(VII: The Ninth Degree)

6 Feb. 7 June. 7 Oct.

The ninth degree of humility is, that a monk refrain his tongue from speaking, keeping silence until a question be asked him, as the Scripture sheweth: “In much talking thou shalt not avoid sin”: and, “The talkative man shall not be directed upon the earth.”

All the Fathers teach that talkativeness is a sure sign of a diseased heart and a restless spirit. Likewise, all the Fathers recommend holding one’s tongue lest, in giving way to much talk, one fall into sins of pride, vainglory, exaggeration, mendacity, rash judgment, impurity, vulgarity, backbiting, and deprecation. So much of life in the world consists in talking. In the electronic age, the vice of talkativeness, while not altogether silencing the wagging tongue, makes use of fingers flying across the keyboard. How many sins are committed by way of the electronic media: instant messaging, Twitter, Facebook, text messaging, and so many other means of which I have not heard! How many friendships are poisoned, how many reputations damaged, how many families divided, how many lies propagated in this way! At no time in one’s life ought one desist from praying: “Set a watch, O Lord, before my mouth: and a door round about my lips.” (Psalm 140:3). For Saint John Climacus,

Talkativeness is the throne of vainglory on which it loves to show itself and make a display. Talkativeness is a sign of ignorance, a door to slander, a guide to jesting, a servant of falsehood, the ruin of compunction, a creator of despondency, a precursor of sleep, the dissipation of recollection, the abolition of watchfulness, the cooling of ardour, the darkening of prayer.

Saint John Climacus goes on to say that,

Deliberate silence is the mother of prayer, a recall from captivity, preservation of fire, a supervisor of thoughts, a watch against enemies, a prison of mourning, a friend of tears, effective remembrance of death, a depicter of punishment, a meddler with judgment, an aid to anguish, an enemy of freedom of speech, a companion of quiet, an opponent of desire to teach, increase of knowledge, a creator of contemplation, unseen progress, secret ascent.

And the Saint concludes:

He who has become aware of his sins has controlled his tongue, but a talkative person has not yet got to know himself as he should. The friend of silence draws near to God, and by secretly conversing with Him, is enlightened by God. The silence of Jesus put Pilate to shame, and by a man’s stillness vainglory is vanquished. (Saint John Climacus, The 11th Step, On Silence and Talkativeness)

Five hundred years after Saint John Climacus, Saint Bernard, who knew well how to use wit and sarcasm in order deliver a point, presents a portrait of the talkative monk:

When vanity increases, and the bladder begins to be inflated, it becomes necessary to loosen the belt and allow a larger outlet for the air, otherwise the bladder will burst. So the monk who is unable to discharge his superabundant store of unseemly merriment by laughter or by gesture, breaks forth with the words of Elihu, “My belly is as new wine which wanteth vent, which bursteth the new vessels” (Job 22:19). He must speak out or break down. “For he is full of matter to speak of, and the spirit of his bowels constraineth him” (Job 22:18).

He hungers and thirsts for hearers, at whom he may throw his banalities, to whom he may pour out his feelings, and let them know what a fine fellow he is. But when he has found his opportunity of speaking — if the conversation turns on literary matters — old and new points are brought forward; he airs his ideas in loud and lofty tone. He interrupts his questioner and answers before he is asked. He himself puts the question and gives the answer, nor does he even allow the person to whom he is talking to finish his remarks.

When the striking of the silence gong puts a stop to conversation, he complains that a full hour is not a sufficient allowance, and asks for indulgence that he may go on with his gossip after the time for it is over — not to add to the knowledge of any one else, but to boast of his own. He has the power but not the purpose of giving useful information. His care is not to teach you or to learn from you things which he does not know, but that the extent of his learning may be made known. If the subject under discussion is religion, he is forward with his vision and his dreams. He upholds fasting, prescribes vigils, and maintains the paramount importance of prayer. He enlarges at great length but with excessive conceit on patience, humility and all the virtues in turn, with the intention that you on hearing him should say, “Out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh” (Matthew 12:34) and that, “a good man out of his good treasure bringing forth good things” (Matthew 12:35).

If the talk turns on light subjects he becomes more loquacious, because he is on more familiar ground. If you hear the torrent of his conceit you may say that his mouth is a fount of such buffoonery as to move even strict and sober monks to light laughter. To put it shortly, mark his swagger in his chatter. (Saint Bernard, The Twelve Degrees of Humility and Pride, Chapter XIII)

The author of the Imitation of Christ teaches nothing different, but he expresses it differently, and with a persuasiveness that never fails to touch the heart:

If you withdraw yourself from unnecessary talking and idle running about, from listening to gossip and rumors, you will find enough time that is suitable for holy meditation.

Very many great saints avoided the company of men wherever possible and chose to serve God in retirement. “As often as I have been among men,” said one writer, “I have returned less a man.” We often find this to be true when we take part in long conversations. It is easier to be silent altogether than not to speak too much. To stay at home is easier than to be sufficiently on guard while away. Anyone, then, who aims to live the inner and spiritual life must go apart, with Jesus, from the crowd.

No man appears in safety before the public eye unless he first relishes obscurity. No man is safe in speaking unless he loves to be silent. No man rules safely unless he is willing to be ruled. No man commands safely unless he has learned well how to obey. No man rejoices safely unless he has within him the testimony of a good conscience. (The Imitation of Christ, Chapter XX)

Concretely, what means can a monk take to mortify talkativeness and become a lover of silence. I shall propose three means:

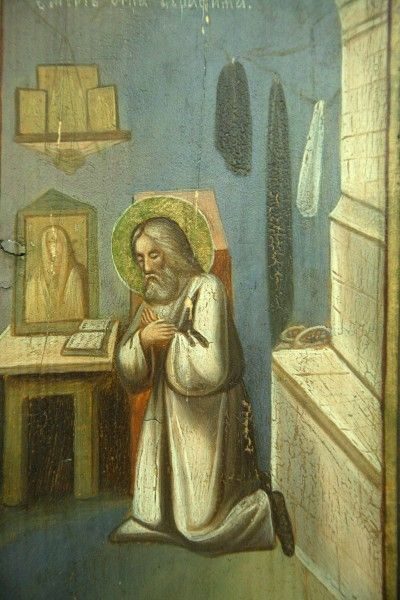

- The first means is to frequent the company of the Blessed Virgin Mary — even more, to live habitually in her presence — by invoking her sweet name, by going before her images, and especially by praying the Rosary. There is a beautiful icon of Saint Seraphim of Sarov that depicts the holy elder kneeling, with his hands crossed on his breast, before an icon of the Mother of God holding her hands in the same position. The icon teaches a profound truth: the Mother of God imparts something of the silence and humility of her Immaculate Heart to those who persevere in calling upon her. The love of silence is one of the signs of a true devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Every man needs to pour out his heart to one who listens with attention, sympathy, and compassion. Learn to pour out your heart to the Immaculate Virgin Mary. Every time you pray to the Mother of God, you will come away with a quieted heart, and loving silence more.

- The second means is to practice lectio divina assiduously. Lectio divina is the ladder of monks; the summit of the ladder opens onto the silence of God. Love the Word of God. Read the Word of God in order to hear it. Listen to it in order to repeat it and learn it by heart. Repeat it in order to make it your prayer. Make it your prayer in order to become wholly docile to the operations of the Holy Ghost, and through His operations, united to the Father through the Son. Thus will you pass, adoring, into the silence of the Holy Trinity.

- The third means is to go before the Sacred Host and to enter, by adoration, into the silence of the Host. Once a man has experienced the silence of the Host, he will want to return to it again and again. He will want to hold it in his heart and flee from anything that would sully it, profane it, or diminish it. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament is the great school of monastic silence. You will learn more from abiding in the silence of the Host than from sitting at the feet of the world’s greatest theologians. There you will learn the meaning of Our Lord’s words: “Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:42).

Wisdom, Let us attend!