Hearken, O my son

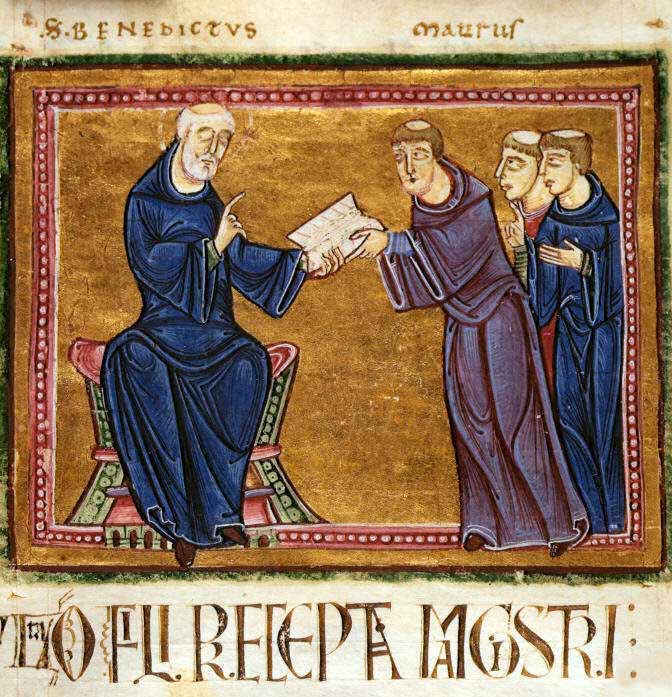

PROLOGUE OF OUR MOST HOLY FATHER SAINT BENEDICT TO HIS RULE

1 Jan. 2 May. 1 SeptHearken, O my son, to the precepts of thy Master, and incline the ear of thine heart; willingly receive and faithfully fulfil the admonition of thy loving Father, that thou mayest return by the labour of obedience to Him from Whom thou hadst departed through the sloth of disobedience. To thee, therefore, my words are now addressed, whoever thou art that, renouncing thine own will, dost take up the strong and bright weapons of obedience, in order to fight for the Lord Christ, our true king. In the first place, whatever good work thou beginnest to do, beg of Him with most earnest prayer to perfect; that He Who hath now vouchsafed to count us in the number of His children may not at any time be grieved by our evil deeds. For we must always so serve Him with the good things He hath given us, that not only may He never, as an angry father, disinherit his children, but may never, as a dreadful Lord, incensed by our sins, deliver us to everlasting punishment, as most wicked servants who would not follow Him to glory.

Today is a new beginning for each of us, a moment of grace, an opportunity to be converted once again to the life for which we first came to the monastery. In the very first words of the Holy Rule, our father Saint Benedict sets the tone for all that will follow. Using the second person singular, he addresses each one of us incisively: Obsculta, o fili, “Hearken, O my son”. It was customary, in ancient times, to call the catechumens preparing for Baptism audientes, that is, “those who listen”. The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus prescribes: “Let catechumens spend three years as hearers of the word” (Apostolic Tradition, 17). For Saint Benedict, a man comes to the monastery to be a hearer of the Word. How can one not recall here the words of Saint Augustine?

Be not foolish, O my soul, nor become deaf in the ear of thine heart with the tumult of thy folly. Hearken thou too. The Word itself calleth thee to return. (Confessions, Book IV)

For Saint Benedict, and for all who claim to be his sons, the Word is not a text; the Word is God–Revealing–God. The Word is God–Uttering–Himself. Every utterance of God is an inpouring of grace, a communication of divine life, the principle of a new creation. “It follows”, says Saint Paul, “that when a man becomes a new creature in Christ, his old life has disappeared, everything has become new about him” (1 Corinthians 5:17). Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity, though not a Benedictine, captures the sense of this perfectly when, in her splendid prayer, she says:

O Eternal Word, utterance of my God, I want to spend my life listening to you, to become totally teachable so that I might learn all from you.

It is likely that Saint Benedict had in mind the words of Deuteronomy 6:4: Audi, Israël: Dominus Deus noster, Dominus unus est, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord”, the intonation of the most important daily prayer of the pious Jew. This, in turn, resonates with the words of Saint Paul” “And whosoever shall follow this rule, peace on them, and mercy, and upon the Israel of God” (Galatians 6:16).

One does not come to the monastery, presuming to know what is required. One enters the monastery with an open heart, eager to become “totally teachable”. One newly–come to the monastery offers one’s heart to the Finger of God’s Right Hand, the Holy Ghost, as a clean, fresh tablet upon which He will inscribe the Word of Life in letters of fire. The humble man readily inclines the ear of his heart because he knows that he has everything to learn. One who comes to the monastery with years of theological study and of extensive reading behind him — especially the postulant who has been in seminary or is a priest — is sometimes at a disadvantage, because he can too quickly assume that he already knows all that he needs to know. The son of Saint Benedict, from the first day of life in the monastery until the hour of his death must have no other ambition than to be numbered among the very little ones for whom Our Lord praises His Father:

I confess to thee, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them to little ones. Yea, Father; for so hath it seemed good in thy sight. (Matthew 11:25–26)

Many have sought to clarify the identity of the Master in the first phrase of the Prologue: “Hearken, O my son, to the precepts of thy Master”. Saint Benedict deliberately leaves the Master anonymous, and this because the Master represents the voice of the whole monastic tradition. The Master is, at once, the voice of Saint John Cassian, the voice of all the Desert Fathers, the voice of Saint Basil, and of all those whom, in the last chapter of the Rule, Saint Benedict calls simply “the holy Catholic Fathers”. Saint Benedict may be inspired here by the Admonition to a Spiritual Son attributed to Saint Basil, in which we read:

These words — we read — do not come from me, but spring from the divine wellsprings. We do not present you with a new doctrine, but with the one that I have received from my fathers.

Saint Benedict makes no claim of originality. On the contrary, Saint Benedict seeks only to hand on what he himself received from his fathers and masters in the monastic life. The Holy Rule is an initiation into the purest monastic tradition. Saint Aelred expresses this in one of his sermons for the feast of Saint Benedict:

Benedict was filled not only with the spirit of Moses [Moses being the Legislator]; he was also, somehow, as someone said, filled with the spirit of all the just. He built a spiritual tabernacle from the offerings of the children of Israel. In his Rule sparkles the gold of blessed Augustine, the silver of Jerome, the double–dyed purple of Gregory, not to mention the jewel–like sayings of the holy Fathers. (Sermon VIII, For the Feast of Saint Benedict)

Saint Benedict would have us understand that the monastic apprenticeship is necessarily the transmission of a living flame from the spiritual father to his son, and from the master to his disciple. The essential requirement is, as Saint Benedict says, that the son, the disciple, incline the ear of his heart; that he willingly receive and faithfully fulfil the admonition of the father who is, but another living link in the long chain of the monastic tradition, so as to return by the labour of obedience to God from Whom, through the sloth of disobedience, he has become estranged. Why is the return to God made by the labour of obedience? Saint Augustine, I think, helps one to understand this when, in The Confessions, he says:

I was far from Your face, through my darkened affections. For it is not by our feet, nor by change of place, that we either turn from You or return to You. (Confessions, Book I, Chapter XVIII)

One returns to God as one departed from God — not by foot, nor by automobile, nor by train, or ship, or aircraft — but by a movement of the heart. At bottom, disobedience, the first movement of all sin, is a closing of the ear to the voice of Christ, and a turning of the heart away from His face. Once one has turned away into the “far country” of the prodigal son, into the “land of unlikeness”, it is difficult to turn back because, in turning away, one becomes disoriented, all becomes dark, the familiar landmarks disappear, one loses oneself in the stormy night. In such a state it is necessary to take the outstretched hand of a trusted guide, to listen to his directions, and to walk with him, humbly, all the way back to the Father’s house. In so doing, one discovers that one is part of a vast movement of return to God, of the immense pilgrimage of “the generation of them that seek Him, of them that seek the face of the God of Jacob” (Psalm 23:6). This movement is what we call the monastic tradition. Saint Benedict, our father, teacher, our legislator, guides us into this tradition. To be a Benedictine is to be a son of tradition.