Winter Reading

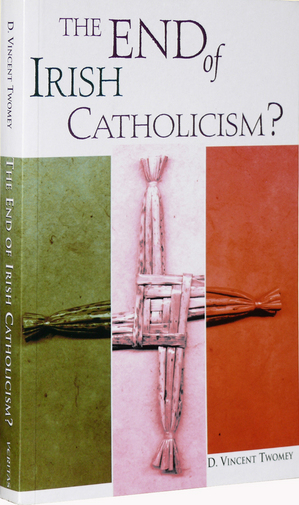

What are you reading during these dark winter days? You may think me a glutton for gloom, given recent events in the land of my forebears, but I decided that I needed to read and reflect on The End of Irish Catholicism by Father D. Vincent Twomey, S.V.D. In fact, there is nothing gloomy about Father Twomey’s book. I haven’t finished reading it yet, but what I have read of it is shot through with hope. Although written seven years ago, it remains pertinent and prophetic.

The Sacred Liturgy

Among the compelling theses of the book is Father Twomey’s conviction that the restoration of Catholic life in Ireland will be brought about, principally, through the restoration of the sacred liturgy. It takes courage to affirm this in the face of so many other pressing challenges and calls for action and reform. Father Twomey writes:

There is a need to become aware again of the importance of ritual (rubrics), namely the regular performance of the predetermined small gestures and words of infinite significance, and the rhythm of ritual movement, which is not dependent on the whim of the celebrant…. The minimalist legalistic mentality, which, it seems to me, dominated and still dominates liturgical celebration in Ireland, has even dispensed with many of the rubrics as not being absolutely essential or strictly ‘obligatory’, for example the position of hands, blessings, kneeling, pause, the use of vestments of a certain kind and colour, and so on. Indeed, ritual movement has been effectively reduced to standing at the ambo or altar or sitting on a chair. To make up for the present sterility of so much liturgical celebration, all kinds of secondary elements have been introduced as substitutes…. But we have to ask whether or not they are perhaps more a distraction from the solemnity and real beauty of the liturgy…. Do they simply entertain, or do they promote a true sense of the sursum corda?

It may seem superfluous to mention such apparently trivial things as the need for clean altar linen, chalices of artistic merit, as well as missals, lectionaries, and sacred vestments that truly worthy of the divine service. In recent times, these sacred instruments and cloths tend to made of cheap materials, and are often in poor condition, torn, unwashed. In a word, they are not exactly edifying. While the modern world is discovering the magic of candles, the Irish Church has reduced them to a minimum (usually of inferior quality, even imitation candles or a flickering electric light instead of a sanctuary lamp). The liturgy is about great events taking place by means of small gestures, where everything used takes on infinite significance. Careful attention to the details (linen, candles, vestments, etc.) expresses the celebrant’s awareness of the great mysteries for which he is responsible and conveys to others present something of the awesome presence in the Sacrament. Despite his poverty and his care for the poor (such as the orphanage he ran), the Curé of Ars procured the richest of vestments and most elaborate sacred vessels he could find in the city of Lyons for his humble, rural parish church.

Father Twomey discusses the perennial value of devotion to meet the people’s affective religious needs. He recognizes the worth of the parish-based Gaelic Athletic Association, from the ranks of which came countless fine priests. Passing in review such traditional practices as the Pattern Days (patronal festivals), penitential pilgrimages, he outlines his vision for the revitalization of a Catholicism that, long before the clerical scandals of recent years, had become a matter of dreary routine and minimalistic compliance.

Consecrated Life

Turning to the decline of consecrated life in Ireland, Father Twomey’s insights can be applied to the same problem in the United States and Canada. His remarks are nlot without relevance to certain concerns being addressed by the Apostolic Visitation of Women Religious that is underway in the United States.

The diocesan structure of various Irish-founded congregations has tended to be replaced by a national (and international) structure, with the accompanying tendency to concentrate authority on a newly established central authority, a superior-general or provincial and their councils (or ‘leadership teams’)…. The paradox is that the conscious effort within religious orders (especially of women) to try to abolish all figures of authority, now seen increasingly as one of the last vestiges of patriarchy, is accompanied by even greater institutionalization — and endless meetings.

It is evident that each religious congregation must have its own structure of authority and decision-making. Once (and, to some extent, still) the responsibility was invested in someone known personally to each member, who was elected by the community, and lived within the same community. But now it can happen that decisions affecting communities and the lives of individual religious are made by managerial-type boards (sometimes including total outsiders as experts or advisers). The decisions are those of the quasi-anonymous ‘leadership team’ — and are often the cause of considerable personal suffering to the individuals affected. Anonymous decision-making, whether within religious congregations or within the bishops’ conference, though sometimes necessary, can often be a mask behind which moral weakness and lack of real leadership take refuge. Demoralisation is the result. It is time to change.

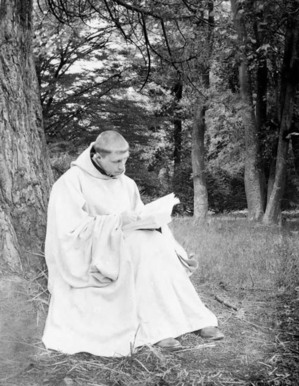

From the beginnings of the Church in Ireland, the monastic ideal set the general cultural pattern of Christianity. The renewal of the life of the modern Catholic Church will depend in the final analysis on the extent to which that monastic ideal once again ignites the imagination of the present generation.

The recovery of the various traditions of consecrated life, in particular those devoted to teaching and health care, is greatly needed to promote a genuine plurality of spiritualities and ministries within the Church. There is an urgent need for religious sisters and brothers to witness to Christ, to be the human face of the Church in the schools and in the hospital wards. All religious houses should become once again oases of prayer, personal and communal, within the desert of the modern city. The more strictly contemplative orders (male and female Cistercians, Benedictines, as well as female Dominicans, Poor Clares, Redemptorists, etc.) remain the primary witness to the unum necessarium because of the radical nature of their enclosed way of life. Such orders have often been the pioneers in the liturgical renewal. From the beginnings of the Church in Ireland, the monastic ideal set the general cultural pattern of Christianity. The renewal of the life of the modern Catholic Church will depend in the final analysis on the extent to which that monastic ideal once again ignites the imagination of the present generation.

Beyond Church and State

Father Twomey’s discussion of Church–State relations entails, necessarily, an exploration of the immutability and objectivity of natural law, morality in public life, democratic pluralism, and relativism. The following analysis is, to my mind, spot on:

…Partly in reaction to the various ideologies, which in the twentieth century caused such havoc and suffering to millions of people throughout the world, there is an understandable tendency today to shun anything that might smack of ideology, intransigeance, or the ‘imposition’ of any particular value system. The only option worth considering, it is claimed, is a pluralism not only of various cultural traditions but even a pluralism of what are misleadingly called ‘moral values’…. Morality, in the final analysis, it is claimed, is something subjective, even irrational, and thus can be reduced to personal preference or sincere ‘feelings’, which must be consigned to the private sphere (provided that they cause others no harm). Such subjective ‘feelings’, obviously cannot be ‘imposed’ on society as a whole. But moral relativism, as even secular commentators are coming to recognize more and more, is a serious threat to democracy and the moral health of the political community.

I haven’t yet finished the book, and if I continue giving copious extracts from the text, I risk violating some sort of copyright law. You don’t have to be Irish or Irish-American to benefit intellectually and spiritually from The End of Irish Catholicism. Father Twomey ends the book, however, with this anecdote, and I can’t resist ending with it here.

An tAthair Peader Ó Laoghaire in his biography Mo Scéal Féin (p. 25) tells of his own experience in bringing the Viaticum:

When I anointed one of the old people and gave him the Sacred Body and then when he would say, ‘My Lord Jesus Christ is my Love! My lasting love is He!’ my breath would catch, my heart beat faster and tears pour down from my eyes, so that I would have yo turn aside a little.

This is the ‘soul’ of the Irish Catholic tradition, the spark that kept the embers glowing in the centuries that saw the destruction of its cultural richness. May it be rekindled among us! Come, Holy Spirit…

Dear Father Mark,

You, your community and your beautiful website/blog are an inspiration. I would like very much to send you an e-mail but cannot find your address. Would you kindly send me one so I may contact you.

With prayers,

Brother Craig

monkadorer@verizon.net

http://www.monksofadoration.org