name of the Lord”. Senes cum junioribus, laudent nomen Domini (Psalm 148:12).

Although the military motif is present in the Holy Rule, notably in the Prologue, where Saint Benedict speaks of “taking up the strong and bright weapons of obedience, in order to fight for the Lord Christ, our true king”, the paradigm of Benedictine life is the family, not the militia. In a military body all are expected to march to the same pace; one who is unfit for the goal is eliminated. All is in function of the operation. In the Benedictine monastery, there are allowances for weaknesses. The man who cannot keep up the pace is not excluded. He is treated with pia consideratio, kind and devoted consideration.

Nothing is more contrary to the mind of Saint Benedict than the attempt to impose a uniform standard of observance on all. Each age and each state of health has strengths and weaknesses. Saint Dorotheos of Gaza said: “In the mercy of God, the little thing done with humility will enable us to be found in the same place as the saints who have labored much and been true servants of God.” The brother unable to fast may have a gift for comforting the afflicted. The brother unable to rise early may have a gift of perseverance in prayer, even on his bed. The brother strong in ascetical exploits may be weak in other areas that, at the end of the day, are far more important than being able to deny oneself food, drink, and sleep. Saint Benedict operates out of the Apostle’s comprehensive vision of the Body of Christ:

Now there are diversities of graces, but the same Spirit; And there are diversities of ministries, but the same Lord; And there are diversities of operations, but the same God, who worketh all in all. And the manifestation of the Spirit is given to every man unto profit. To one indeed, by the Spirit, is given the word of wisdom: and to another, the word of knowledge, according to the same Spirit; To another, faith in the same Spirit; to another, the grace of healing in one Spirit: To another, the working of miracles; to another, prophecy; to another, the discerning of spirits; to another, diverse kinds of tongues; to another, interpretation of speeches. But all these things one and the same Spirit worketh, dividing to every one according as he will. For as the body is one, and hath many members; and all the members of the body, whereas they are many, yet are one body, so also is Christ. (1 Corinthians 12:4–12)

Saint Benedict sets forth a second principle in this chapter: “Let a kind consideration (pia consideratio) be shewn for them”. There is not a monastery, nor a parish, nor a family in which these two principles of compassion will not find concrete applications, for the Church, in all her various configurations, includes the little, the frail, and the poor.The pia consideratio and the infirmitatum consideratio of the Holy Rule do not, however exclude a certain rigor when the abbot judges that a brother will be strengthened by asking more of him rather than less. Saint Benedict says in the Prologue:

But if anything be somewhat strictly laid down, according to the dictates of sound reason, for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not therefore fly in dismay from the way of salvation, whose beginning cannot but be strait and difficult.

And in Chapter LVIII, with regard to the duties of the Father Master in schooling a novice, he says:

Let all the hard and rugged paths by which we walk towards God be set before him.

Nothing is more difficult for an abbot than knowing when to apply the principles of pia consideratio and of infirmitatum consideratio and when to direct a brother into paths that are hard and rugged, strait and difficult. For my part, if I must err, I prefer to err on the side of pia consideratio and of infirmitatum consideratio. Saint Isaac the Syrian puts it this way:

Ever let mercy outweigh all else in you. Let our compassion be a mirror where we may see in ourselves that likeness and that true image which belong to the Divine nature and Divine essence. A heart hard and unmerciful will never be pure.