Kinship in the Cloister

Here is the talk I gave this morning in Chapter.

Ties That Bind

The presence of members of the same family in a monastery has never been without complications. The classic example is that of Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face in the Carmel of Lisieux together with her three sisters Marie, Pauline, and Celine, and her cousin Marie Guérin. Similarly, when two or more men, bound together by the ties of a close friendship in the world, enter the same monastery, while it can be a boon for the community, it can also present problems.

Everything Has Become New

In Chapter 69 of the Holy Rule, Saint Benedict warns against the nefarious effects of tribal, familial, or emotional ties in the context of monastic life. A monk’s loyalty belongs to Christ, represented by the father of the monastery, and to the new family constituted under his authority by the action of the Holy Spirit and by profession according to the Holy Rule.

Christ died for us all, so that being alive should no longer mean living with our own life, but with His life who died for us and has risen again; and therefore, henceforward, we do not think of anybody in a merely human fashion; even if we used to think of Christ in a human fashion, we do so no longer; it follows, in fact, that when a man becomes a new creature in Christ, his old life has disappeared, everything has become new about him. This, as always, is God’s doing; it is He who, through Christ, has reconciled us to Himself, and allowed us to minister this reconciliation of His to others. (2 Cor 5:16-19)

Monastic Friendship

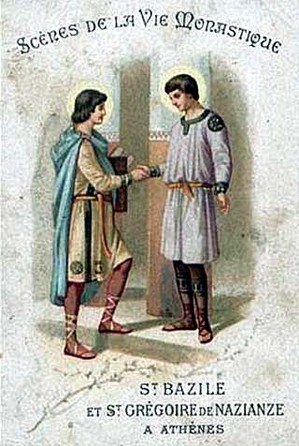

Does friendship have a place in monastic life? Surely, it does. I would recall, for example, the friendships of Saint Basil and of Saint Gregory Nazianzen, and of Saint Aelred and his biographer, Walter Daniel. Monastic friendships, however, are ordered and subordinate to the all-consuming love of Christ and to that portion of His Mystical Body that is the ecclesiola of the monastic community. Saint Gregory Nazianzen writes:

We began to feel affection for each other. When, in the course of time, we acknowledged our friendship and recognized that our ambition was a life of true wisdom, we became everything to each other: we shared the same lodging, the same table, the same desires the same goal. Our love for each other grew daily warmer and deeper.

The same hope inspired us: the pursuit of learning. This is an ambition especially subject to envy. Yet between us there was no envy. On the contrary, we made capital out of our rivalry. Our rivalry consisted, not in seeking the first place for oneself but in yielding it to the other, for we each looked on the other’s success as his own.

We seemed to be two bodies with a single spirit. Though we cannot believe those who claim that everything is contained in everything, yet you must believe that in our case each of us was in the other and with the other.

Our single object and ambition was virtue, and a life of hope in the blessings that are to come; we wanted to withdraw from this world before we departed from it. With this end in view we ordered our lives and all our actions. We followed the guidance of God’s law and spurred each other on to virtue. If it is not too boastful to say, we found in each other a standard and rule for discerning right from wrong.

The Heart of Jesus

A monastic friendship that is wholesome, pure, and fully permeable to the Holy Spirit will never constitute an obstacle to monastic discipline, to the necessary work of correction, and to the fundamental commitment to conversion of life. Such a friendship never divides the heart or closes it to growth in divine charity; it never causes inner turmoil, or jealousy. It fosters fidelity to monastic discipline, and magnanimity in the service of the brethren. A monastic friendship, rightly ordered, abides in the Heart of Jesus and, through the Heart of Jesus, contributes to the unity and fruitfulness of the monastic family in the service of the Church.