Patiently with a quiet conscience

1 Feb. 2 June. 2 Oct.

The fourth degree of humility is, that if in this very obedience hard and contrary things, nay even injuries, are done to him, he should embrace them patiently with a quiet conscience, and not grow weary or give in, as the Scripture saith: “He that shall persevere to the end shall be saved” (Mt 24:13). And again: “Let thy heart be comforted, and wait for the Lord” (Ps 26:14) And shewing how the faithful man ought to bear all things, however contrary, for the Lord, it saith in the person of the afflicted: “For Thee we suffer death all the day long; we are esteemed as sheep for the slaughter” (Ps 43:22; Rom 8:36). And secure in their hope of the divine reward, they go on with joy, saying: “But in all these things we overcome, through Him Who hath loved us” (Rom 8:37). And so in another place Scripture saith: “Thou hast proved us, O God; Thou hast tried us as silver is tried by fire; Thou hast led us into the snare, and hast laid tribulation on our backs” (Ps 65:10–11). And in order to shew that we ought to be under a superior, it goes on to say: “Thou hast placed men over our heads” (Ps 65:12). Moreover, fulfilling the precept of the Lord by patience in adversities and injuries, they who are struck on one cheek offer the other: to him who taketh away their coat they leave also their cloak; and being forced to walk one mile, they go two (cf. Mt 5:39–41). With Paul the Apostle, they bear with false brethren, and bless those that curse them (cf. 2 Cor 11:26; 1 Cor 4:12).

The first thing that strikes one upon reading the fourth degree of humility is, once more, Saint Benedict’s dependence on Sacred Scripture. One can find as many as ten references to Sacred Scripture in the fourth degree; here Saint Benedict draws upon the Psalms, Saint Matthew, and Saint Paul. Our holy patriarch, being entirely faithful to all that was essential in the monastic tradition before him, sends us again and again to the Word of God. Saint Benedict is the man of tradition, faithfully passing on what he himself received. Our father Saint Benedict can say with the Apostle: “For I delivered unto you first of all, which I also received” (1 Cor 15:3). The son of Saint Benedict loves the Word of God that resounds in the Church; he immerses himself in the Sacred Scriptures as given him, day after day, in the Divine Office and in Holy Mass.

Saint Benedict speaks to us today, in the Fourth Degree of Humility, of the “hard and contrary things, nay even injuries” that a monk may encounter in the struggle to obey. Saint Benedict will return to this question in Chapter LXVIII, “If a Brother Be Commanded to Do Impossibilities”. That obedience becomes, at least at certain hours, a bitter struggle, is no surprise to anyone who has tried to live as a monk. The first and, I think, the last struggles of a monk will pertain to obedience. Obedience is costly. I have known monks who are learned in all the sacred sciences, punctilious in keeping every rubric, full of zeal for the strictest observance of the Rule and, all the same, lacking in the spirit of humble obedience.

Every monk is faced with what Saint Benedict, in Chapter LVIII calls the dura et aspera, “the hard and rough” things by which one goes to God. The devil, knowing full well that nothing so alarms “the old man with his deeds” (Colossians 3:9) as the prospect of a lifetime of obedience, does everything he can to throw a man at the beginning of his monastic journey into a state of panic over it. If there are difficulties and struggles, Saint Benedict would have his monk “embrace them patiently with a quiet conscience, and not grow weary or give in” (Chapter LXVIII). Not for nothing is this very phrase of the Rule echoed in the magnificent Vespers hymn of the Common of Several Martyrs, Sanctorum Meritis:

The triumphs of the martyr’d saints

The joyous lay demand,

The heart delights in song to dwell

On that victorious band:

Those whom the senseless world abhorr’d,

Who cast the world aside,

Deem’d fruitless, worthless, for the sake

Of Christ, their Lord and Guide.

For Thee they braved the tyrant’s rage,

The scourge’s cruel smart;

The wild-beast’s claw their bodies tore,

But vanquish’d not the heart:

Like lambs before sword they fell,

Nor cry nor plaint exprest;

For patience still’d the conscious mind,

And arm’d the fearless breast.

There are men who fear obedience more than “the scourges cruel smart and the wild beast’s claw.” Saint Benedict says that one should embrace the hard and contrary things of obedience “patiently with a quiet conscience, and not grow weary or give in.” We, all of us, tend to push away, or to put off, things that we find hard and contrary. Saint Benedict says that the monk is to embrace them with a quiet conscience. Tacite conscientia patientiam amplectatur. What is this quiet conscience? It is the silencing of all one’s fears, apprehensions, morbid ruminations, and resentments. “Why should I do this thing? What if I become fatigued, or sick, or anxious, or stressed? Why ought I do this thing now? I can put it off until tomorrow? The last time I had to so this, it was too difficult. Ah, here is something else more interesting and more to my liking. I shall do this thing first and try not to think about the thing that I fear doing.” The monk who holds such conversations with himself in his head is not quieting his mind to embrace obedience; he is, rather, filling his consciousness with noisy thoughts contrary to obedience. To such as these, Saint Benedict offers the tonic of Sacred Scripture, saying: “He that shall persevere to the end shall be saved” (Matthew 24:13). And again: “Let thy heart be comforted, and wait for the Lord” (Psalm 26:14).

The young Dublin priest, Father Joseph Aloysius Marmion, entered the monastery precisely because he understood that obedience was the one thing lacking in his otherwise good life, and because he craved obedience above all else. Years after making profession of obedience as a monk, and struggling to live what he had professed, Abbot Marmion would write:

Full submission to the Superior and to the Rule is for the monk the way that leads most surely to God, because a like humble and constant submission in all things, such as our Holy Father requires, closes every outlet to bad habits and opposes them till in the end they are destroyed. Perfect obedience is the most authentic means for the monk of purifying himself to the innermost depths of his being. A monk who obeys perfectly, in the spirit indicated by the Rule, will quickly arrive at complete freedom from every trammel which holds him back from God. At the same time, he advances in virtue which, becoming stronger, renders him more pliant under the Holy Spirit’s action.

Blessed Marmion even gives a prayer, in Christ the Ideal of the Monk, for one who, in spite of the struggles inherent in obedience, desires nonetheless to be obedient. This is his prayer:

My God, I have come here to seek Thee ; for love of Thee, I have left all things ; I come to lay at Thy feet my independence, my liberty ; I promise Thee to submit myself to a superior, to obey him in everything, however contrary to my tastes and ideas his command may appear to me.

Abbot Marmion experienced prayer as a conversation with God, not as a monologue. And so he tells us how God answers such prayer. “God”, he writes, “says to us on His side”:

I promise you, despite the weaknesses or even the errors of the one who represents Me towards you, to direct you at each step of your life, and to bring you, through him, to the one thing necessary that you seek: perfect love and the most intimate union with Me.

Dom Marmion wrote in a letter in 1888, when he was but two years in the cloister: “I got light to understand that obedience is everything for a Benedictine”. Some find this affirmation excessive, but Dom Marmion explains:

All the evils which have afflicted humanity, destroyed God’s work, and filled hell, come from one act of disobedience. All the graces obtained for us by Jesus Christ are due to His obedience.

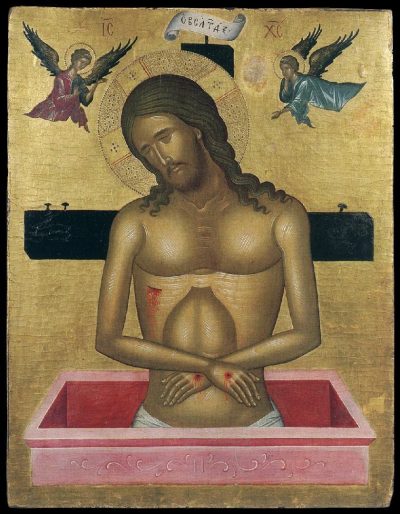

The monk vowed to obedience, and living what he has vowed, shares in the work of redemption. Obedience yokes a monk to Christ. Father Joseph Marmion left his successful ministry as a priest of the diocese of Dublin not so much for the grace of the Benedictine liturgy as celebrated at Maredsous (this would be a later discovery for him) as for the bonum obedientiae, the opportunity offered him by Benedictine life to enter concretely, hour after hour and day after day, into the obedience by which Christ wrought the great work of redemption.

For a son of Saint Benedict, then, obedience is not primarily a tactical necessity: a means to getting a job done efficiently. Nor is obedience primarily an ascetical practice: a way of mortifying one’s disordered impulses and harnessing one’s passions. Nor is it a social convention: a way of keeping men who live under the same roof in some kind of functional harmony. For the Benedictine monk, obedience is sacramental: a way of being united to Christ in His saving Passion and in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. Every act of obedience is a kind of communion; knowing this makes every act of obedience desirable and precious. This is why Blessed Columba Marmion wrote so compellingly of the bonum obedientiae, the good thing that is obedience. The smallest act of obedience, freely undertaken, as Saint Benedict says, “for the love of God, trusting in His assistance” (Chapter LXVIII), is good because it gives me Christ and unites me to Him.