Pervenies (LXXIII)

CHAPTER LXXIII. That the whole observance of Perfection is not set down in this Rule

1 May. 31 Aug. 31 Dec.

We have written this Rule, in order that, by observing it in Monasteries, we may shew ourselves to have some degree of goodness of life, and a beginning of holiness. But for him who would hasten to the perfection of religion, there are the teachings of the holy Fathers, the following whereof bringeth a man to the height of perfection. For what page or what word is there in the divinely inspired books of the Old and New Testaments, that is not a most unerring rule for human life? Or what book of the holy Catholic Fathers doth not loudly proclaim how we may by a straight course reach our Creator? Moreover, the Conferences of the Fathers, their Institutes and their Lives, and the Rule of our holy Father Basil – what are these but the instruments whereby well-living and obedient monks attain to virtue? But to us, who are slothful and negligent and of evil lives, they are cause for shame and confusion. Whoever, therefore, thou art that hasteneth to thy heavenly country, fulfil by the help of Christ this least of Rules which we have written for beginners; and then at length thou shalt arrive, under God’s protection, at the lofty summits of doctrine and virtue of which we have spoken above.

And so, once again, we come to the last chapter of the Holy Rule. In some way, I think, alongside of the liturgical cycles of feasts and seasons, our life is measured by the reading of the Holy Rule three times yearly.

All things have their season, and in their times all things pass under heaven. A time to be born and a time to die. A time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted. (Ecclesiastes 3:1–2)

How many times will a monk have heard the reading of the Holy Rule over a lifetime? Saint Benedict tells us why we read and re–read the Rule, and why, spontaneously, we make it our first reference: “In order that, by observing it in monasteries, we may shew ourselves to have some degree of goodness of life, and a beginning of holiness”. Saint Benedict speaks here with the profound modesty and discretion that characterise him: “some degree of goodness of life, and a beginning of holiness”. Here there is no feverish exaggeration, no inflated idealism, no spectacular feats of ascetism; there is rather the humble and patient realism of the Gospel:

So is the kingdom of God, as if a man should cast seed into the earth, And should sleep, and rise, night and day, and the seed should spring, and grow up whilst he knoweth not. For the earth of itself bringeth forth fruit, first the blade, then the ear, afterwards the full corn in the ear. (Mark 4:26–28)

Saint Benedict would have us complete the reading of the Holy Rule with an assiduous recourse to Sacred Scripture and to his own “holy Catholic” fathers in God: Cassian, Saint Basil, and the other monastic fathers. We fulfil this injunction of Saint Benedict by a faithful application to lectio divina, and by going frequently to Saint John Cassian and to the Desert Fathers.

Saint Benedict seems, at first glance, to take a rather dim view of our monastic struggle such as it is: “To us”, he says, “who are slothful and negligent and of evil lives”, the writings of the Fathers “are cause for shame and confusion”. Immediately upon saying this, however, he corrects it, lest we be “overwhelmed by excess of sorrow” (Chapter XXVII), or utterly “despair of the mercy of God” (Chapter IV). To the very end of the Rule, Saint Benedict shows himself consistent with his own teaching in Chapter XXVII:

The Abbot is bound to use the greatest care, and to strive with all possible prudence and zeal, not to lose any one of the sheep committed to him. He must know that he hath undertaken the charge of weakly souls, and not a tyranny over the strong.

And so, calling his Holy Rule “the least of Rules”, and addressing us as little ones, as “beginners”, he adds:

Whoever, therefore, thou art that hasteneth to thy heavenly country, fulfil by the help of Christ this least of Rules which we have written for beginners; and then at length thou shalt arrive, under God’s protection, at the lofty summits of doctrine and virtue of which we have spoken above. (Rule Chapter, LXXIII)

The three key phrases in this passage are, without any doubt: adiuvante Christo, “by the help of Christ”; Deo protegente, “under God’s protection”; and pervenies, “thou shalt arrive”. Christ Jesus, the Son of the Virgin, is ever present to those whom Saint Benedict calls “beginners”. Like Saint Peter, walking on the waves, the monk keeps eyes fixed on the face of Jesus, confident in His help and in the protection of God.

But seeing the wind strong, he was afraid: and when he began to sink, he cried out, saying: Lord, save me. And immediately Jesus stretching forth his hand took hold of him, and said to him: O thou of little faith, why didst thou doubt? (Matthew 13:30–31)

At every stage of the monastic journey, the monk needs to receive from the mouth of Christ the words given through the prophet Isaias:

Thou art my servant, I have chosen thee, and have not cast thee away. Fear not, for I am with thee: turn not aside, for I am thy God: I have strengthened thee, and have helped thee, and the right hand of my just one hath upheld thee. Behold all that fight against thee shall be confounded and ashamed, they shall be as nothing, and the men shall perish that strive against thee. Thou shalt seek them, and shalt not find the men that resist thee: they shall be as nothing: and as a thing consumed the men that war against thee. For I am the Lord thy God, who take thee by the hand, and say to thee: Fear not, I have helped thee. (Isaias 41:9–10)

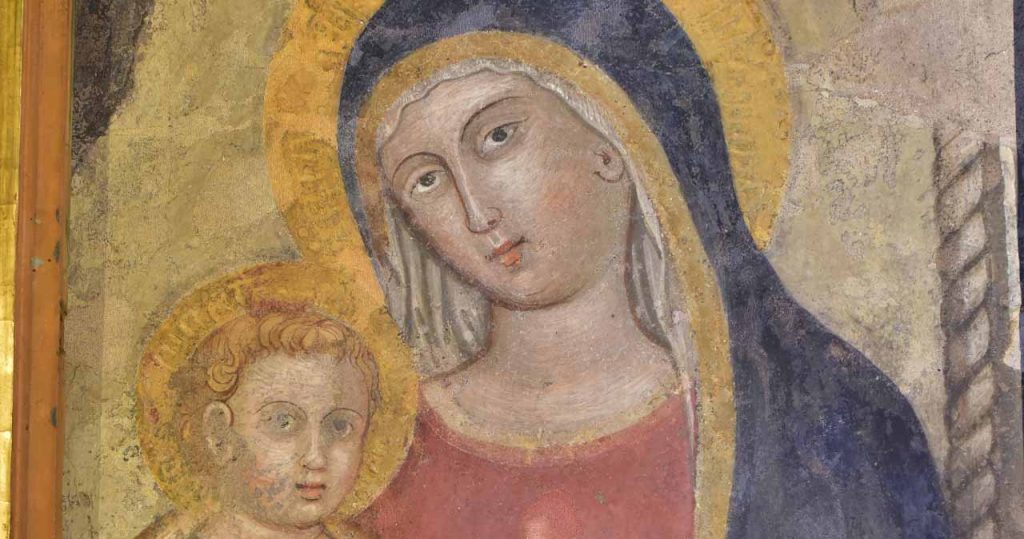

The phrases adjuvante Christo and Deo protegente imply that the Mother of God is also present in the life of a monk, for where Christ gives help, there too is His Virgin Mother. Where God gives protection, there too is the Mediatrix of All Graces, attentive to the needs and struggles of all who, in the midst of strong winds and tempestuous waves, give their faith to her Son. Not for nothing does Saint Bernard, surely one of the greatest abbots of history, say:

O Thou, whosoever thou art, that knowest thyself to be not so much walking upon firm ground, as battered to and fro by the gales and storms of this life’s ocean, if thou wouldest not be overwhelmed by the tempest, keep thine eyes fixed upon this star’s clear shining. If the hurricanes of temptation rise against thee, or thou art headed for the rocks of trouble, look to the star, call upon Mary. If the waves of sin toss thee, look to the star, call upon Mary. If the billows of anger or avarice, or the enticements of the flesh beat against the ship of thy soul, look to Mary. In danger, in difficulty, or in doubt, think on Mary, call upon Mary. (Saint Bernard, Super missus est 2, 17; PL 183, 70-71)

She who, at the wedding feast of Cana said, “They have no wine” (John 2:3), withdrew, after the Ascension of her Son, into the cloister of the Cenacle where, together with the Apostles, she persevered in prayer, holding fast to her Son’s parting words: “And I send the promise of my Father upon you: but stay you in the city till you be endued with power from on high” (Luke 24:49). There, in the Cenacle, on the fiftieth day, the wine for which Our Lady asked at Cana, the Holy Ghost, was given in such superabundance that those who saw and heard them said, “These men are full of new wine” (Acts 2:13).

We conclude our reading of the Holy Rule on the first day of May, the month that Catholic piety dedicates to the Blessed Virgin Mary, recalling the joy that was hers at the Resurrection of her Son; the hope that filled her maternal Heart at His Ascension; the incandescent prayer that was hers in the Cenacle; and the hidden life that was hers in the care of Saint John, who, as he himself says, accepit eam in sua, “took her into all that was his own” (John 19:25). It is not too soon to entrust to the Mother of God the fresh, new reading of the Holy Rule that we shall begin tomorrow. The monk who gives to Mary all his beginnings will not be deprived of her consoling presence in the end. Listen closely, Our Lady, our heavenly abbatissa, repeats to each one of us: pervenies mecum, “with me, thou shalt arrive”.