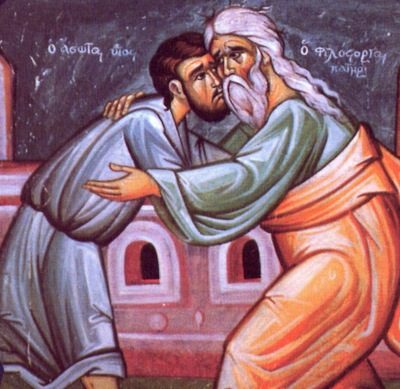

The cure of the sick brother (XXVIII)

CHAPTER XXVIII. Of Those Who, Being Often Corrected, Do Not Amend

5 Mar. 5 July. 4 Nov.

If any brother who has been frequently corrected for some fault, or even excommunicated, do not amend let a more severe chastisement be applied: that is, let the punishment of stripes be administered to him. But if even then he do not correct himself, or perchance (which God forbid), puffed up with pride, even wish to defend his deeds: then let the Abbot act like a wise physician. If he hath applied fomentations and the unction of his admonitions, the medicine of the Holy Scriptures, and the last remedy of excommunication or corporal chastisement, and if he see that his labours are of no avail, let him add what is still more powerful – his own prayers and those of all the brethren for him, that God, Who is all-powerful, may work the cure of the sick brother. But if he be not healed even by this means, then at length let the Abbot use the sword of separation, as the Apostle saith: “Put away the evil one from you.” And again: “If the faithless one depart, let him depart,” lest one diseased sheep should taint the whole flock.

It is clear from the tone of this chapter that our father Saint Benedict had a firsthand experience of the things he describes. There have always been Christians, even within the cloister, who resist the grace of conversion. One can easily develop an affection for one’s sin. One convinces oneself that a particular indulgence makes life with all its hardships less unbearable. One talks oneself into believing that one cannot change when, in truth, one no longer wants to change. How easy it is to grow old in one’s sins the way one grows used to wearing a comfortable pair of slippers. There are two verses in Psalm 108 that describe what happens when sin becomes habitual:

And he put on cursing, like a garment: and it went in like water into his entrails, and like oil in his bones. May it be unto him like a garment which covereth him; and like a girdle with which he is girded continually. (Psalm 108:18–19)

God forbid that, in the monastic life, patterns of sin should become so routine as to blind a monk to the point of not seeing that his habitual offenses are alienating him from God and will precipitate his descent into hell. The offender, deluded by pride, can even begin to rationalise his attachment to sin. The Abbot, therefore, is obliged to intervene before occasional faults metastasize into the systemic faults (vices) that are much more difficult to excise from one’s life, and from the life of the community. Saint Benedict orders the interventions of the Abbot in five incremental steps. These five steps are:

1) Fomentations and Admonitions. These are remedies that any wise physician would employ. A fomentation (or poultice) is the application of a hot compress, with or without some medicinal herb, to relieve pain and reduce inflammation. It is not uncommon that certain vices are merely an attempt to treat an underlying emotional pain. Repeated sin causes spiritual inflammation. What sort of fomentations would the abbot use? Kind words capable of opening the heart, words of light and of hope, strong words to quicken the will and spur it in the right direction. Very often a few honest, heart-to-heart conversations are sufficient to bring about an opening to grace and a fresh beginning. The abbot will, without fail, invite the afflicted brother to have humble recourse to the Mother of God. Of all the admonitions an abbot can make, this is the most effective. As soon as the Blessed Virgin Mary enters a man’s life, she begins to set it in order. Her very presence purifies the atmosphere, and moves the heart to conversion.

2) The medicine of the Holy Scriptures. The Word of God is a powerful cleansing agent, a mighty disinfectant, a healing balm. The Abbot will direct the wayward brother to certain passages of Sacred Scripture—especially to those given in the Holy Mass and the Divine Office— enjoining him to read them, to repeat them, to pray them until, at length, they effect an inward conversion. Certain patterns of sin can be traced back to the neglect and, then, abandonment of lectio divina. A good point of departure is Evagrius’ little handbook for spiritual combat, Antirrhetikos. Each of you received a copy of this book last Christmas. The Rosary is the simplest way of applying the medicine of the Holy Scriptures to the soul. Each of the mysteries of the Rosary is a “word” in the biblical sense (dabar, logos, verbum), that is, an acting word that places the soul in contact with the divine virtus.

Et omnis turba quærebat eum tangere: quia virtus de illo exibat, et sanabat omnes.

And all the multitude sought to touch him, for virtue went out from him, and healed all. (Luke 6:19)

3) Excommunication. By excommunication a brother is excluded from the choir and from the common table. He is given time out, time to think, time to be alone with himself. Excommunication is an opportunity to enter into the desert. “Therefore, behold I will allure her, and will lead her into the wilderness: and I will speak to her heart” (Osee 2:14). Time apart can be a salutary thing. Time apart can also present real dangers, especially for brothers who are already given to self–isolation. The very thing that may help one brother may prove to be the downfall of another. Life in Saint Benedict’s day and culture was intensely corporate and social. Excommunication was a salutary shock. Today men, accustomed to working in front of a computer screen in a cubicle, are inured to isolation. Even the traditional family meal is disappearing in the West. Horrible expressions such as “grabbing a bite” suggest that a dehumanising isolation has penetrated even into the sanctuary of home life. In some homes the television set has been given the place of honour at table. The Eucharistic biblical image given by the psalmist has, in many places, become remote and unfamiliar.

For thou shalt eat the labours of thy hands: blessed art thou, and it shall be well with thee.

Thy wife as a fruitful vine, on the sides of thy house. Thy children as olive plants, round about thy table.

Behold, thus shall the man be blessed that feareth the Lord. (Psalm 127:2–4)

4) Corporal Punishment. Saint Benedict does not shrink from the use of corporal punishment; he knows that man is a composite of body and soul. One will remember that “caning” was practiced in many schools right up into the 1960s and, in some places, even later. While there is no question of reviving such practices today, the underlying principle is that the physical may be engaged in the process of conversion, so as to dispose one hardened in sin to yield to the gentle and powerful action of divine grace. While beatings are no longer administered to this end, some form of corporal participation in the labour of conversion remains salutary. This may be as simple as depriving a brother of his portion of wine (a classic remedy, especially in Italy), or of sending him to clean out the chicken coop, or to clear away brush, or to weed an overgrown patch of garden.

5) The Prayer of the Abbot and of All the Brethren. It may surprise some to find that Saint Benedict puts this remedy last. He is referring here, not merely to a private supplication on behalf of the erring brother, but to a full-scale mobilisation of the entire community’s intercessory prayer that God, Who is all-powerful, may work the cure of the sick brother. In Saint Benedict’s day this may very well have taken on a public quasi-liturgical character. Today, an Abbot may direct his community to join him in making a novena for a brother in dire spiritual straits, or he may gather his community around him in a confident prayer of intercession, trusting in Our Lord’s words: “Again I say to you, that if two of you shall consent upon earth, concerning any thing whatsoever they shall ask, it shall be done to them by my Father who is in heaven. For where there are two or three gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:19-20). In my own experience, nothing is as effective as the Rosary; there is no problem or difficulty that cannot be solved or resolved by faithful persevering recourse to the Rosary.

Separation

When all of these remedies have been brought to bear upon a sick brother, the Abbot may be obliged to act in the best interest of the monastic family, by using the sword, or scalpel, of separation. It is clear that, for Saint Benedict, this is a last resort. The monk hardened in sin remains a son of the monastic household; it is a wrenching and terrible thing to have to send him away, analogous to sending away one’s own troubled adolescent in order to protect the younger siblings of the family. In our day, an Abbot cannot proceed with separation from the community without following strictly the procedure required by Canon Law.