And never to despair of God’s mercy

Bless the Lord, O my soul, and never forget all he hath done for thee. Who forgiveth all thy iniquities: who healeth all thy diseases. Who redeemeth thy life from destruction: who crowneth thee with mercy and compassion. (Psalm 102:2–4)

On this Feast of All Saints of the Benedict Order, the media are giving attention to the alleged mistakes of an abbot who, it appears, fell prey to the passions, appetites, and weaknesses that threaten every man. Four things must, I think, be kept in mind when confronted with “news” of this sort.

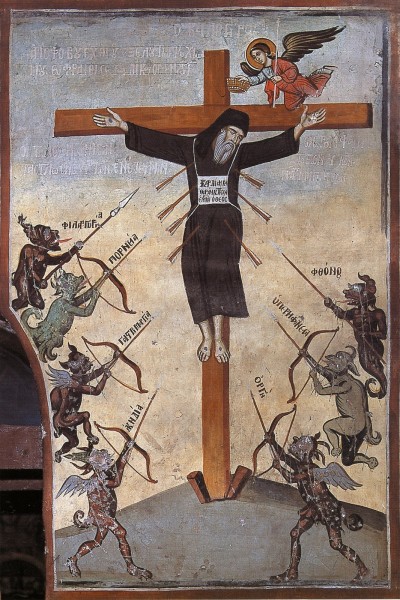

I. The powers of darkness set their sights on monks, and on priests in particular. The closer one is to the altar the more one is surrounded by demons who, day and night, devise schemes to bring about the downfall of the elect of God. The icon of the Crucified Monk is not a bit of Byzantine hyperbole. It is an accurate portrayal of reality. “A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among robbers, who also stripped him, and having wounded him went away, leaving him half dead” (Luke 10:30). The media do tend to kick a man when he is down; if they lift him up, it is only to expose him to ridicule, all the while feigning a sanctimonious shock and horror. Priest and levite pass by, not wanting to appear, in any way, compromised by association with one so humiliated and shamed.

I am poor, and in labours from my youth: and being exalted have been humbled and troubled. Thy wrath hath come upon me: and thy terrors have troubled me. They have come round about me like water all the day: they have compassed me about together. Friend and neighbour thou hast put far from me: and my acquaintance, because of misery” (Psalm 87:16–19).

In Our Lord’s parable, it is the Samaritan who responds mercifully, becoming in his deeds and words an epiphany of the Heavenly Father’s compassion:

But a certain Samaritan being on his journey, came near him; and seeing him, was moved with compassion. And going up to him, bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine: and setting him upon his own beast, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And the next day he took out two pence, and gave to the host, and said: Take care of him; and whatsoever thou shalt spend over and above, I, at my return, will repay thee. (Luke 10:33–35)

II. The arsenal of a monk’s defence is found in Chapter IV of the Holy Rule, “The Instruments of Good Works”. The older I become the more do I appreciate the wisdom contained in Chapter IV. The man who employs Saint Benedict’s seventy–four instruments of good works may experience the arrows of the enemy shot from every side and whizzing past him but, even if they graze his skin, provoking alarm and causing irritation, they will not wound him mortally. A monk may not able to wield all the instruments of good works at one time. He may, for want of practice, use some of them awkwardly. He may find others momentarily unsuitable. He keeps them all, nonetheless, at the ready and in good order. The one instrument from which a monk must not separate himself, even for a moment, is the last one of all, the 74th: Et de Dei misericordia numquam desperare. And never to despair of God’s mercy.

III. Spectacular falls from grace do not happen randomly. They are the result of an accumulated quantity of seemingly insignificant compromises with the world, the flesh, and the devil. Again, Chapter IV of the Holy Rule is a comprehensive inventory of the things that, on the one hand, lead to virtue and, on the other, lead to vice. One who sees a brother withdrawing from prayer and isolating himself from the acies fraterna, the fraternal battle line (Holy Rule, Chapter 1) has an obligation humbly and respectfully to admonish him, even when the wavering brother holds a position of authority. Those in positions of authority, precisely because they are in some way isolated by their office, are at greater risk of losing what David calls “a right spirit” (Psalm 50:12).

IV. Always there is mercy. Saint Benedict was thoroughly acquainted with the moral and physical infirmity of those in his care. Nowhere, when treating of human weakness, does Saint Benedict manifest an attitude of priggish condemnation: his response is that of the wise and compassionate physician who has but one thing in view, the cure of the sin–sick soul. No one is dispensed from the obligation to pray for a brother fallen in spiritual combat, even more, to pray in his name, representing him before the Face of Christ until such time as the fallen brother is strong enough to drag himself into the presence of the Lord, there to groan, and weep, and bear his breast, saying “God, be merciful to me a sinner” (Luke 18:13). In Benedictine life every year is a year of mercy for, even on one’s darkest days, in the face of spectacular falls from grace, there remains Saint Benedict’s wisest word: “And never to despair of God’s mercy” (Holy Rule, Chapter IV: 74).