Omnia dura et aspera per quae itur ad Deum (LVIII:1)

CHAPTER LVIII. Of the Discipline of receiving Brethren into Religion

Continued from 11 Apr.

Let a senior, one who is skilled in gaining souls, be appointed over him to watch him with the utmost care, and to see whether he is truly seeking God, and is fervent in the Work of God, in obedience and in humiliations. Let all the hard and rugged paths by which we walk towards God be set before him.

Saint Benedict would have the Master of Novices forewarn his novice that the monastic journey to God will take him along hard and rugged paths. Praedicentur ei omnia dura et aspera per quae itur ad Deum. The monastic life is not a spiritual pleasure cruise. Omnia dura et aspera. According to Lewis and Short, dura refers to things that are hard, severe, toilsome, troublesome, burdensome, disagreeable, and adverse. Asper, acccording to some authors, derives from the Greek ἀσπαίρω, which means to struggle in agony against death. Others make asper derive from the Latin ab spe, which is the opposite of prosper (pro spe). The idea would be of something hardly bearable or desperate.

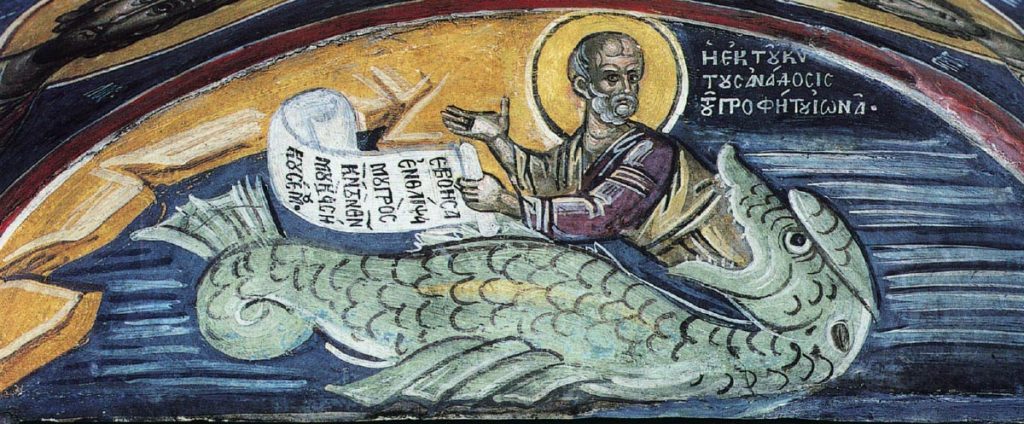

The Father charged with the care of the novices will warn them from the very beginning that they will encounter things that are hard, toilsome, burdensome, and harsh; things that will make them struggle almost to the point of despair. The Canticle of Jonas expresses well the prayer of the monk who is in his cloister as Jonas was in the belly of the fish:

And Jonas prayed to the Lord his God out of the belly of the fish. And he said: I cried out of my affliction to the Lord, and he heard me: I cried out of the belly of hell, and thou hast heard my voice. And thou hast cast me forth into the deep in the heart of the sea, and a flood hast compassed me: all thy billows, and thy waves have passed over me. And I said: I am cast away out of the sight of thy eyes: but yet I shall see thy holy temple again. The waters compassed me about even to the soul: the deep hath closed me round about, the sea hath covered my head. I went down to the lowest parts of the mountains: the bars of the earth have shut me up for ever: and thou wilt bring up my life from corruption, O Lord my God. When my soul was in distress within me, I remembered the Lord: that my prayer may come to thee, unto the holy temple. They that are vain observe vanities, forsake their own mercy. But I with the voice of praise will sacrifice to thee: I will pay whatsoever I have vowed for my salvation to the Lord. (Jonas 2:2–10)

Look at the monastic struggle from the perspective of the capital vices:

Pride

The man who enters the monastery bloated with pride will soon find that everything in the monastic life conspires to make him humble, to reveal his shortcomings and his attachments, and to demolish the false image he had of himself.

Greed

The man who enters the monastery in the grip of greed will soon see that he has to let go of the ownership and control, not only of his finances and possessions, but of everything, including his personal preferences and the employment of his time.

Gluttony

The man who enters the monastery ruled by gluttony, even in very subtle ways, will find it difficult not to eat and drink what he wants, prepared in the way he wants, when he wants. He is obliged to come to terms with a certain inner emptiness and so forsake the things by which he sought to fill up the voids in his life.

Lust

The man who enters the monastery thinking that there at least he will be free of the assaults of lust, will soon discover, as did Saint Augustine, that lust winks at him from every chink and crevice, beckoning him to reconsider his renunciation of the delights of intimate companionship and of sexual pleasure.

Sloth

The man who enters the monastery long accustomed to living in sloth will find that everything in the monastic life militates against taking one’s ease in comfort, against lollygagging, against procrastinating, against arranging all things in view of having to make the least possible effort.

Envy

The man who enters the monastery embittered by the vice of envy will discover that living at close quarters with other men exposes him constantly to attacks of envy. He will find himself saddened by the progress, the talents, and the virtues of others, and embittered by his own inability to advance, and by his own lack of the gifts and virtues that he sees in those around him.

Anger

The man who, in the world, came across as pleasant and meek may, in the monastery, may find himself easily provoked to anger, or inwardly seething about injustices real or imagined, or clenching his fists so as not to punch, or pound, or pulverise something or someone.

A man enters the monastery to attend freely to God and the things of God: vacare Deo. This expression does not only mean to make space for God; it also means to empty oneself in order to give all the space within oneself to God. The purification of one’s inner attachments and clearing away of the accumulated rubble of twenty, thirty, or forty years is a hard struggle, hence, Saint Benedict’s dura et aspera. The monastic life is neither a pleasant ramble through spiritual meadows nor an endless holiday. It is an agony, a struggle. But it is the struggle of one who says with the Apostle, “I can do all things in him who strengtheneth me.” (Philippians 4:13).

Saint Anthony’s threefold teaching is, I think, particularly helpful to the brother who is alarmed at the prospect of the dura et aspera that await him along the monastic journey or that he is already, to some extent, experiencing.

Someone asked Abba Anthony, ‘What must one do in order to please God?’ The old man replied, ‘Pay attention to what I tell you: whoever you may be, always have God before your eyes; whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy Scriptures; in whatever place you live, do not easily leave it. Keep these three precepts and you will be saved.’