Of the Discipline of saying the Divine Office (XIX)

CHAPTER XIX. Of the Discipline of saying the Divine Office

24 Feb. 26 June. 26 Oct.

We believe that the Divine presence is everywhere, and that the eyes of the Lord behold the good and the evil in every place. Especially should we believe this, without any doubt, when we are assisting at the Work of God. Let us, then, ever remember what the prophet saith: “Serve the Lord in fear”; and again, “Sing ye wisely” and, “In the sight of the angels I will sing praises unto Thee.” Therefore let us consider how we ought to behave ourselves in the presence of God and of His angels, and so assist at the Divine Office, that our mind and our voice may accord together.

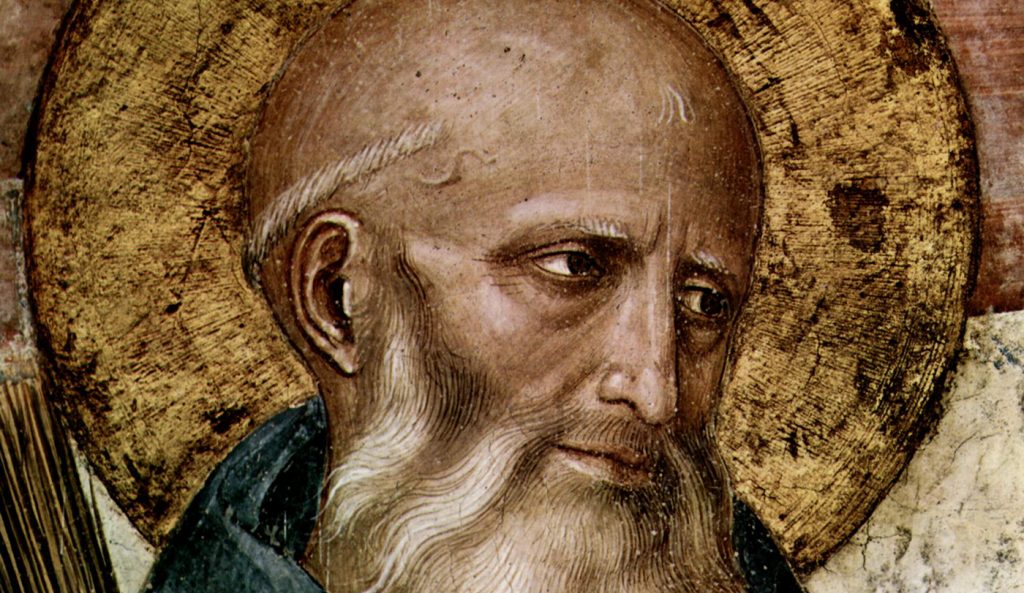

Saint Benedict tells us that the Divine presence is everywhere. In the Bible, “presence” and “Face” are synonymous. To seek the Face of God is to seek His presence. We ask God to turn His Face towards us; that is, to envelop us in His presence. One who is in the presence of God abides beneath His gaze. The Greek πρόσωπον (prosopon) means person, and face, and personal presence. Saint Benedict would have us understand that when we chant the Divine Office we are held in the Divine gaze, we are bathed in the radiance of His Face, we are summoned into relationship with the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Ghost. The relationship with God, like every deep human relationship, begins in the face–to–face and leads to the heart–to–heart.

For God, who commanded the light to shine out of darkness, hath shined in our hearts, to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God, in the face of Christ Jesus. (2 Corinthians 4:6)

Saint Benedict speaks next of the “eyes of the Lord”. What is a face without eyes? It is an inscrutable mass of flesh. To make “eye contact” with another is open oneself to the possibility of interpersonal communion. The eyes of the Lord are, at every moment and in every place, fixed upon us, taking in even our most secret thoughts.

Lord, I lie open to thy scrutiny; thou knowest me, knowest when sit down and when I rise up again, canst read my thoughts from far away. Walk I or sleep I, thou canst tell; no movement of mine but thou art watching it. Before ever the words are framed on my lips, all my thought is known to thee; rearguard and vanguard, thou dost compass me about, thy hand still laid upon me. Such wisdom as thine is far beyond my reach, no thought of mine can attain it. Where can I go, then, to take refuge from thy spirit, to hide from thy view? If I should climb up to heaven, thou art there; if I sink down to the world beneath, thou art present still. If I could wing my way eastwards, or find a dwelling beyond the western sea, still would I find thee beckoning to me, thy right hand upholding me. Or perhaps I would think to bury myself in darkness; night should surround me, friendlier than day; but no, darkness is no hiding-place from thee, with thee the night shines clear as day itself; light and dark are one. (Psalm 138:1–12)

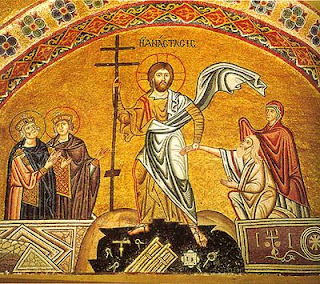

The gaze of God is fixed upon us everywhere; when we assist at the Divine Office, however, the gaze of God envelops us with a particular intensity. The liturgical gaze of God is that by which the Father contemplates the Son and takes delight in Him, even as He did on Mount Thabor at the Transfiguration. The liturgical gaze of God is transfiguring; it is revealed in the mysterious bright cloud:

And as he was yet speaking, behold a bright cloud overshadowed them. And lo, a voice out of the cloud, saying: This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased: hear ye him. And the disciples hearing, fell upon their face, and were very much afraid. (Matthew 17:5–6)

Saint Benedict further says that we are to “serve the Lord in fear” (Psalm 2:11). One must understand that “to serve” means “to worship”. In the Bible, to serve God is to offer him the sacrificial cultus of latria, that is the adoration due to God alone. The son of Saint Benedict is, as Dante says, disposto a sola làtria (Paradiso, Canto XXI), for latria alone set apart. The fathers of the Second Vatican Council understood this when they decreed that, “the principal duty of monks is to offer a service to the divine majesty at once humble and noble within the walls of the monastery” (Perfectae caritatis, 9).

Saint Benedict enjoins us to sing in such as way as to taste the Word of God: psallite sapienter (Psalm 46:8). God so created man that he has, in addition to the palate in his mouth that allows him to taste various foods, the palate of the soul by which he can savour the Word of God. The psalmody of the Divine Office is just this: verse after verse of the Word of God tasted in all its sweetness, and then offered back to God whence it comes.

So shall my word be, which shall go forth from my mouth: it shall not return to me void, but it shall do whatsoever I please, and shall prosper in the things for which I sent it. (Isaias 55:11)