Dominici schola servitii (Prologue 7)

7 Jan. 8 May. 7 Sept.

We have, therefore, to establish a school of the Lord’s service, in the setting forth of which we hope to order nothing that is harsh or rigorous. But if anything be somewhat strictly laid down, according to the dictates of sound reason, for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not therefore fly in dismay from the way of salvation, whose beginning cannot but be strait and difficult. But as we go forward in our life and in faith, we shall with hearts enlarged and unspeakable sweetness of love run in the way of God’s commandments; so that never departing from His guidance, but persevering in His teaching in the monastery until death, we may by patience share in the sufferings of Christ, that we may deserve to be partakers of His kingdom. Amen.

Saint Benedict announces his purpose clearly: “We have, therefore, to establish a school of the Lord’s service”. The Rule of the Master cites the words by which Jesus invites us to become His disciples—discite a me— and to place ourselves at His school:

Take up my yoke upon you, and learn of me, because I am meek, and humble of heart: and you shall find rest to your souls. For my yoke is sweet and my burden light. (Matthew 11:29–30)

Saint Benedict, in his own way, alludes to the same words of Jesus, by saying that, in the institution of the school of the Lord’s service, he hopes “to order nothing that is harsh or rigorous”. Moderation and humanity have always characterised Benedictine life; harshness and rigorism are foreign to its ethos. In this, I think, the gentle and courteous Saint Francis de Sales, took a page from our father Saint Benedict. The passage from the Epistle to Titus, that is read at the Mass of Dawn at Christmas, corresponds to Saint Benedict’s ordering of “nothing that is harsh or rigorous”.

Cum autem benignitas et humanitas apparuit Salvatoris nostri Dei.

But when the benignity and humanity of God our Saviour appeared. (Titus 3:4)

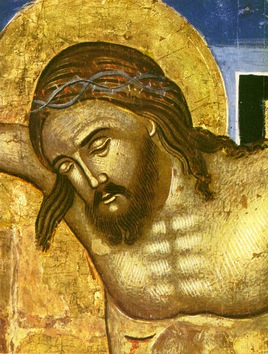

Jesus, meek and humble of heart, is the revelation of the benignity and humanity of God. If anything marks the Rule of Saint Benedict from beginning to end, it is the benignitas et humanitas that are the fruit of a long contemplation of the Face of Christ, and of His Heart, in the Gospels and in the Sacrament of His Love. God is, at certain hours and seasons, severe, but He is never harsh. God, at certain hours and seasons, exacts much —and even everything—of those whom He loves, but without rigorism.

But if anything be somewhat strictly laid down, according to the dictates of sound reason, for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not therefore fly in dismay from the way of salvation whose beginning cannot but be strait and difficult.

The demands of the monastic observance are always tempered by sound reason; they are ordered to the amendment of vices, that is to say, of deeply–rooted sinful habits of thinking, and speaking, and doing, and to the preservation of charity, which is the life of God in us. If a man find the monastic observance costly and difficult, it is because the “good days” promised him as a workman of the Lord require that he lose everything and die to himself and to his most cherished personal ideas and theories about many things, beginning with the monastic life itself, and holiness, and prayer, and mortification.

The foolish according to the world come to the monastery to become wise, and the wise according to the world come to the monastery to become foolish. There comes a point in the first months or years in the cloister when, having read all the right books about what monastic life ought to be, none of it seems to make sense. A novice is normally reduced, in one way or another, to the pathetic state of Jeremias, who, having been called by the Lord said: “Ah, ah, ah, Lord God: behold, I cannot speak, for I am a child” (Jeremias 1:6). This is why we so often read together the admonition from the second chapter of Sirach:

Son, when thou comest to the service of God, stand in justice and in fear, and prepare thy soul for temptation. Humble thy heart, and endure: incline thy ear, and receive the words of understanding: and make not haste in the time of clouds. Wait on God with patience: join thyself to God, and endure, that thy life may be increased in the latter end. Take all that shall be brought upon thee: and in thy sorrow endure, and in thy humiliation keep patience. For gold and silver are tried in the fire, but acceptable men in the furnace of humiliation. (Sirach 2:1–5)

The school of the Lord is the circle of those who, gathered around Him, learn His teaching in order to put it into practice. These Our Lord calls His mother and brethren: “My mother and my brethren are they who hear the word of God, and do it” (Luke 8:21). Saint Benedict’s monastery is, at once, a school and a family, and both are constituted by obedience. Our father, Saint Antony of Egypt, is the great model of obedience to the Word of God. Saint Athanasius, in the Life of Antony, relates that no sooner had the young Antony heard the words of the Lord in the Gospel, “If you would be perfect, go and sell what you have and give to the poor; and come follow Me and you shall have treasure in heaven” (Matthew 19:21), than he went out immediately to put into practice what he had heard.

Saint Benedict speaks of the school of the Lord, the dominici schola servitii. The word servitium has a rich connotation. Like the Hebrew word abodah, the Latin servitium can mean servitude or enslavement; it can also designate liturgical worship. The sacred cultus, the liturgical worship of God in choir and at the altar, is the service of the Lord. It is in this sense that the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council used the word in defining monastic life: “The principal duty of monks is to offer a service to the divine majesty at once humble and noble within the walls of the monastery” (Perfectae Caritatis, art. 9). The Benedictine monastery is a dominici schola servitii insofar as it is a school of prayer and, most notably, of liturgical prayer.

At the end of the Prologue, Saint Benedict points to a luminous horizon. He speaks of “going forward in our life and in faith”, that is, of growing old in the monastery and of walking, more and more, “by faith, and not by sight” (2 Corinthians 5:7). He speaks of the dilation of the heart: a Benedictine monk, characteristically, loses all that is narrow, small, mean, measured, and confining, and enters into “the love of Christ in all its breadth and length and height and depth” (Ephesians 3:18). Saint Benedict speaks of the “unspeakable sweetness” of the love of Christ. A thirteenth century English Cistercian poet would express this very thing:

Quam bonus te quaerentibus!

sed quid invenientibus?

Nec lingua valet dicere,

nec littera exprimere:

expertus potest credere,

quid sit Jesum diligere.

How good Thou art to those who seek!

But what to those who find? Ah! this

Nor tongue nor pen can show

The love of Jesus, what it is,

None but His loved ones know.

A man enters the monastery to “run in the way of God’s commandments, never departing from His guidance, but persevering in His teaching in the monastery until death”. The prophecy of Isaias becomes a personal realisation and a daily experience:

This Lord of ours, who fashioned the remotest bounds of earth, is God eternally; he does not weaken or grow weary; he is wise beyond all our thinking. Rather, it is he who gives the weary fresh spirit, who fosters strength and vigour where strength and vigour is none. Youth itself may weaken, the warrior faint and flag, but those who trust in the Lord will renew their strength, like eagles new-fledged; hasten, and never grow weary of hastening, march on, and never weaken on the march. (Isaias 40:28–31)

Perseverance in the monastery until death is a daunting proposition, no less than perseverance in holy marriage until death. The man who invests his life in nothing, the man who does not risk all for all, the man who never pledges himself to another, lives on the surface of things, and will die having missed the opportunity to give his Yes unreservedly to God.

What is this passing life if not a one–time opportunity to say “Yes” unreservedly to God? The Yes of one’s life—it is the Fiat of the Virgin, and the Pater, in manus tuas of Jesus on the Cross, and the Suscipe me of Saint Benedict—is the one thing that fulfils a man’s purpose and corresponds to God’s perfect design. Such a Yes—Fiat; Pater, in manus tuas; Suscipe me—is, of necessity, costly. It is a participation in the sufferings of Christ, a willingness to be marked with His wounds, and remain on His Cross, and enter with him into the silence of His tomb and of His tabernacles. Consent to this and He will make your wounds flower; He will make of the Cross a marriage bed; He will intone in you a new song out of the very silence of death: the paschal Alleluia, that, as Aemiliana Löhr says, “slowly rises above the grave with the blood of Christ on its wings”.