What the measure of excommunication should be

CHAPTER XXIV. What the measure of excommunication should be

1 Mar. 1 July. 31 Oct.The measure of excommunication or chastisement should be meted out according to the gravity of the offence, the estimation of which shall be left to the judgment of the Abbot. If any brother be found guilty of lighter faults, let him be excluded from the common table. And this shall be the rule for one so deprived: he shall intone neither Psalm nor antiphon in the Oratory, nor shall he read a lesson, until he have made satisfaction. Let him take his meals alone, after those of the brethren so that if, for example, the brethren eat at the sixth hour, let him eat at the ninth: if they eat at the ninth, let him eat in the evening, until by proper satisfaction he obtain pardon.

For Saint Benedict, to exclude a brother from the common table and silence his voice in choir is to put that brother outside the ebb and flow of daily life in the monastery. In the Mediterranean culture this represents a significant deprivation. Post–modern man suffers from isolation and, yet, at the same time, he chooses isolation over and over again, and even finds the technological means to isolate himself further. Post–modern man, fearful of permanent life–long commitment, drives himself into a state of social isolation and, then, goes to the social media in a desperate attempt to feel connected to someone somewhere, to anyone anywhere, all the while avoiding real engagement and commitment.

One of the most difficult antiphons a Benedictine monk has to learn is the Ecce quam bonum et quam iucundum habitare fratres in unum, “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity” (Psalm 132:1) that we sing at Tuesday Vespers: difficult, I say, not because of the text or melody, but difficult because if a monk is to sing what he lives, and lives what he sings, he must constantly go out of himself toward the other. The man who comes to the monastery intending to live on his own terms will not persevere. The monk, like any other Christian, flourishes only in a context of sacrificial love. There is no getting around the imperative of laying down one’s life for one another: some men do this by martyrdom, others in the context of marriage and family, still others do it in the context of the cœnobium, but no one can follow Christ and escape from it.

I should like to say something about the brother who, for reasons of ill health, is obliged to stay apart from the rhythm and flow of the community life. Such a brother does not choose his isolation; he suffers it. The loneliness imposed by illness can, in effect, delay a brother’s restoration to health. For this reason every brother is bound to reach out to the brother marginalised by illness. The sick or convalescent brother should never be made to feel as if he is excommunicated. On the contrary, he must be surrounded by a most attentive and tender affection, and visited often throughout the day. To visit such a brother is to visit Christ Himself.

An abbot today must exercise the greatest vigilance over the tendency to disengage that increasingly characterises men coming to the cloister. The phenomenon is not a new one. The “rebel without a cause” of the 1950s and the “drop–out” of the 1960s were incipient manifestations of a phenomenon that, with the technological revolution, is acquiring ever–new refinements. Technology, paradoxically feeds off of man’s existential isolation and, at the same time, intensifies that isolation.

One needs to go to Dante’s Inferno in order to see where a society bent on avoiding permanent life–long, exclusive commitments is going. Dante shows us the centre of hell, not as a place of fiery torment, but as a frozen lake, a place of icy cold. The lake of ice is divided into four concentric rounds, each one corresponding to a degree of self–chosen alienation or betrayal: family, community, guests, authority. The souls who find themselves frozen in the Inferno are those who separated themselves from the warmth of human love and, in so doing, separated themselves from the love of God, the source of all love, fornax ardens caritatis (the blazing furnace of charity) and so found themselves frozen in a terrible isolation.

Dante helps us to understand that for Saint Benedict and his monks, community life means salvation. To be separated, even for a time from community life, is strong medicine. In too great a dose it can be deadly. The monk who is cut off, even for a limited time and to a degree, from the life of the community understands that if he persists in his contumacy, or pride, or disobedience, he will find himself frozen in isolation. When a small child is given the punishment of “time out”, it is not long before he begs to be reintegrated into the family circle. To “excommunicate” a child momentarily from the family circle can be salutary; to alienate him for too long from the family circle can harm him irreparably. This is why Saint Benedict would have the measure of excommunication be left to the judgment of the Abbot.

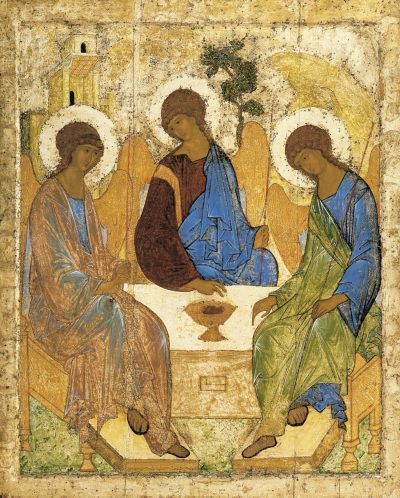

Given post–modern man’s descent into isolation, excommunication may not be a suitable remedy in all cases. The model of our life remains the κοινωνία of the Most Holy Trinity depicted in Roublev’s icon of the Holy Trinity: there we see unity in love expressed in a shared life, in humility, obedience, and mutual reverence. Ubi caritas et amor, Deus ibi est. Where charity and love are, God does there abide.