Totis visceribus diligebat Christum regem

The title of today’s entry is from the Magnificat Antiphon:

The title of today’s entry is from the Magnificat Antiphon:

O how blessed a bishop was he! His inmost heart of hearts yearned on the King Christ, and he had no dread for the power of the Empire! O how holy a soul was his, which passed not away by the sword of the persecutor, and yet lost not the palm of martyrdom.

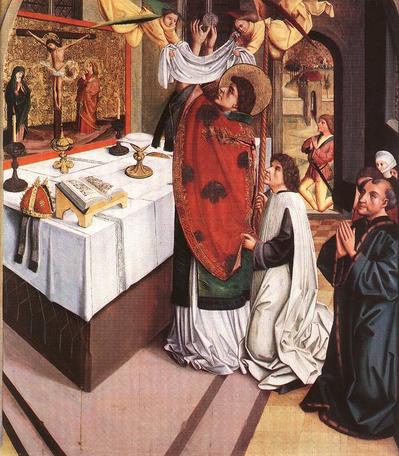

This wonderful painting, so rich in liturgical details — look at the gorgeous chasuble — depicts a famous episode in Saint Martin’s life. One day, as he prepared to offer the Holy Sacrifice, Bishop Martin caught sight of a poor beggar in need of clothing. Immediately, he ordered his attending deacon to provide the beggar with a suitable garment. Seeing that the deacon was in no hurry to obey his order, Martin removed his tunic and gave it to the beggar. Later, at Holy Mass, a globe of fire appeared above his head. At the elevation of the Sacred Host, the sleeves of Bishop Martin’s alb fell back baring his arms. Straightaway two angels appeared and, with a precious cloth, covered the prelate’s arms for the duration of the elevation. The beggar (in the foreground, clothed in Martin’s black tunic) and the other faithful looked on in wonder.

The Soldier Announces the Advent of the King

Today’s Holy Gospel, focusing on judgment and on the arrival of the Bridegroom-King in glory with all his angels, is perfectly adapted to the eschatological impetus given to the liturgy between All Saints Day (November 1st) and the First Sunday of Advent. In other parts of the Catholic world, a six-week Advent begins on the Sunday following the feast of Saint Martin. This is the tradition of the Church of Milan, for example. The arrival of Martin the soldier announces the arrival of Christ, the true King, the Lord of glory.

The Confession of Saint Martin

Saint Martin of Tours was the first non-martyr to be honoured with a liturgical cult, the first of a long line of “confessors” to make their way into the Church’s calendar. The Invitatory Antiphon refers to today’s feast as “Saint Martin’s confession.” Confession here refers both to the saint’s profession of the Catholic faith unto death, and to his praise of God. The Magnificat Antiphon will have us sing: “Though he did not die a martyr’s death, this holy confessor won the martyr’s palm.” The magnificent hymn Iste Confessor, sung today at Matins and Vespers, was composed for the feast of Saint Martin.

Benedictines have a tradition of devotion to Saint Martin: Holy Father Benedict dedicated a chapel to Saint Martin at Monte Cassino. Franciscan liturgists of the Middle Ages borrowed from the Office of Saint Martin in composing the liturgy for the feast of Saint Francis, in many cases simply changing Martinus to Franciscus.

The Holy Ghost guided Saint Martin through a succession of states of life. There is Martin the soldier, Martin the catechumen, Martin the monk, and finally, Martin the bishop. this may account for his astonishing popularity. While in North America, Saint Martin is often forgotten, in France, over five hundred villages and over four thousand parishes bear his name and witness to the enthusiastic piety stirred up by his memory. In France and in Italy, Martin (the name of Saint Thérèse), and Martino (my grandmother’s name), are common surnames.

Martin the Merciful

The lesson from the prophet Isaiah presents Saint Martin as one filled with the Holy Spirit, as one anointed and sent to bring good news to the poor. Martin binds up broken hearts, comforts those who mourn. He puts praise in the mouths and hearts of the despondent. The Life of Saint Martin by Sulpicius Severus recounts Martin’s miracles of compassion, conversion, generosity, and healing. Together with Saint Athanasius’ Life of Saint Antony, the Life of Saint Martin became the standard reference for the biographers of holy men.

The Poor Christ

Saint Paul had his blinding light on the road to Damascus; Saint Martin encountered Christ in the person of a poor beggar. Drawing his sword, Martin cut his ample military cloak in two and covered the beggar with half of it. The following night he was rewarded with an apparition of Our Lord, clothed in the same half- cloak.

The whole liturgy today evokes the cloak divided by a sword and given to Christ. A wondrous exchange! Saint Martin clothes the poor Christ with his cloak; Christ clothes the poor Martin with glory. “You know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor, so that by His poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor 8:9). The words of the holy gospel: “I was naked and you clothed me” become “You, Martin, were naked and I clothed you.” We celebrate Martin, clothed with grace and with glory by the humble beggar, Christ, whom he had clothed by cutting his prestigious Roman military cloak in half with his sword: the sacrifice of his pride.

Divinely Disproportionate

The naked Christ is all around us waiting to be clothed in whatever remnants our pride will yield to the sword of sacrificial love. In the absence of a sword, a mere pin will do! The paradox is that in clothing the Beggar, we become the beggar, and the Beggar becomes the one who clothes us in a mantle of justice, of grace and of glory. Is not the teaching of that other Martin, Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face? The smallest gesture of sacrificial love on our part unleashes a torrent of transforming love on the part of God. There is no equality here; there cannot be. Fair exchange is utterly foreign to the Kingdom of God. “If a man offered for love all the wealth of his house, it would be utterly scorned” (Ct 8:7). The divine response is always magnificently disproportionate to the tiny human gesture.

The Holy Sacrifice

Nowhere is this truer than in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. The Mass of the Catechumens (Liturgy of the Word) stirs us to respond in some way to God, Who, in speaking, already gives Himself, and communicates to us His life, His love, and His light. Is this not the prayer of the priest before receiving the Precious Blood: “What shall I render to the Lord for all His bounty to me? I will lift up the cup of salvation and call on the name of the Lord” (Ps 115:12-13)?

Suscipe Me

How do we respond? What do we bring to the altar? A little bread, a little wine, a drop of water: poor and humble symbols of ourselves, our life, our work, our joys, and our sufferings, but especially of our desire to, as Blessed Michael Iwene Tansi put it, “to belong entirely to God.” What is the bread on the paten, the wine mixed with water in the chalice, if not a silent cry to the living God: Take me! Suscipe me? I surrender to the priestly hands of the Son; I yield to the mysterious action of the Paraclete. I offer myself to the two hands of the Father — the Son and the Holy Spirit — that by them, my poverty might become an oblation pleasing in the Father’s sight.