Of the Abbot’s Table (LVI)

CHAPTER LVI. Of the Abbot’s Table

9 Apr. 9 Aug. 9 Dec.

Let the table of the Abbot be always with the guests and strangers. But as often as there are few guests, it shall be in his power to invite any of the brethren. Let him take care, however, always to leave one or two seniors with the brethren for the sake of discipline.

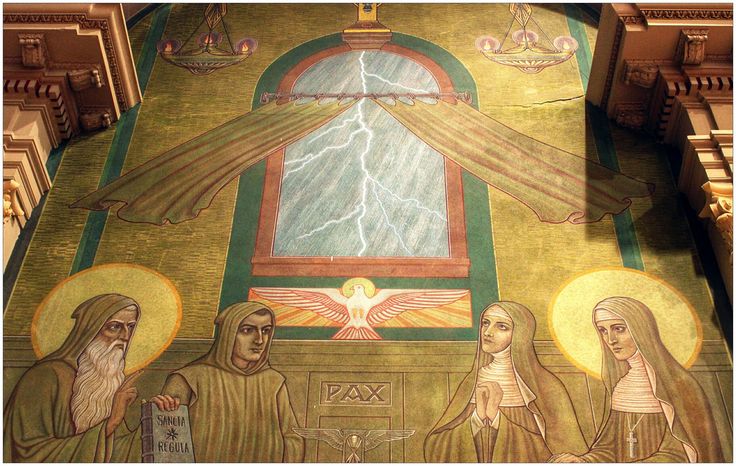

The laws of mediterranean hospitality require that the master of the household eat with his guests. The table is a place of exchange and of communion, of sympathy and of friendship. Ancient monastic stories recount that angels, saints, and even Our Lord Himself sometimes appeared at the door, seeking hospitality.

Behold, I stand at the gate, and knock. If any man shall hear my voice, and open to me the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me. (Apocalypse 3:20)

Our forefathers lived in a atmosphere of faith. There was, even in the humblest realities of life, a compenetration of the supernatural and the natural.

Do not forget to shew hospitality; in doing this, men have before now entertained angels unawares. (Hebrews 13:2)

Saint Benedict foresees that the abbot’s table will be in the guesthouse. It would have been unseemly to impose the fasts and abstinence of the monastic refectory on guests who would have traveled great distances and endured the hardships of the road. One of the Desert Fathers in Egypt surprised his guests by breaking the customary fast and eating with them. When questioned about his apparent lack of rigor, the old father explained that the monastic fast is an evangelical counsel, whereas fraternal charity is a precept of Christ.

Over time, the practice of Benedictine hospitality came to include the reception of male guests at a separate table in the monastic refectory. Given that most guests now come to the monastery for a time of spiritual retreat, this is entirely suitable. The guests thus benefit from the silence of the refectory, from the liturgical prayer before and after the meal, and from the reading. In many monasteries, it is customary for the abbot and a few brethren to join the guests after the meal in the parlour or calefactory (i.e., common room) for a cup of coffee and, on Sundays and feastdays, for dessert. This, too, is entirely suitable, provided that it not be too protracted. Twenty minutes is about right.

Saint Benedict says that as often as there are few guests, it shall be in the abbot’s power to invite any of the brethren to share his table. This is one of the loveliest human touches in the Holy Rule. The father of the monastery can, exceptionally, share a cup of coffee, or even a special meal with two or three of his sons. This gives the abbot an opportunity to exchange freely with the brethren in an atmosphere that is congenial and more relaxed.

Saint Benedict’s abiding concern remains, nonetheless, that the regular observance of the community not be compromised. For this reason, when the abbot is absent from the refectory, one or two seniors remain with the brethren for the sake of good order. Regularity is indispensable to Benedictine life. Saint Benedict knows how to temper the austerity of the regular observance with a pia consideratio for human weakness, “so that no one may be troubled nor grieved in the house of God” (Chapter XXXI)>