Deus, in adjutorium meum intende (XVII)

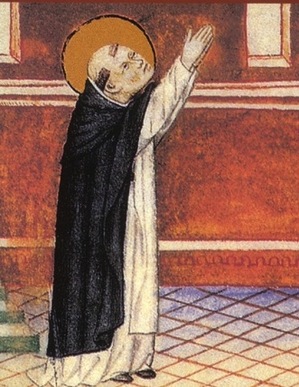

I find this image of Saint Dominic at prayer so expressive of the Deus in adjutorium that I had to use it, even though it does not depict Saint Dominic in the act of choral prayer, but rather in secret prayer. Nonetheless it shows clearly that Saint Dominic’s intimate personal prayer was shaped by the liturgy, and that the embodiment of prayer in gestures accompanied him from the choir to his cell.

I find this image of Saint Dominic at prayer so expressive of the Deus in adjutorium that I had to use it, even though it does not depict Saint Dominic in the act of choral prayer, but rather in secret prayer. Nonetheless it shows clearly that Saint Dominic’s intimate personal prayer was shaped by the liturgy, and that the embodiment of prayer in gestures accompanied him from the choir to his cell.

CHAPTER XVII. How Many Psalms Are to Be Sung at These Hours

20 Feb. 21 June. 21 Oct.

We have now disposed the order of the psalmody for the Night-Office and for Lauds: let us proceed to arrange for the remaining Hours. At Prime, let three Psalms be said separately and not under one Gloria. The hymn at this Hour is to follow the verse, Deus in adjutorium, before the Psalms be begun. Then at the end of the three Psalms, let one lesson be said, with a versicle, the Kyrie eleison, and the Collect.* Tierce, Sext and None are to be recited in the same way, that is, the verse, the hymn proper to each Hour, three Psalms, the lesson and versicle, Kyrie eleison, with the Collect. If the community be large, let the Psalms be sung with antiphons: but if small, let them be sung straight forward.* Let the Vesper Office consist of four Psalms with antiphons: after the Psalms a lesson is to be recited; then a responsory, a hymn and versicle, the canticle from the Gospel, the Litany and Lord’s Prayer, and finally the Collect. Let Compline consist of the recitation of three Psalms to be said straight on without antiphons; then the hymn for that Hour, one lesson, the versicle, Kyrie eleison, the blessing and the Collect.

Where Prayer Begins

Saint Benedict orders that the Hours are to begin with the first verse of Psalm 69: Deus, in adjutorium meum intende; Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina. One cannot begin to pray without a special grace of God; “No man can say the Lord Jesus, but by the Holy Ghost” (1 Corinthians 12:3). Prayer begins not in the human heart, but in the Heart of God; it is a divine initiative. When a monk, or a whole monastic choir, send heavenward the immense cry, Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina, one hears in it the urgent plea of every human heart for communion with God, the thirst of millions of souls for living water.

The Grace of the Holy Ghost

I have long had an inner awareness that the Deus in adjutorium calls down the grace of the Holy Ghost in a unique way. Does not the Apostle say that, “the Spirit also helpeth our infirmity. For we know not what we should pray for as we ought; but the Spirit himself asketh for us with unspeakable groanings. And he that searcheth the hearts, knoweth what the Spirit desireth; because he asketh for the saints according to God” (Romans 8:26-27)?

Beginning Well

The recollected quality or spiritual tenor of an Office is directly proportionate to the attention and devotion brought to bear upon the Deus in adjutorium. An Office well begun will unfold peacefully and in a gentle attention to the presence of God. An Office begun badly, that is to say, in a distracted manner, without having prepared one’s choir books before hand, or in the rush of a last-minute arrival in one’s choir stall, will be troubled from start to finish. This, at least, is my experience. It is always good to arrive in one’s choir stall (or at statio outside of choir) several minutes before the Office is to begin. One’s choir books should be prepared and marked in advance. One needs to take the time to breathe before attempting to chant an Office.

Embodied Prayer

The gestures that accompany the Deus in adjutorium are as important as the words. Sacred gestures are the embodiment of prayer: hands folded, with the right thumb crossed over the left, and held with the thumbs at the level of the tip of one’s nose, pointing heavenward like an arrow. Then follows a grand, majestic sign of the cross, made slowly and with gravity. At the doxology, all turn in choir and bow profoundly in adoration of the Most Holy Trinity, rising for the sicut erat in principio.

Listening to Abbot Isaac in Cassian’s Conferences

Saint Benedict’s frequent use of the Deus in adjutorium reflects the ancient monastic practice related by Cassian in Conference X, Chapter 10:

“O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

This verse . . . embraces all the feelings which can be implanted in human nature, and can be fitly and satisfactorily adapted to every condition, and all assaults. Since it contains an invocation of God against every danger, it contains humble and pious confession, it contains the watchfulness of anxiety and continual fear, it contains the thought of one’s own weakness, confidence in the answer, and the assurance of a present and ever ready help. For one who is constantly calling on his protector, is certain that He is always at hand. It contains the glow of love and charity, it contains a view of the plots, and a dread of the enemies, from which one, who sees himself day and night hemmed in by them, confesses that he cannot be set free without the aid of his defender.

This verse is an impregnable wall for all who are labouring under the attacks of demons, as well as impenetrable coat of mail and a strong shield. It does not suffer those who are in a state of moroseness and anxiety of mind, or depressed by sadness or all kinds of thoughts to despair of saving remedies, as it shows that He, who is invoked, is ever looking on at our struggles and is not far from His suppliants. It warns us whose lot is spiritual success and delight of heart that we ought not to be at all elated or puffed up by our happy condition, which it assures us cannot last without God as our protector, while it implores Him not only always but even speedily to help us.

This verse, I say, will be found helpful and useful to every one of us in whatever condition we may be. For one who always and in all matters wants to be helped, shows that he needs the assistance of God not only in sorrowful or hard matters but also equally in prosperous and happy ones, that he may be delivered from the one and also made to continue in the other, as he knows that in both of them human weakness is unable to endure without His assistance. I am affected by the passion of gluttony. I ask for food of which the desert knows nothing, and in the squalid desert there are wafted to me odours of royal dainties and I find that even against my will I am drawn to long for them. I must at once say: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

I am incited to anticipate the hour fixed for supper, or I am trying with great sorrow of heart to keep to the limits of the right and regular meagre fare. I must cry out with groans: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” Weakness of the stomach hinders me when wanting severer fasts, on account of the assaults of the flesh, or dryness of the belly and constipation frightens me. In order that effect may be given to my wishes, or else that the fire of carnal lust may be quenched without the remedy of a stricter fast, I must pray: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” When I come to supper, at the bidding of the proper hour I loathe taking food and am prevented from eating anything to satisfy the requirements of nature: I must cry with a sigh: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

When I want for the sake of steadfastness of heart to apply myself to reading a headache interferes and stops me, and at the third hour sleep glues my head to the sacred page, and I am forced either to overstep or to anticipate the time assigned to rest; and finally an overpowering desire to sleep forces me to cut short the canonical rule for service in the Psalms: in the same way I must cry out: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” Sleep is withdrawn from my eyes, and for many nights I find myself wearied out with sleeplessness caused by the devil, and all repose and rest by night is kept away from my eyelids; I must sigh and pray: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

While I am still in the midst of a struggle with sin suddenly an irritation of the flesh affects me and tries by a pleasant sensation to draw me to consent while in my sleep. In order that a raging fire from without may not burn up the fragrant blossoms of chastity, I must cry out: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” I feel that the incentive to lust is removed, and that the heat of passion has died away in my members: In order that this good condition acquired, or rather that this grace of God may continue still longer or forever with me, I must earnestly say: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

I am disturbed by the pangs of anger, covetousness, gloominess, and driven to disturb the peaceful state in which I was, and which was dear to me: In order that I may not be carried away by raging passion into the bitterness of gall, I must cry out with deep groans: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” I am tried by being puffed up by accidie, vainglory, and pride, and my mind with subtle thoughts flatters itself somewhat on account of the coldness and carelessness of others: In order that this dangerous suggestion of the enemy may not get the mastery over me, I must pray with all contrition of heart: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

I have gained the grace of humility and simplicity, and by continually mortifying my spirit have got rid of the swellings of pride: in order that the “foot of pride” may not again “come against me,” and “the hand of the sinner disturb me,” and that I may not be more seriously damaged by elation at my success, I must cry with all my might, “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” I am on fire with innumerable and various wanderings of soul and shiftiness of heart, and cannot collect my scattered thoughts, nor can I even pour forth my prayer without interruption and images of vain figures, and the recollection of conversations and actions, and I feel myself tied down by such dryness and barrenness that I feel I cannot give birth to any offspring in the shape of spiritual ideas: In order that it may be vouchsafed to me to be set free from this wretched state of mind, from which I cannot extricate myself by any number of sighs and groans, I must full surely cry out: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

Again, I feel that by the visitation of the Holy Spirit I have gained purpose of soul, steadfastness of thought, keenness of heart, together with an ineffable joy and transport of mind, and in the exuberance of spiritual feelings I have perceived by a sudden illumination from the Lord an abounding revelation of most holy ideas which were formerly altogether hidden from me: In order that it may be vouchsafed to me to linger for a longer time in them I must often and anxiously exclaim: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

Encompassed by nightly horrors of devils I am agitated, and am disturbed by the appearances of unclean spirits, my very hope of life and salvation is withdrawn by the horror of fear. Flying to the safe refuge of this verse, I will cry out with all my might: “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.”

Again, when I have been restored by the Lord’s consolation, and, cheered by His coming, feel myself encompassed as if by countless thousands of angels, so that all of a sudden I can venture to seek the conflict and provoke a battle with those whom a while ago I dreaded worse than death, and whose touch or even approach I felt with a shudder both of mind and body: In order that the vigour of this courage may, by God’s grace, continue in me still longer, I must cry out with all my powers “O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me.” We must then ceaselessly and continuously pour forth the prayer of this verse, in adversity that we may be delivered, in prosperity that we may be preserved and not puffed up.

Let the thought of this verse, I tell you, be turned over in your breast without ceasing. Whatever work you are doing, or office you are holding, or journey you are going, do not cease to chant this. When you are going to bed, or eating, and in the last necessities of nature, think on this. This thought in your heart may be to you a saving formula, and not only keep you unharmed by all attacks of devils, but also purify you from all faults and earthly stains, and lead you to that invisible and celestial contemplation, and carry you on to that ineffable glow of prayer, of which so few have any experience. Let sleep come upon you still considering this verse, till having been moulded by the constant use of it, you grow accustomed to repeat it even in your sleep. When you wake let it be the first thing to come into your mind, let it anticipate all your waking thoughts, let it when you rise from your bed send you down on your knees, and thence send you forth to all your work and business, and let it follow you about all day long.

This you should think about, according to the Lawgiver’s charge, “at home and walking forth on a journey,” sleeping and waking. This you should write on the threshold and door of your mouth, this you should place on the walls of your house and in the recesses of your heart so that when you fall on your knees in prayer this may be your chant as you kneel, and when you rise up from it to go forth to all the necessary business of life it may be your constant prayer as you stand.