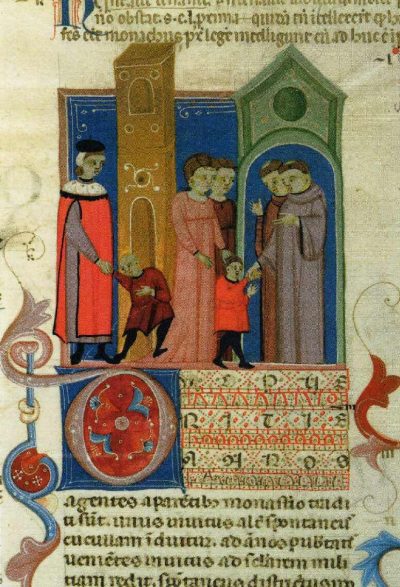

How the younger boys are to be corrected (XXX)

CHAPTER XXX. How the younger boys are to be corrected

7 Mar. 7 July. 6 Nov.

Every age and understanding should have its proper measure of discipline. As often, therefore, as boys or others under age, or unable to understand the greatness of the penalty of excommunication, commit faults, let them be punished by severe fasting or sharp stripes, in order that they may be cured.

It is easy to treat this chapter of the Holy Rule as obsolete. We do not, after all, have pueri oblati in the cloister and have no intention of reviving the ancient practice. Every monastery, however, counts among its members men who, in one way or another, have not yet altogether emerged from a certain immaturity. There will always be brothers marked by childhood traumas. There will always be brothers who struggle with arrested emotional development, or with affective deprivation in childhood, or with the sequels of a dysfunctional family life. Allow me to present some examples:

•Brother Macarius’ parents divorced when he was seven. He watched the drama unfold, not quite understanding what was happening, feeling torn apart and utterly helpless. Brother Macarius, thirty years later, still feels torn apart and cannot put down roots in one place. When he is here, he wants to be there. And when he is there, he wants to be here. Nowhere is really home. The grown–up Brother Macarius is restless, unstable, and yet adaptable to a variety of situations. He has tried his hand at many things, yet stayed with none of them. Brother Macarius needs stability, wise mentoring, and faithful enduring friendship.

•Brother Winnoc was sent off to a Catholic boarding school at the age of twelve. Although he was very brave about it, he wasn’t emotionally ready to leave his home and family. Unconsciously, he decided to remain twelve years old even while going on to excel in many things. There is a part of Brother Winnoc that is still afraid to navigate the uncharted and troubled waters of adolescence and young adulthood. The grown–up Brother Winnoc is loyal, reliable, and well–organised. At the same time, he falls prey to anxiety and morbid introspection. Brother Winnoc needs someone to whom he can confide his secret fears and the thoughts that trouble him.

•Brother Philoxenus suffered violent aggression of a sexual nature at the age of five. The episode was shrouded in secrecy, but left left him with a terror of being found out. Little Philoxenus felt dirty and ashamed. The violent aggression so affected him that even forty years later, there is a part of him that is still five years old, waiting to be freed from the effects of what he suffered and angry that it was allowed to happen. Brother Philoxenus tried, from an early age, to mask the effects of what he suffered by creating an image of himself that would win him approval and conceal his shameful secret. There is, nonetheless, deep inside him the damaged five year old boy who still waits for Mummy and Daddy to set things right and protect him. The grown–up Brother Philoxenus is sensitive to criticism, but also reflective and enterprising. Brother Philoxenus needs much reassurance and affirmation.

•Brother Savio fell ill with rheumatic fever when he was seven years old. His mother and father, both of whom had to work to support the family, were beside themselves with worry. Little Savio was bundled up and put in the care of his grandmother and two maiden aunts. For almost a year, they didn’t allow his feet to touch the ground. They carried him everywhere and allowed him no physical activity. He was not permitted to go to school or to receive his First Holy Communion with the other children of his class. The television became his world. A kind tutor came to teach him at home three days a week. Savio grew into a frail adolescent. He was often short of breath and, consequently, unable to participate in sports or group activities. Savio became a fine pianist and, later, an organist. The grown–up Brother Savio dispenses himself easily from community activities. He secretly misses the nurturing intimacy of his grandmother and aunts. There is still a part of him that is ill at ease with his male peers, even after years in the monastery. Brother Savio needs to be held to the common timetable and be encouraged to participate fully in community life.

•Brother Bruno’s Dad was a heavy drinker. He was absent from the home for long stretches of time and, even when he was physically present, he wasn’t emotionally available to his son. Little Bruno learned to manage things on his own and felt better when he was in control. He still needs to control himself, others, and his environment. He often feels that things are spinning out of his control and this makes him feel anguish and anger. If, for some reason, the abbot disappoints him, he relives the pain of every disappointment with his father. The grown–up Brother Bruno is meticulous, well–organised, and critical of those who fail to meet his standards. He can flare up in anger when disappointed. Brother Bruno needs to let go of the need to control everyone and everything and accept that others will not always meet his standards.

•Brother Kyle’s Dad was a good provider, but his work was the most important thing in his life. He gave Kyle and his siblings the little time that remained, but even then he was focused more on work than on engaging with his wife and children. He left the care of the children to Nancy, Kyle’s Mom. Nancy, for her part, grew resentful of being left alone to look after the children, discipline them, and reward them. She loved the children, but also resented them for consuming every waking moment of her life. Feeling abandoned by her husband, Nancy came to demand from her children the attention she craved from her husband. Kyle felt overwhelmed and confused by the demands being placed on him. Even before the age of puberty, Kyle learned to withdrew into his own inner world whenever he felt afraid, or threatened, or confused. No one at home seemed to notice or to care. Brother Kyle still withdraws when he feels overwhelmed, afraid, threatened, or confused. The grown–up Brother Kyle is hyper–sensitive to criticism and easily feels threatened. He is lacking in personal discipline. Brother Kyle needs more personal attention than others; he also needs to be held accountable for the use of his time.

Brothers Macarius, Winnoc, Philoxenus, Savio, Bruno, and Kyle represent the boys likely to be found in any monastery. Any one of us can, I think, identify with Brothers Macarius, Winnoc, Philoxenus, Savio, Bruno, and Kyle. How are we to treat the boys in the monastery? We have to win their confidence, challenge them, and impose limits on them, knowing that, as Saint Benedict says, “Every age and understanding should have its proper measure of discipline.”

Should Brothers Macarius, Winnoc, Philoxenus, Savio, Bruno, and Kyle not have been admitted to the monastery. Should they have been sent away before profession? Should a monastery receive men who do not correspond to the normative vocational profile? What about men challenged by an arrested development? If we were to exclude all such individuals from the monastery, we would, first of all, find ourselves without some very gifted and capable men. We would also become poorer in men of great insight, empathy, and compassion. Grace repairs and perfects nature, but it does this over time and, yes, even over a lifetime. Believe in grace, then, and be patient.

There is no doubt that the abbot and master of novices must exercise prudence in the assessment of candidates. Certain pathologies are incompatible with the monastic life. At the same time, one must not demand such a perfection of candidates, that virtually everyone marked by the bruises, fractures, deficits, and wounds of life in a sinful world is excluded.

I was given a sting to distress my outward nature, an angel of Satan sent to rebuff me. Three times it made me entreat the Lord to rid me of it; but he told me, My grace is enough for thee; my strength finds its full scope in thy weakness. More than ever, then, I delight to boast of the weaknesses that humiliate me, so that the strength of Christ may enshrine itself in me. I am well content with these humiliations of mine, with the insults, the hardships, the persecutions, the times of difficulty I undergo for Christ; when I am weakest, then I am strongest of all. (2 Corinthians 12:7–10)

A psychologist sympathetic to the monastic vocation can help a brother identify the knot that holds him bound; he can even begin to loosen the knot. Cognitive distortions can be pinpointed and one can effectively change one’s thinking. There is a point, however, at which one has to admit that there are knots that even a hundred years of therapy cannot untie completely. There is a point at which one has to admit that there are in some men affective deficits for which no amount of human affirmation can compensate. There are cases of arrested development that no treatment method can remedy. The abbot who fathers his sons in Christ, will always refer them to Him and to the power of His grace. Can grace build on a misshapen and faulty natural foundation? Yes, grace, working through the sacraments, in prayer, and by compassionate human instruments, can, over time, effectively fill the cracks and fissures of the most broken human foundation. Even the boys of the monastery can become great grown–up saints.