Lent and Lectio Divina

Tuesday of the First Week of Lent

Isaiah 55:10-11

Psalm 33:4-5, 6-7, 16-17, 18-19

Matthew 6:7-15

Lectio and Oratio

Today’s Mass invites us to focus on two practices necessary to the Christian life at all times, but utterly crucial during Lent: in the First Reading, lectio, and in the Gospel, oratio. In Isaiah God speaks of his descending Word, the same Word proclaimed from the ambo and heard in our solitary lectio divina. In the Gospel our Lord Jesus Christ, the Word Himself, gives us words for prayer to the Father: the very form of our common and solitary oratio.

Pope Benedict XVI on Lectio Divina

When Pope Benedict XVI addressed the young Catholics of the world in view of the World Youth Day 2006, he them to the practice of lectio divina. He even explained it for them in his letter. This is what he said:

My dear young friends, I urge you to become familiar with the Bible, and to have it at hand so that it can be your compass pointing out the road to follow. By reading it, you will learn to know Christ. Note what Saint Jerome said in this regard: “Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ” (PL 24,17; cf Dei Verbum, 25). A time-honoured way to study and savour the word of God is lectio divina which constitutes a real and veritable spiritual journey marked out in stages. After the lectio, which consists of reading and rereading a passage from Sacred Scripture and taking in the main elements, we proceed to meditatio. This is a moment of interior reflection in which the soul turns to God and tries to understand what his word is saying to us today. Then comes oratio in which we linger to talk with God directly. Finally we come to contemplatio. This helps us to keep our hearts attentive to the presence of Christ whose word is “a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts” (2 Pet 1:19). Reading, study and meditation of the Word should then flow into a life of consistent fidelity to Christ and his teachings.

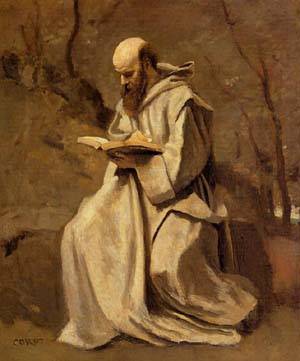

Saint Benedict

Pope Benedict XVI and Saint Benedict are, so to speak, on the same page. For Saint Benedict, Lent is the season of lectio divina par excellence. He goes so far as to rearrange the daily timetable, changing the ordered routine of things, so as to provide more time for lectio divina during Lent (cf. RB 48:14). Lent requires a change in routine; there is a healthy sense in which Lent should be upsetting. It is a time to stop doing things as we have always done them and to quicken to a more bracing rhythm of life.

Distribution of Lenten Books

The distribution of Lenten books prescribed by the Rule (RB 48:15) is a kind of Lenten sacrament. In the old monastic ceremonials each monk received his Lenten book from the hand of the abbot, kissing the book to signify not only his joy in being trusted with a precious book from the library, but also his willingness to hear the Word and be converted.

Today’s Collect

The lectionary texts are not without a connection to the Collect of the day:

Look down, O Lord, upon Thy family,

and grant that our mind,

being chastened by moderation in bodily things,

may glow with desire in Thy sight.

To Glow in the Sight of God

The Collect makes us ask that our mind, being chastened by moderation in bodily things, may glow with desire in the sight of God. Note the use of the singular “mind,” not the plural “minds.” That is significant. “Have this mind among yourselves,” says Saint Paul, which was in Christ Jesus” (Ph 2:5). Lent is not a private undertaking. Lent is corporate. This is why Saint Benedict reorders the horarium during Lent: the hours of the meals are changed. Saint Benedict is practical, concrete. He wants the whole community to feel Lent — in their bellies and in the disruption of their daily routines. Lent is something we do together, being of one mind, and something we need one another in order to do.

One Mind

We ask God that this one mind of ours — the expression of our unity in the Holy Spirit — may glow with desire. That, to me, is a fascinating image: a mind glowing with desire, pulsating with light. When we hear the term “mind” in liturgical prayers, it most often translates the Latin “mens” which means not just understanding, reason, intellect, and judgment, but also soul and spirit. It refers to all our spiritual faculties. It also refers to a shared preference, to a common focus. Try to visualize the picture today’s Collect gives us: a Church, a monastery, a community, having one single mind, and that one mind is glowing with desire for God. That is the most fundamental apostolate, the essential witness. Everything else we do is secondary.

Chastening

What do we mean when we refer to the chastening of our mind by moderation in bodily things? To chasten can mean to punish, to castigate. It also means to make chaste, that is, to refine, simplify, purify, and direct toward one thing alone, and that, I think, is the sense of the word in today’s collect. Moderation in bodily things — food, drink, sleep, talk, and entertainment — helps our minds, our spiritual faculties, to focus on the essential, on what Jesus, addressing Martha in the house of Bethany, called “the one thing necessary” (Lk 10:42). The chastened mind,”seeking first the kingdom” (Mt 6:33), “seeking the face of the Lord” (Ps 26:8-9), begins to glow with desire in the sight of God. “Let your light shine before others,” says Jesus (Mt 5:16).

Burn and Shine

The glow of holy desire requires a steady commitment to lectio and oratio. Lectio is the hearing of the Word; oratio is the Word turned into prayer. “Did not our hearts burn within us while He talked to us on the road, while He opened to us the scriptures?” (Lk 24:32). Lectio is completed by meditatio: the Word heard becomes the Word repeated and held in the mind until it begins to glow. Oratio is completed by contemplatio: the Word prayed opens the heart to a mysterious burning, to a fiery presence. Glow, then, with desire for God; burn with the fire of his presence, that the Lord may say of us what He said of John the Baptist: “He was a burning and shining lamp” (Jn 5:35).