Et ex caritate, confidens de adiutorio Dei, oboediat (LXVIII)

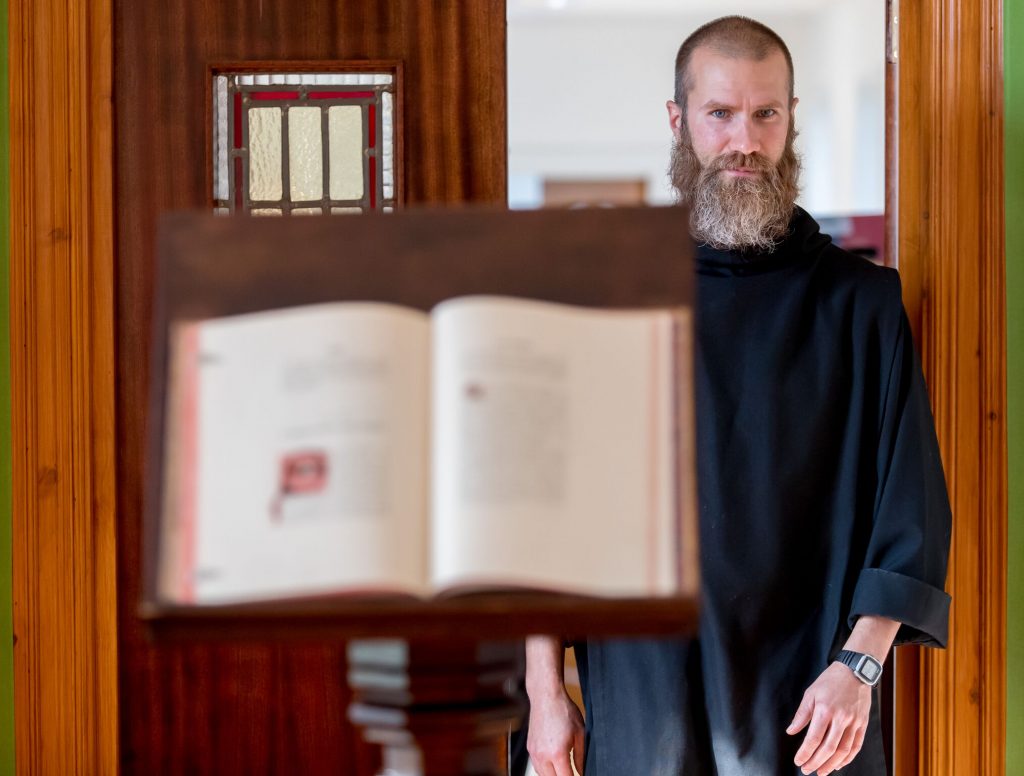

CHAPTER LXVIII. If a Brother be commanded to do Impossibilities

26 Apr. 26 Aug. 26 Dec.

If on any brother there be laid commands that are hard and impossible, let him receive the orders of him who biddeth him with all mildness and obedience. But if he seeth the weight of the burden altogether to exceed his strength, let him seasonably and with patience lay before his Superior the reasons of his incapacity to obey, with out shewing pride, resistance, or contradiction. If, however, after this the Superior still persist in his command, let the younger know that it is expedient for him; and let him obey for the love of God, trusting in His assistance.

Why would an abbot lay upon a brother commands that are hard and impossible? Saint Benedict is speaking here from the perspective of the brother, not from that of the abbot. Saint Benedict knows well that at certain hours and seasons life, a brother may find some things hard and impossible. The brother may be weary, or beset with temptations, or feeling unwell. He may be afraid of risking something new and different. He may feel that a particular task is above him . . . or beneath him. He may think another better suited to the task. All the same, Saint Benedict says, “let him receive the orders of him who biddeth him with all mildness and obedience”. Cum omni mansuetudine et oboedientia. A brother receives an order with mildness when he offers no resistance.

There are brothers who, even before an order is given, have thought up ten reasons why what is asked ought to be done differently, or not done at all, or be delayed, or reconsidered. Such brothers are always ready with a contrary argument. Their psychological default is set in resistance mode. Such brothers lack the virtue of mildness, also called meekness. Saint Thomas says that meekness is the virtue that tempers or mitigates anger.

Meekness disposes man to the knowledge of God, by removing an obstacle; and this in two ways. First, because it makes man self-possessed by mitigating his anger, as stated above; secondly, because it pertains to meekness that a man does not contradict the words of truth, which many do through being disturbed by anger. (II, 2. Question 157, art. 4)

It sometimes happens that a brother is in the grip of a repressed anger. This anger may the spawn of a festering resentment. It may have nothing at all to do with the matter at hand. It surely derives from pride, but pride is a many–headed monster. Anger, especially when it is a slow–cooking anger, seething below the surface, impairs a man’s reason and clouds his vision. The abbot, because he represents authority, easily becomes the object of a brother’s unresolved conflicts and rage. A brother must first recognise the anger that is eating him up. If he repents of it, confesses it, and asks Our Lord to destroy the very roots of it in him, he will become capable of responding meekly to what is asked of him.

Meekness, as virtues go, does not get very good press. The world sees meekness as weakness. There was a cartoon character at the beginning of the last century named Caspar Milquetoast. He was described by his creator, H.T. Webster, as “the man who speaks softly and gets hit with a big stick”. The term “milquetoast” (referring to a bland and inoffensive food for nervous or sensitive stomachs) came into popular parlance to mean weak, shrinking, ineffectual, hyper–sensitive, fearful, and timid. This is not the virtue of meekness. The meek man harnesses the passion that drives anger and uses it, instead, to face difficulties with equanimity, to replace traits of bitterness and harshness with sweetness of demeanour and gentleness. Father Garrigou–Lagrange says:

Meekness is that which is most visible and most agreeable in the practice of charity; it is what constitutes its charm. It appears in the gaze, the smile, the bearing, the speech; it doubles the value of a service rendered. And besides, it protects the fruits of charity and zeal; it makes counsels and even reproaches acceptable. In vain will we have zeal for our neighbor, if we are not meek; we appear not to love him and we lose the benefit of our good intentions, for we seem to speak through passion rather than reason and wisdom, and consequently we accomplish nothing.

Meekness is particularly meritorious when practiced toward those who make us suffer; then it can only be supernatural, without any admixture of vain sensibility. It comes from God and sometimes has a profound effect on our neighbor who is irritated against us for no good reason. Let us remember that the prayer of St. Stephen called down grace on the soul of Paul, who was holding the garments of those who stoned the first martyr. Meekness disarms the violent. (The Three Ages of the Interior Life, Part Three)

Meekness is, for Saint Benedict, a monk’s first response when something, anything, especially things that appear hard and impossible are asked of him. Such a meekness is the fruit of humility. It makes life in the monastery more pleasant, more peaceful, and more joyful. In such an atmosphere, a brother can more easily find the courage to set about doing things that at first appear daunting or unreasonable. “Jesus, meek and humble of heart, make our hearts like unto Thine”.

To meekness, Saint Benedict adds obedience. The meek monk has an affable, gracious way about him that indicates a ready good will to do or, at least, to try to do whatever will be asked of him. A superior should never have to take one look at a monk and conclude, “I cannot ask anything of this brother. His mind and heart are closed before I even open my mouth”. A superior ought never be afraid of asking something of a brother. Happy the abbot who is able to say, “I can ask anything of any one of my monks. I know that, no matter what, I will meet with the fundamental attitude of obedience that, at least, makes a man say, ‘Reverend Father, I am certainly willing to try'”. The meek monk is open and approachable; the obedient monk is willing to take the first step.

It may happen that, even with good will and effort, a monk sees that the weight of the burden altogether exceeds his strength. This becomes an occasion to practice humility and simplicity. Saint Benedict says, “let him seasonably and with patience lay before his Superior the reasons of his incapacity to obey”. Seasonably, opportune, means at the right moment. The right moment is not, for example, immediately before the Divine Office or Holy Mass, nor is it at the hour of lectio divina, nor after Compline. Again, if a brother perceives that the abbot, or any other superior, is preoccupied, harried, or pulled in several other directions, it is best for that brother to keep his representations for a more opportune moment. Patienter. The brother is to state his case patiently. One cannot expect the abbot to grasp immediately all the contingencies and circumstances of every difficulty. Much is gained by speaking amiably and calmly. The abbot must be patient with his monks, but the monks must also be patient with their abbot. Having listened to his son, the abbot will say, “You were open to what I asked of you. You didn’t refuse. Thank you for helping me to see that this thing exceeds your strength. I shall look for another solution. Be at peace”.

Saint Benedict indicates three attitudes that are always reprehensible: non superbiendo aut resistendo vel contradicendo, pride, resistance, and contradiction. The prideful brother is convinced that he knows better, that he knows more, that he alone sees rightly.What is stopped up by pride is opened by humility. Saint Thomas says that humility is “a disposition that facilitates the soul’s untrammeled access to spiritual and divine goods” (II:2, Question 161, article 5). The humble brother, even if he be less gifted naturally, can, effectively, do more than the prideful brother, because the humble brother has free access to spiritual and divine goods, while the prideful brother is “sent empty away” (Luke 1:53).

The resistant brother gives the impression of pushing away whatever comes from outside himself; he is interiorly murmuring “no” at every turn. The contradicting brother has a particular affection for the conjunction “but” as in “Yes, but”, “No, but”, “Not now, but”.

The last sentence of Chapter LXVIII is, in some way, a distillation of Saint Benedict’s doctrine: “If, however, after this the Superior still persist in his command, let the younger know that it is expedient for him; and let him obey for the love of God, trusting in His assistance”. Saint Benedict already said in the Prologue: “If anything be somewhat strictly laid down, according to the dictates of sound reason, for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not therefore fly in dismay from the way of salvation, whose beginning cannot but be strait and difficult”. Here, he adds, et ex caritate, confidens de adiutorio Dei, oboediat. “Let him obey for the love of God”. Nothing opens a soul to grace like the little prayer, “For love of Thee, O Jesus”.

Already in Chapter V, our holy father said, “Obedience without delay becometh those who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ”. The monk who obeys ex caritate, out of love, will do astonishing things, like Saint Maurus running over the waters to rescue the boy Placid. He will discover that even the smallest thing done in response to an actual grace, out of love for Christ, opens him to receive other graces. And, in this way, he begins to “go forward with a dilated heart and to run in the way of God’s commandments with the unspeakable sweetness of love” (Prologue).

The phrase, confidens de adiutorio Dei, sums up the reliance on divine grace that runs through the Holy Rule from beginning to end. Saint Benedict fosters in his monks an attitude of complete confidence in God, and of utter reliance on divine grace. Omnia possum in eo qui me confortat (Philippians 4:13). Saint Benedict is never far from Saint Paul who says, “I can do all things in him who strengtheneth me”, or as it is given in Monsignor Knox’s translation, “Nothing is beyond my powers, thanks to the strength God gives me”. Chapter LXVIII ends with the word oboediat. Let him obey. Nothing is ever lost by obedience when the act of obedience is driven by love and sustained by divine grace.