Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 4

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Letter 4: Flynn

Dear Flynn,

I shall pick up where I left off yesterday. Each of your questions merits a thoughtful response. The Benedictine ethos, if one can speak of such a thing, eschews a “one size fits all” approach to life. Not only is there an astonishing diversity among the brethren of the same community; there is an equally astonishing diversity among monasteries living under the same Holy Rule. Many things shape a monastery’s development: the ethnicity of the founders, the historical context, the life of the Church, pronouncements of the Magisterium, and, even, the currents of popular piety that, over time come to bear upon a community’s reading (or hermeneutic) of the Holy Rule.

I have known, in the past, more than one monk who claimed with a kind of ingenious chauvinism that his abbey (or his monastic Congregation) was the only one living the Rule of Saint Benedict authentically. I remember very well the day, many years ago, when a certain monk, speaking of the Congregation to which his abbey belonged, said to me with utmost sincerity: “We alone are authentic Benedictines”. He said this without a trace of irony. Reading the Sayings of the Desert Fathers is a suitable remedy for this kind of monastic chauvinism.

One day Abba Isaac went to a monastery. He saw a brother committing a sin and he condemned him. When he returned to the desert, an angel of the Lord came and stood in front of the door of his cell, and said, ‘I will not let you enter.’ But he persisted saying, ‘What is the matter?’ and the angel replied, ‘God has sent me to ask you where you want to throw the guilty brother whom you have condemned.’ Immediately he repented and said, ‘I have sinned, forgive me.’ Then the angel said, ‘Get up, God has forgiven you. But from now on, be careful not to judge someone before God has done so.’

Abba Joseph said, “If you want to find rest here below, and hereafter, in all circumstances say ‘Who am I?’ and do not judge anyone.

A brother questioned Abba Poemen saying, “If I see my brother committing a sin, is it right to conceal it?” The old man said to him, “At the very moment when we hide our brother’s fault, God hides our own and at the moment when we reveal our brother’s fault, God reveals ours too.”

There is, of course, a legitimate and healthy pride in the heritage of a monastery, in the spiritual patrimony that has been passed down from one generation of monks to another. There is also the danger of looking down one’s nose at any expression of Benedictine life that does not measure up to one’s own standards or correspond to one’s ideal. Monks can be peculiar fellows. Allow me to tell you a story:

At an international meeting of Benedictines, there were some monks who had confidence in themselves, thinking they had won acceptance with God, and despised the rest of the monastic world. To these monks a very old abbot — one who had lived through wars, persecution, poverty, sickness, and slander — addressed this parable: Two monks went up into the church of Monte Cassino to pray; one was a refined rigorist of the strict observance, the other a poor soul whose life was marked by instability and weaknesses of all sorts. The first stood upright before the altar, and made this prayer in his heart: “I thank thee, Saint Benedict, that I am not like the rest of monks, who do not rise for the night Office, who eat meat, and go about without a proper tonsure, who are ignorant of the liturgy that is the glory of our great Order, who live in monasteries of architectural mediocrity, who fail to appreciate the finer points of Gregorian Chant, or like this poor fellow here, who, from what I’ve heard, has a very chequered past; for myself, I fast from September 14th until Easter, I rise daily for the night Office, I write books that have won acclaim in high places, I publish learned essays that bring glory to the Order, and I, for all of that, I have never missed saying a single Little Hour”. And the other monk stood far off; he would not even approach the altar of the great church; he only beat his breast, and said, “O God, keep me from ever despairing of Thy mercy”. I tell you, this man went back home to his poor little monastery higher in Saint Benedict’s favour than the other. Everyone who exalts himself shall be humbled, and the man who humbles himself shall be exalted.

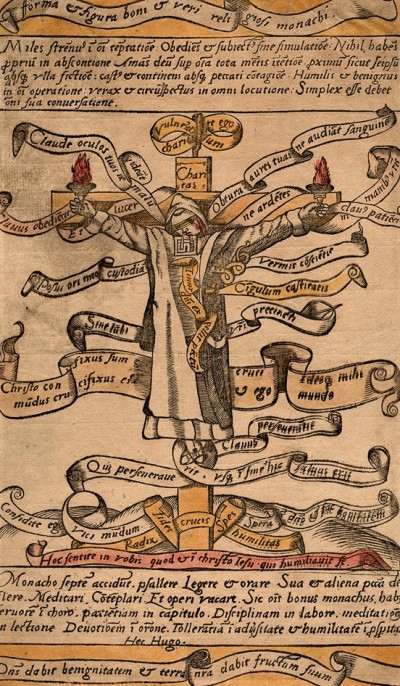

I suppose, dear Flynn, that monasteries will always have a smattering of ideologues, chauvinists, rigorists, rubricists, and esthetes, but the vast majority, the rank and file of Saint Benedict’s sons will, I think, be men of obedience, silence, and humility, men who truly seek God, who love the Divine Office, who find their daily sustenance in the Word of God, who love their abbot and one another. Chapter 72 of the Holy Rule remains the critical reference:

As there is an evil zeal of bitterness, which separateth from God, and leads to hell, so there is a good zeal, which keepeth us from vice, and leadeth to God and to life everlasting. Let monks, therefore, exert this zeal with most fervent love; that is, “in honour preferring one another.” Let them most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of mind. Let them vie with one another in obedience. Let no one follow what he thinketh good for himself, but rather what seemeth good for another. Let them cherish fraternal charity with chaste love, fear God, love their Abbot with sincere and humble affection, and prefer nothing whatever to Christ. And may He bring us all alike to life everlasting.

The best way to discover where God is calling you, Flynn, is to know yourself. You must not try to force yourself into some pre–conceived ideal of monastic observance that, in the end, will leave you exhausted and despondent. A man who seeks to practice Benedictine discretion takes the measure of his own strengths and weaknesses, and the measure of the “hard and arduous things” (Rule, Chapter 58) that lie before him and, then, relying on the grace of Christ, goes forward, as Saint Benedict says, “with a good will, because God loveth a cheerful giver” (Rule, Chapter 5). Saint Benedict gets it right when, in writing of the abbot, in Chapter 64, he says:

In the works which he imposeth, let him be discreet and moderate, bearing in mind the discretion of holy Jacob, when he said “If I cause my flocks to be overdriven, they will all perish in one day.” Taking, then, the testimonies, borne by these and the like words, to discretion, the mother of virtues, let him so temper all things, that the strong may have something to strive after, and the weak nothing at which to take alarm.

I have known men who seem to flourish in highly institutionalised environments: a large community, precise rules for behaviour in all circumstances, a very formal style. Some men prefer such communities because there is a certain security in having clear–cut prescriptions for every minute of the day. The risk is that there can be a major emotional and spiritual crack–up when the mid–life crisis hits and shatters all one’s certainties, leaving one sitting in the puddle of one’s misery with mud splattered all over one’s face. This, however, can be a great grace!

Other men flourish in smaller, more familial communities characterised by closer bonds of charity between the Father and his sons, and among the brethren. In such communities the formation given is more personal. The way of life is demanding (God knows!) but less formalistic. There are more surprises, and there is a need for flexibility. Silverstream would fit this description. The grace of such communities is, I think, the wondrous discovery that the merciful grace of Christ is deployed in weakness. Moral perfectionism can be an obstacle to that discovery.

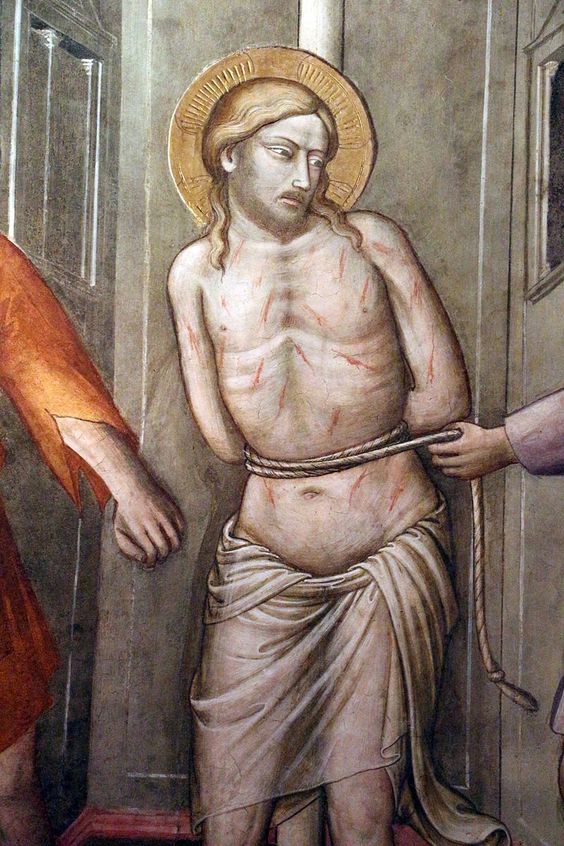

Each Benedictine monastery has its own special identity and characteristics. At Silverstream, we find in the Sacred Host the divine icon of what a monk is called to be: hidden, obedient, silent, humble, and, at every moment, made over the Father in a state of sacrificial victimhood. The Holy Mother of God is present to us everywhere and in all circumstances; we take to heart the “Ecce mater tua” (Behold thy mother) that Our Lord uttered from the Cross, and so relate to the Virgin Mary as the Mother of the monastery. Life at Silverstream is a daily challenge, an adventure of faith marked, as all new foundations are, by conditions of poverty, insecurity, and limitations of all sorts.

You tell me, Flynn, that you have been asking advice of friends of yours in the diocesan clergy. There are many wise and holy men among those priests who labour heroically in the vineyard of the Lord. When it comes to the monastic life, however, most of them — not all of them — are out of their depth. I cannot tell you the number of men who have come to me, thinking they have a monastic vocation, because their parish priest or a spiritual director in the seminary said something along the lines of . . . “You strike me as an introverted lad. You’re artistic. You like being alone. You seem not to have a lot of social energy. You have an amazing knowledge of rubrics. You’re really into the liturgy. You’re a real bookworm”. And then, the good man adds, “You would make a brilliant Benedictine!” God help us! None of these traits are an indication of a Benedictine vocation.

It is not wise to take counsel of people (even of priests) who have no experience of monastic life. Very often their vision of the Benedictine reality is clouded by reason of too romantic a notion of what is the heart of the monastic vocation, or by certain subjective prejudices. More than one monastic vocation has been ruined by listening to the vain speculations of outsiders — monastic tourists — who have never put their lives on the line by actually taking the plunge. If one is thinking of marriage, one does well to take advice of a happily married mature man who has paid the price, not of a chap who observes marriage from the sidelines. There are far too many “monastic tourists” who view things from the safety of the sidelines.

Take time to pray and reflect, Flynn, but not too much time. The sands of time run out quickly. “Today if you shall hear his voice, harden not your hearts” (Psalm 94:8). In less than five years, Flynn, there will be thirty candles on your birthday cake. I’m reminded of Paddy, the lad from County Cavan, who couldn’t decide if he wanted to marry Brigid, or Molly, or Susan, or Kathleen. In the end, he waited so long that all four girls got on with their lives and married other lads, and Paddy found himself too old, too set in his ways, and too afraid of the unknown to risk anything. He spent the rest of his life between his flat, his job, his pub, and (thank God) his parish church: a sad little man, full of regrets over what might have been. Of one thing, I am certain, Flynn: it is that Our Lord has a stupendous plan for your life. Did He not say, “I am come that they may have life, and may have it more abundantly?” (John 10:10). Place yourself unconditionally in Our Lady’s hands; it is the best way of opening yourself to the light of the Holy Ghost. Ask for the intercession of our father Saint Benedict.

With my blessing,

Father Prior