The sixth degree of humility

3 Feb. 4 June. 4 Oct.

The sixth degree of humility is, for a monk to be contented with the meanest and worst of everything, and in all that is enjoined him to esteem himself a bad and worthless labourer, saying with the prophet: “I have been brought to nothing, and I knew it not: I am become as a beast before Thee, yet I am always with Thee.”

The Sixth Degree of Humility sends us back to the second chapter of Genesis in which the first Adam is presented as God’s labourer: “So the Lord God took the man and put him in his garden of delight, to cultivate and tend it” (Genesis 2:15). The Sixth Degree of Humility sends us, as well, to the work of which Our Lord speaks in His Priestly Prayer:

I have glorified thee on the earth; I have finished the work which thou gavest me to do. And now glorify thou me, O Father, with thyself, with the glory which I had, before the world was, with thee. (John 17:4–5)

And in another place Our Lord speaks of this same work:

My Father worketh until now; and I work. (John 5:17)

It is in this context, and against the background of the parable of the labourers sent into the vineyard (Matthew 20:1–16), that Saint Benedict first introduces the figure of the workman of the Lord in the Prologue of the Holy Rule:

And the Lord, seeking His own workman in the multitude of the people to whom He thus crieth out, saith again: “Who is the man that will have life, and desireth to see good days. And if thou, hearing Him, answer, “I am he,” God saith to thee: “If thou wilt have true and everlasting life, keep thy tongue from evil and thy lips that they speak no guile. Turn from evil, and do good: seek peace and pursue it. And when you have done these things, My eyes will be upon you, and My ears will be open to your prayers; and before you call upon Me, I will say unto you, “Behold, I am here.” What can be sweeter to us, dearest brethren, than this voice of the Lord inviting us? Behold in His loving-kindness the Lord sheweth unto us the way of life.

At every hour of every day, from early morning until the eleventh hour, the Lord Christ, our true King seeks workmen who, together with Him, will consecrate themselves to the Work of God. “Go you also into my vineyard, and I will give you what shall be just” (Matthew 20:4). On the very day of his election, before imparting the Apostolic Blessing urbi et orbi, Pope Benedict XVI described himself as “a simple and humble labourer in the vineyard of the Lord”. Pope Benedict XVI was, I think, drawing upon the imagery of the Prologue and of the Sixth Degree of Humility, which he knows so well. After eight years on the Chair of Peter, Pope Benedict XVI withdrew to a hidden, silent life of prayer, without, however, ceasing to be “a simple and humble labourer in the vineyard of the Lord”. It is by the twelve degrees of humility that a monk enters into the labour of Christ that is the work of redemption. This the labour so poignantly recalled in the Dies Irae:

Quaerens me, sedisti lassus:

redemisti crucem passus:

tantus labor non sit cassus.In weariness You sought for me,

and suffering upon the tree!

let not in vain such labor be.

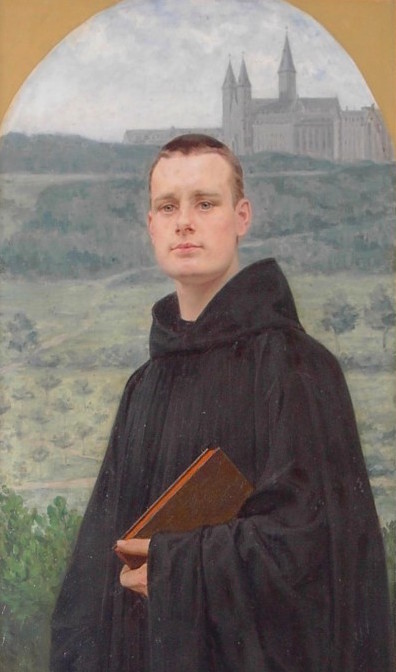

One enters into the tantus labor — so great a labour — of the Redeemer by becoming with Him a victim made over to the Father. This self–offering, by the hands of Christ the Priest and with Christ the Victim, is the essential work of the monk and of any one who enters sacramentally into the mystery of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This was the message of Dom Pius de Hemptinne, the young disciple of Blessed Abbot Marmion. Dom de Hemptinne wrote:

Although Jesus Christ the divine High Priest appeared only once on earth, to offer up His great sacrifice on Calvary; yet, every day He appears in the person of each one of His ministers, to renew His sacrifice on the altar. In every altar, then, Calvary is seen: every altar becomes an august place, the Holy of holies, the source of all holiness. Thither all must go to seek Life, and thither all must continually return, as to the source of God’s mercies. Those who are the Master’s privileged ones, never leave this holy place, but there they “find a dwelling,” near to the altar, so that they never need go far from it; such are monks, whose first care it is to raise temples worthy to contain altars. Making their home by the Sanctuary, they consecrate their life to the divine worship, and every day sees them grouped around the altar for the holy sacrifice. This is the event of the day, the centre to which the Hours, like the centuries, all converge: some as Hours of preparation and awaiting in the recollection of the divine praise — these begin with Lauds and Prime continued by Terce, the third Hour of the day; the others, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline, flow on in the joys of thanksgiving until sunset when the monks chant the closing in of night.

For the son of Saint Benedict, the primary and indispensable way of participating in the Great Work of Christ is by returning to his choir stall seven times daily and once in the night for the Opus Dei. The Divine Office is the ongoing twofold Work of God in Christ; the glorification of God, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and the salvation of men. In an antiphon for the Office of September 14th, the Church sings :

O magnum pietátis opus: mors mortua tunc est, in ligno quando mortua Vita fuit.

O how great a work of love was that when Life and death died together upon the Tree.

The magnum pietátis opus continues, silent and hidden, beneath the humble appearances of the Sacred Host and concealed by the tabernacle. The appearances of the Sacred Host are but a fragile veil beneath which Christ works even now. Souls whom Christ draws into the Holy Sacrifice of the Altar, into the obscurity of the tabernacle, or into the radiance of the monstrance, He yokes to Himself in order that they may labour with Him in the Great Work by which the Father is perfectly glorified and souls are saved. Dom Pius de Hemptinne grasped this when he wrote: “He who knows what the altar is, from it learns to live”.

For the greater number of monks, participation in the labour of Christ may mean engaging in a specific manual or intellectual work undertaken in obedience. Others will labour with Christ by bearing in silence and with good cheer the common burden and heat of the day. Still others will labour with Christ by accepting the very infirmities and limitations that keep them from engaging fully in the normal round of work and prayer. The humiliation of being unable to do all that one would wish to do can be, by God’s design, a singularly effective way of entering into the work of Christ. I think of so many saints, reduced by illness to near inactivity, who entered in the work of Christ by becoming, on the altar of their sickbed, a host with the Host. In the economy of God even infirmity, that by which a man is, as Saint Benedict says, “brought to nothing”, can be a great work of love. It is the last phrase of the Sixth Degree of Humility that gives meaning to all the rest: Et ego semper tecum, “And I am always with thee” (Psalm 72:23).