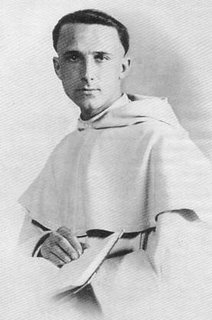

Père Garrigou-Lagrange on Psalmody

Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s remarkable teaching on liturgical prayer in The Three Ages of the Interior Life is a suitable complement to yesterday’s post on psalmody. The subtitles in boldface are my own.

The Psalmody of the Divine Office: The Great Prayer of the Church

One of the greatest means of union with God for the religious soul is the psalmody, which in religious orders is the daily accompaniment of the Mass. The Mass is the great prayer of Christ; it will continue until the end of the world, as long as He does not cease to offer Himself by the ministry of His priests; as long as from His sacerdotal and Eucharistic heart there rises always the theandric act of love and oblation, which has infinite value as adoration, reparation, petition, and thanksgiving. The psalmody of the Divine Office is the great prayer of the Church, the spouse of Christ; a day and night prayer, which ought never to cease on the surface of the earth, as the Mass does not.

A School of Contemplation, of Self Oblation, of Holiness.

For those who have the great honor to take part in the chant, the psalmody should be an admirable school of contemplation, of self oblation, of holiness. That it may produce these abundant fruits, the psalmody should keep what is its very essence; it ought to have not only a body which is well organized according to harmonious rules, but also a soul. If it ceases to be the great contemplative prayer, it gradually loses its soul and, instead of being a soaring, a rising toward God, and a repose, it becomes a burden, a source of fatigue, and no longer produces great fruits. Therefore we shall discuss briefly first of all deformed and materialized chant, then true psalmody, which is a deliverance, like the chant of the Church, above all the noises of earth.

Deformed Psalmody: A Body Without a Soul

Deformed psalmody is a body without a soul. Generally, it is marked by unseemly haste, as if undue haste, which, according to St. Francis de Sales, is the death of devotion, could replace true and profound life. The words of the Office are badly pronounced without rhythm or measure. The antiphons, which are often beautiful, are poorly said and become unintelligible, the hymns even more so. The lessons which are not punctuated as they should be, are read as one would read the most indifferent or even the most boring passages, when, as a matter of fact, they are concerned with the splendors of divine wisdom or what is most beautiful in the lives of the saints. People wish to save time, four or five minutes which they will devote to worthless trifles, and they lose the best of the time given by God. Father de Condren used to say: “If a master spoke to his servant as a number of people speak to God while saying the Divine Office, the servant would think that his master was insane to be jabbering in such fashion.”

As a result of haste, the psalmody of which we are speaking is mechanical and not organic; just as in a body without a soul, the members are no longer vitally united, but only placed together. The Office becomes a series of words following one another. The great meaning of a psalm is no longer comprehended; to one who is trying to grasp this meaning and to follow it, this mechanical chant brings fatigue and is an obstacle to true prayer.

Is this manner of chanting a lifting of the soul toward God? Perhaps, but it is a uniformly retarded elevation, like the movement of a stone that has been thrown into the air and tends to fall back; whereas true prayer ought, like a flame, to tend spontaneously toward heaven.

Remedies

What remedies can be applied to this evil? The remedy is to be found in recalling the rules for the chant. But this remedy is not effective if it alone is applied. The evil is deeper, and we must go to its roots. In reality, there is only one truly effective remedy that makes possible the utilization of the others: namely, the restoration of the spirit of prayer. Similarly, in order to restore functions to a body without a soul, life would have to be restored to it.

When the Heart Disengages from Choral Prayer

Deformed psalmody shows us that, for a soul which has no personal life of prayer, the recitation of the Office becomes altogether material, a wholly exterior worship. Not possessing the habit of recollection, this soul is assailed by thoughts foreign to the Office; its work, studies, or business affairs keep returning to its memory, and at times even thoroughly vain thoughts come. The most interior persons sometimes experience this distress. But in the case of those we are speaking of, it is a habitual state of negligence, and in them distraction does not remain in the imagination; it invades the higher faculties. How can anyone in this state taste the divine words of the psalms, the prophets, the Epistles, the most beautiful pages of the fathers and of the lives of the saints which are daily offered to us in the Divine Office? All these spiritual beauties remain unperceived like colorless and insipid objects. The great poetry of the Psalmist and the most profound cries of his heart become spiritless and monotonous.

Routine Mummifies the Liturgy

One day in choir, St. Bernard saw above each religious his guardian angel who was writing down the chant. The manner of writing differed greatly, however: some wrote in letters of gold, others in silver, while still others wrote with ink or with colorless water; one angel held his pen poised and wrote nothing. Routine mummifies the most profoundly living passages and reduces them to mechanically recited formulas. This manner of chanting is nothing but practical nominalism, a sort of materialism in action. The higher faculties do not live in a prayer made thus; they remain somnolent or scattered. A person may still hear the symphony of the Office, more beautiful than the most famous symphonies of Beethoven, but for lack of an interior feeling, he can no longer appreciate it. Often the Divine Office is studied from the historical point of view, or from the canonical point of view of strict obligations, and these distinctions are held to; but it is especially from the spiritual point of view that it must be considered and lived.

Contemplative Chant

What should the contemplative chant be? This chant is distinguished precisely by the spirit of prayer, or at least by the aspiration which inclines us to it, which desires it, seeks it, and at length obtains it. We are thus shown how much the contemplation of the mysteries of faith is in the normal way of sanctity: this contemplation alone can give us in liturgical prayer the light, peace, and joy of the truth tasted and loved, gaudium de veritate.

The spirit of prayer, more intimately drawn from mental prayer, is lost as soon as one hurries to finish daily prayer, as if it were not the very respiration of the soul, spiritual contact with God, our Life, It was in the spirit of prayer that the psalms were conceived without it, we cannot understand them or live by them. “As the hart panteth after the fountains of water, so my soul panteth after Thee, O God.”

The Pauses: Vital Rest Between Aspiration and Respiration

If the psalmody has this spirit, then in place of mechanical haste, which is a superficial life, we find profound life for which we do not need continually to recall liturgical rules, for these rules are merely the expression of its inner inclinations. Then, without excessive slowness the words are well pronounced, undue haste is avoided, and the pauses, serving as a vital rest between aspiration and respiration, are observed. The antiphons are tasted, and the soul is truly nourished with the substance of the liturgical text.

Psalmody and Mental Prayer

Whoever has the duty of reading the lessons, which are often most beautiful, should look them over ahead of time in order not to spoil their meaning. He who reads the lessons well avoids a too evident expression of his personal piety, but the great objective meaning of Scripture explained by the fathers remains intelligible, and here and there he grasps its splendors in the midst of its divine obscurities. No effort is made to save four or five minutes, and he ceases to lose the precious time given by God. He is even led at the end of the chant to prolong prayer by some moments of mental prayer, like the religious in bygone days who, at night after Matins and Lauds, spent some time in profound recollection. Many times in the history of their lives mention is made of these secret prayers, of this heart to heart conversation with God in which they often received the greatest lights, which made them glimpse what they had sought till then during hours and hours of labor. When this spirit of prayer prevails, real life begins, and one understands that mental prayer gives the spirit of the chant; whereas the psalmody furnishes to mental prayer the best possible food, the very word of God, distributed and explained in a suitable manner, according to the cycle of the liturgical year, according to the true time, which coincides with the single instant of immobile eternity.

A Lifting Up of the Soul Toward God

Such prayer is no longer mechanical, but organic; the soul has returned to vivify the body; prayer is no longer a succession of words; we are able to seize the vital spirit running through them. Without effort, even in the most painful hours of life, we can taste the admirable poetry of the psalms and find in them light, rest, strength, renewal of all energies. Then truly this prayer is a lifting up of the soul toward God, a lifting up that is not uniformly retarded, but rather accelerated. The soul burns therein and is consumed in a holy manner like the candles on the altar.

The Angelic Doctor Moved to Tears

St. Thomas Aquinas deeply loved this beautiful chant thus understood. It is told of him that he could not keep back his tears when, during Compline of Lent, he chanted the antiphon: “In the midst of life we are in death: whom do we seek as our helper, but Thou, O Lord, who because of our sins art rightly incensed? Holy God, strong God, holy and merciful Savior, deliver us not up to a bitter death; abandon us not in the time of our old age, when our strength will abandon us.” This beautiful antiphon begs for the grace of final perseverance, the grace of graces, that of the predestined. How it should speak to the heart of the contemplative theologian, who has made a deep study of the tracts on Providence, predestination, and grace!

The Spiritual Anemia of the Theologian

The chant, which prepares so admirably for Mass and which follows it, is one of the greatest means by which the theologian, as well as others, may rise far above reasoning to contemplation, to the simple gaze on God and to divine union. The theologian who has spent a long time over his books in a positive and speculative study of revelation, in the refutation of numerous errors and the examination of many opinions relating to the great mysteries of the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Eucharist, the life of heaven, needs, after such study, to rise above all this bookish knowledge; he needs profound recollection, truly divine light, which is superior to reasoning and gives him the spirit of the letter which he has studied. Otherwise he grows spiritually anemic and, because of insufficient contact with the light of life, he cannot give it adequately to others. His work remains too mechanical, not sufficiently organized and living, or it may be that the governing idea of his synthesis has not been drawn from a high enough source; it lacks amplitude, life, radiation, and little by little it loses its interest. The theologian needs often to find the living and splendid expression of the mysteries that he studies in the very words of God, such as the liturgy makes us taste and love: “Taste, and see that the Lord is sweet.” (3)

The word of God, which is thus daily recalled to us in prayer,is to its theological commentary what a simple circumference is to the polygon inscribed in it. We must forget the polygon momentarily in order to enjoy a little and in a holy manner the beauty of the circle, which the movement of contemplation follows, as Dionysius used to say. This is found during the chant, if mechanical haste is not substituted for the profound life which ought to spring from the fountain. The body of the chant must be truly vivified by the spirit of prayer.

Worthy Choral Prayer Attracts Good Vocations

There is great happiness in hearing the Divine Office thus chanted in many monasteries of Benedictines, Carthusians, Carmelites, Dominicans, and Franciscans. This prayer attracts good vocations, whereas the other, because it is materialized, drives them away. When we hear the great contemplative prayer in certain cloisters, we feel the current of the true life of the Church; it is its chant, both simple and splendid, which precedes and follows the sublime words of the Spouse: the Eucharistic consecration. We are made to forget all the sorrows of this world, all the more or less false complications and all the tiresome tasks imposed by human conventions. God grant that the chant may ever remain thus keenly alive day and night in our monasteries! It has been noticed that when it ceases at night in those convents where it should go on, the Lord raises up nocturnal adoration to replace it, for living prayer ought not to cease, and prayer during the night, by reason of the profound silence into which everything is plunged and for many other reasons, has special graces of contemplation: Oportet semper orare.

Holy Repose

The chant thus understood is the holy repose which souls need after all the fatigues, agitations, and complications of the world. It is rest in God, rest that is full of life, rest which from afar resembles that of God, who possesses His interminable life tota simul, in the single instant which never passes, and which at the same time measures supreme action and supreme rest, quies in bono amato.

A Cure for Pious Sentimentality

We may define the mutual relations of mental prayer and the Divine Office by saying that from mental prayer the Office receives the habit of recollection and the spirit of prayer. On the other hand, mental prayer finds in liturgical prayer an abundant source of contemplation and an objective rule against individual illusions. The Divine Office cures sentimentality by continually recalling the great truths in the very language of Scripture; it reminds presumptuous souls of the greatness and severity of divine justice, and it also reminds fearful souls of infinite mercy and the value of the passion of Christ. It makes sentimental souls live on the heights of true faith and charity, far above sensibility.

It will suffice here to recall one example among many: the tract from the Mass for Quadragesima Sunday taken from psalm 90: “He that dwelleth in the aid of the most High, shall abide under the protection of the God of Jacob. He shall say to the Lord: Thou art my protector and my refuge: my God, in Him will I trust. For He hath delivered me from the snare of the hunters and from the sharp word. He will overshadow thee with His shoulders: and under His wings thou shalt trust. His truth shall compass thee with a shield: thou shalt not be afraid of the terror of the night, of the arrow that flieth in the day. . . or of the noonday devil. A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand: but it shall not come nigh thee. . . . For He hath given His angels charge over thee to keep thee in all thy ways. In their hands they shall bear thee up lest thou dash thy foot against a stone. . . . He shall cry to Me, and I will hear him: I am with him in tribulation, I will deliver him and I will glorify him. I will fill him with length of days; and I will show him My salvation.”

All the Ages of the Spiritual Life

The liturgy recalls all the ages of the spiritual life by the joyful mysteries of the childhood of the Savior, by His passion, and by the glorious mysteries; it thus gives true spiritual joy which enlarges the heart: “I have run the way of Thy commandments, when Thou didst enlarge my heart.” It prepares the soul for the more intimate and silent prayer of meditation.